This guide was originally published on June 19, 2019 in NYT Parenting.

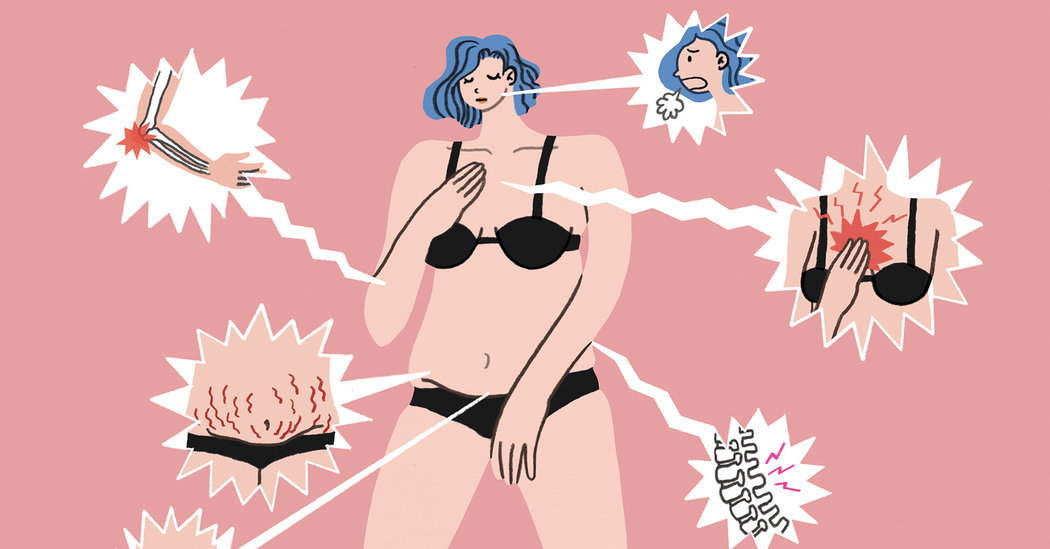

When I was pregnant, I read four books on pregnancy and two on childbirth. I read no books on what my body would be like during the first year postpartum, because I had never heard of any. During that first year, many people are underinformed about their own bodies, even as they learn vast amounts about their babies. Many of us are cleared for sex and exercise at six weeks postpartum, but a body that grew another human can take much longer than that to heal — and can be permanently changed in some ways.

For this piece, I discussed health in the first postpartum year with two ob-gyns, a nurse, two physical therapists who specialize in treating postpartum bodies and two mothers. All the experts said many people have questions about what is normal, and they recommended calling your obstetrician, midwife or primary care provider if you’re concerned about something specific. For many symptoms, a next step will be a referral to a physical therapist. The experts stressed that you don’t have to live with pain, discomfort or leaking urine, and that your health is as important as your baby’s.

Postpartum depression and anxiety are part of overall health but merit their own space, so see our guides for those topics.

Don’t ignore concerning changes.

Peeing a little when you sneeze, laugh or exercise is such a classic postpartum symptom that many assume it can’t be fixed. Not so. It’s called stress incontinence, and it’s a symptom of a problem with your pelvic floor, a set of muscles that stretch, bowl-shaped, between the tailbone and the pubic bone. Urge incontinence, in which you feel the need to urinate very frequently, feel you have a very small bladder or feel you can’t hold it, is also due to pelvic floor muscle stress.

If you have any kind of incontinence, a good first step is a referral to a physical therapist who specializes in pelvic floor issues. “Being pregnant puts stress on your pelvic muscles” because of the weight of the fetus, said Dr. Tamika Auguste, an ob-gyn at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, D.C. Vaginal delivery or a C-section can further stress your pelvic floor, especially if the C-section was unplanned and occurred after some amount of labor. “Oftentimes women don’t always recognize immediately how much of a toll that still took on their vaginal canal and pelvic floor,” said Alison Colussi, D.P.T., a physical therapist specializing in pelvic health. Muscles that stretch during delivery can either remain too loose or over-tighten in response.

Do pelvic floor exercises — but not just Kegels.

When you think pelvic floor, you probably think Kegel exercises — in which you contract your pelvic floor muscles. But Kegels are not always helpful, and they’re hard to learn how to do properly on your own, Colussi said, so it’s best to visit a physical therapist if possible. Some women’s pelvic floors are overly tight, “in a constant state of mini-Kegel,” as Colussi puts it, which Kegels would only exacerbate. Even when pelvic floor muscles are weak and need strengthening, “the focus is much more on finding the full range of motion of those muscles, which includes both relax and contract,” Colussi said.

The relaxing part is hard. I tried to do it while on the phone with Colussi. “I’m not entirely sure if they’re relaxed or not,” I told her. “Am I actually trying to contract something accidentally?” She laughed. “I hear that 10,000 times a day,” she said.

Often, Colussi said, patients come in looking for an exercise to do for 10 minutes every day. “But the question is not what’s a good exercise,” she said. It’s more about how people move in every one of their daily activities, from getting out of bed to picking up mashed fruit off the floor to lifting babies out of their cribs. The proper way to pick up that mashed fruit or a baby in a car seat is to squat down, keeping your center of gravity over your hips and not tilting forward. Then exhale, engage your abs and straighten up using your leg muscles, not your back.

Don’t put up with painful sex.

It’s common to feel discomfort or pain the first few times you have penetrative sex after childbirth, but after that, don’t put up with it. The first step is of course to go slowly and be gentle with yourself. Often ob-gyns will advise using an over-the-counter lubrication product, because breastfeeding suppresses estrogen production, and estrogen produces lubrication, explained Dr. Alison Stuebe, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology and chair of the taskforce that wrote the newest American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines for postpartum care. But lube is just a beginning, our experts all agreed.

In addition to dryness, pain during sex can be caused by pelvic floor dysfunction, other tight or stretched muscles or scar pain from a tear or episiotomy during a vaginal birth. Sex can hurt for patients who’ve had C-sections as well, because both C-sections and the process of pregnancy can stretch or tighten muscles. Ask your obstetric care provider for a referral to pelvic floor physical therapy.

Dr. Stuebe also directs patients to “The Parents’ Guide to Doing It,” an episode of “The Longest Shortest Time” podcast with sex advice columnist Dan Savage as a guest. Savage discusses types of sex other than penetration. Unfortunately, some women experience pain with any kind of sex, usually from increased nerve sensitivity, said Colussi.

Seek help if you feel pressure in your vagina.

Some women come to Colussi saying they feel pressure in their vagina, like something is obstructing their bowel movements, “or like a dry tampon is half falling out of me,” she said. Sensations like these could mean a pelvic organ prolapse, when an organ (uterus, bladder or urethra) shifts from its original position or presses against the vaginal wall. “Prolapse is probably the thing women are least prepared for,” said Colussi.

Severe prolapses can be fixed with surgery or alleviated with a pessary (a support in the vagina to prop up the prolapsing organ), but milder prolapses can be managed just by lying down more frequently and avoiding high levels of pressure in your abdomen, Colussi said. “Oftentimes for a woman it feels a lot worse than it actually is,” she said, but in other cases prolapse can be more severe than it feels, so it makes sense to see a health care provider. To better manage pressure levels in your abdomen, don’t bear down when pooping; and exhale instead of inhaling or holding your breath when you exert yourself. If you find yourself grunting and then holding your breath when you lift something heavy, try exhaling instead.

Ask your doctor about scar pain.

If you feel pain in your C-section scar or scar from a tear or episiotomy, see your medical provider. A doctor may recommend scar massage or scar mobility treatments from a postpartum physical therapist. However, be aware, scientific data on the effectiveness of scar massage is limited because it has barely been studied, Dr. Stuebe said. A 2011 paper concluded that scar massage is “anecdotally effective” but found that surgical scar massage of any kind had only been studied in a tiny sample size of 30 patients. Scar pain is common. A year after giving birth, a study found, 18 percent of women who had C-sections still had pain at the incision site, and 10 percent of women who had vaginal births still felt pain in the vagina or perineum (the area between the vagina and the anus).

Learn to carry your baby on both sides.

Carrying a baby, lifting a baby and holding a baby while breastfeeding are hard physical work, especially for women who were pregnant. Your posture and movement habits change during pregnancy from carrying around extra weight in new places, and your body also produces the hormones relaxin and progesterone, which loosen your ligaments and joints.

Baby product design doesn’t help. “Car seats and cribs have changed drastically” in recent years, said Colussi. They’re carefully designed for infant safety, but not for parent ergonomic safety. Infant or “bucket” car seats are heavy, and usually parents carry them in their nondominant arm, causing muscle imbalances. She recommends that parents practice early and often carrying their babies on both sides equally. “Cribs are hard because the rails can’t go up and down anymore,” she said. Colussi recommends that parents, especially shorter ones, place a step aerobics stepper next to the crib.

If pain persists after making these changes, physical therapy is a good idea.

Use proper form for sitting up.

If you feel a gap in your abdominal muscles, you may have diastasis recti, in which all the layers of the abdominal muscles, the rectus abdominus, separate in the middle. This happens normally during the latter part of pregnancy to make room for the growing uterus, but if it persists at your six-week postpartum checkup, ask your provider, who may refer you to a physical therapist. To avoid putting too much pressure on these muscles, avoid crunches or sit-ups, and when you sit up, don’t sit straight up using just your abdominal muscles: Roll onto your side first and use your arms.

When to Worry

-

If you have shortness of breath, pain in your chest or seizures, call 911.

-

If you have an incision that does not heal, a temperature above 100.4F, too much bleeding (soaking one pad per hour or a blood clot the size of an egg or larger), a red or swollen leg that feels painful or hot, or a headache that does not get better with medication or is accompanied by vision changes, call your medical provider.

-

If you had gestational diabetes, make sure you get screened for diabetes according to your medical provider’s advice.

-

If you had high blood pressure (pre-eclampsia) during pregnancy, make sure your blood pressure is monitored according to your medical provider’s advice. (You are still at risk for pre-eclampsia up to six weeks postpartum.)

-

If you quit or tapered smoking or other drugs during pregnancy, see your medical provider for a postpartum support plan. The stresses of life with a baby can lead to relapse.

Anna Nowogrodzki is a science journalist and mom in the Boston area.