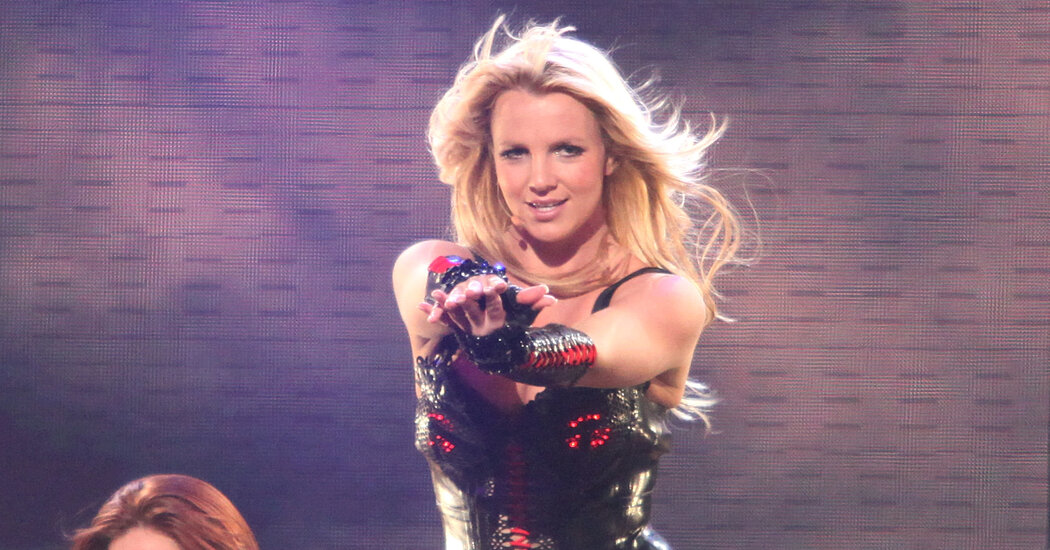

Before, during and now after the conservatorship that oversaw her life for 13 years, the pop star has used dance to assert her power and connect with her audience.

When Britney Spears spoke out in June during a hearing in Los Angeles Superior Court, she talked about how those in charge of her conservatorship had strictly governed her life for 13 years, calling the arrangement “abusive.” But she also emphasized one way she had held on to some control.

She kept on dancing.

She “actually did most of the choreography,” she said, referring to 2018 rehearsals for her later scuttled “Britney: Domination” residency in Las Vegas, “meaning I taught my dancers my new choreography myself.”

There was “tons of video” of these rehearsals online, she said, adding: “I wasn’t good — I was great.”

It was a powerful way of reminding those listening of the confidence she conveyed as a performer throughout her career. Onstage, Spears maintained control over her body, otherwise the subject of constant scrutiny — about her virginity, her weight, her wardrobe. Through movement, she conjured a world of her own making in which she really was the boss.

With her expansive arm gestures, rapid-fire turns and abdominal dexterity, Spears has always used dance to communicate her strength. Brian Friedman, the choreographer responsible for some of Spears’s most famous routines, noted that there was a visible change in her approach to dancing after the conservatorship was put in place in 2008.

“I feel like that was her way of being able to be in control of something, because she didn’t have control over so much,” Friedman said in a phone interview. “So by being able to step into the studio and say ‘I don’t want to do this, I want to do this, I’m going to make up my own thing,’ it gave her some kind of power.”

When Spears announced “an indefinite work hiatus” in early 2019, she began posting videos of herself dancing to Instagram. Most of these clips show her twirling alone, in a loose, visibly improvised style, on the marble floor of her California home.

In the videos, she looks straight at the camera, breaking her gaze only for the occasional turn, or to flip her hair. This isn’t the movement of the practiced stage performer and pop star; it’s more exploratory, as if she were searching for the right step or feeling instead of trying to nail it.

Under the conservatorship, Spears’s videos became the subject of debate and speculation. While some fans cheered her on, others were bothered by her lack of polish and level stare. “Does anyone ever feel awkward or uncomfortable watching this?” someone asked in the comments of a post in February.

For Spears, though, the point was simple. It’s about “finding my love for dancing again,” she wrote in a March post. In others, she said that she moves like this for up to three hours a day, taping her feet to avoid getting blisters.

For dancers and choreographers who have worked with Spears, her Instagram’s focus on dance made sense. “In a period of time when she did not have freedom, that gave her freedom,” Friedman said.

Sharing her improvised dance sessions also allowed her to connect directly with fans. Brooke Lipton, who danced with Spears from 2001 to 2008, said in a phone interview that Spears’s “dancing told the world she needed help — without saying anything, because she couldn’t.”

If Spears can still show off the occasional fouetté turns, in which she spins on one leg, it’s because of a lifetime training in the dance studio. Lipton, Friedman and others say that Spears matched the range and commitment of professional dancers, with a preternatural knack for picking up choreography on the fly.

“She grew up dancing,” said Tania Baron, who started performing at shopping malls with the budding star in 1998. “There are artists who dance certain parts of a show. There are artists who are just natural movers. Then you’ve got people like Britney, who can really dance just like her dancers.”

Spears’s care and attention to how she presented herself in movement speak to how she understood her body as a dancer does — as an artistic instrument. Top-level choreographers might have been creating dances for her, but they were also working for other pop stars. The difference, Elizabeth Bergman, a scholar of commercial dance, said in a phone interview, is “the way she’s doing them.”

In the years before the conservatorship, Spears carefully chose the choreographers she worked with. Valerie Moise, also known as Raistalla, who danced in Spears’s concerts and videos in 2008 and 2009, points out that these collaborations contributed to the longstanding popularity of jazz funk, known for its defiant, hard-hitting moves.

“This is a style that is almost like a culture to her,” Moise said in a phone interview. “It accentuates how she wants to express herself.”

And Spears did something more than just continue in the tradition of the pop artists who danced before her.

“Of course there was Madonna, and Michael and Janet, and they were fantastic,” Lipton said. “But dance was also evolving at a time when Wade and Brian were stepping up the expectations of what dancers could do,” she added, referring to Spears’s frequent choreographers, Wade Robson and Friedman. Their routines were faster than those of the previous generation, with more movement and action per beat. “Every count was being filled,” Lipton said.

When learning routines from choreographers, Spears would speak up when they included steps that did not feel right on her body, sometimes suggesting her own moves instead. “She was very much the boss,” Baron said about Spears at the beginning of her career. “Not in a mean way. But if she didn’t like something, she would make it known.”

From an early age, Spears recognized dance as a medium in which presence and artistry can’t be faked. “When you’re dancing, you just can’t do a step, you’ve got to get into it,” she said when she was a 12-year-old star of “The Mickey Mouse Club.”

Randy Connor, who choreographed Spears’s routine in the classic “ … Baby One More Time” video, said he believed her ability to convey her feelings with and through her body was a major part of her initial star appeal. “It resonated with so many people because of her conviction in the movement,” he said in a phone interview.

Coming up in an industry known for its artifice, Spears used dance as a means of transparency with fans. Everyone knows there is no such thing as dance-syncing.

“That was truly how she communicated as an artist,” Friedman said. Even before the start of Spears’s conservatorship, he added, “she couldn’t really say everything she wanted in public, in interviews. But when she danced, it was unapologetic.”

Spears’s songs became coming-of-age and coming-out anthems, and learning her moves enabled fans to explore aspects of their identities with the same boldness she projected with her body. Imitating her performances allowed them to “feel the spirit of Britney,” as Jack says on the TV show “Will & Grace,” after doing the shoulder lifts and arm pumps that are part of the routine to “Oops! … I Did It Again.”

Lipton emphasizes that Spears chose her steps so that anyone watching could move along with her.

“She would do the choreography just a little bit less,” Lipton said. “In a moment where we’re doing all of these turns and slams, she just smiles and points her fingers out, before joining back in. It wasn’t unattainable.”

If Spears embraced her strength in movement along with her fans, many commentators did not, often describing her dancing as if it were a ploy used to compensate for lack of talent. Other young female pop stars like Jessica Simpson and Avril Lavigne boasted about not dancing, as if this made them more authentic artists. In 2002, The Associated Press identified a crop of “Anti-Britneys” who supposedly challenged the idea that you have to “cavort in tight clothes to be sexy and successful in pop music.”

Friedman says that Spears’s dancing was about her artistry, not manufactured sex appeal.

“As Britney’s choreographer for many years, I never set out to make movements to pleasure anyone else,” he said. “It was about how I could make her feel empowered in her body.”

In the 2008 documentary “Britney: For the Record,” filmed in the early days of the conservatorship, Spears speaks as if already aware of how important dance would become for her under the control of others.

“Dancing is a huge part of me and who I am. It’s like something that my spirit just has to do,” she says. “I’d be dead without dancing.”

Arguing for the conservatorship’s termination 13 years later, she identified one of her breaking points as the moment when she was refused the right even to this control over her body. Spears said that at a dance rehearsal in early 2019, after saying that she wanted to modify a step in the choreography, she was informed that she was not cooperating.

She declared her response firmly in court: “I can say no to a dance move.”