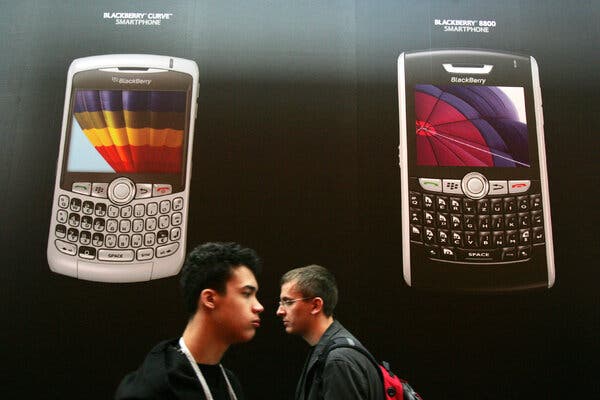

BlackBerry was once Canada’s most valuable company and a global force in tech. The final step in its downfall as a phone maker arrived this week.

For many years, my work for The New York Times was centered on one thing: BlackBerrys. But this week, the onetime wonder of Canada’s tech industry finally faded out as a smartphone maker.

There was a time when interruptions to BlackBerry service were big news at The Times and at other news organizations around the world. But the company’s decision, which took effect Tuesday, to permanently shut down BlackBerry email, BlackBerry Messenger and other services needed to operate most of its phones passed by with much less notice.

[Read: BlackBerry Ends Service on Its Once-Ubiquitous Mobile Devices]

In all, I’ve written more than 300 articles about BlackBerry devices and Research in Motion, as the phone maker was long named. While I never owned a BlackBerry, out of stinginess more than anything else, I did borrow one occasionally.

My first BlackBerry article for The Times, published in January 1999, offered little suggestion that the device would turn Research in Motion into Canada’s most valuable corporation and ultimately develop an almost cultish following among users. It was the second-to-last item in a long list appearing in Circuits, The Times’s former weekly technology section, and it described an “E-mail-ready pager” that was roughly the shape of a credit card and ran off a single AA battery. (While its functions were limited, adjusted for inflation, the original version of the BlackBerry cost roughly $650.)

I took one of those original BlackBerrys cross-country skiing and sent an email from a cabin along the trails just for the sheer novelty of it. Now, of course, I’m happiest skiing where there’s no signal that allows emails, texts and Slack messages to follow me.

What I didn’t foresee was how important the BlackBerry’s physical keyboard would be to its success, as well as to how it would be used: “The pager’s itty-bitty keyboard, however, will discourage long-winded messaging,” I wrote.

In the device’s early years, when BlackBerrys were overwhelmingly bought by corporations and government agencies, RIM’s executives clearly catered to the information technology department heads who approved the purchase of the phones en masse, not the phone users themselves. In a time when there was far more anxiety about email security in general, I.T. bosses had to be persuaded that wireless emails could be kept safe from hackers’ eyes. More than anything, BlackBerry was selling the idea that the unique network its devices operated through provided absolute security.

And that security went beyond email and messaging. Early on, Mike Lazaridis, the co-founder of RIM and the driving force behind the company’s technology, boasted to me that there were no cameras on BlackBerrys because corporate and government security users didn’t want them.

BlackBerrys, of course, grew in size and gained features like the ability to make phone calls and, eventually, take photos. And then, almost overnight, they became a hot consumer product and RIM became an industry giant. The company, however, would struggle with the much more fickle consumer market. Its lower priced handsets for consumers, very unlike the ones with which it made its name, were often buggy and unreliable.

As RIM struggled to figure out what consumers wanted, it tried a something-for-everybody approach. In 2011, the company was unable to tell me how many different models it offered for an article in which I described its lineup this way: “There are BlackBerrys that flip, BlackBerrys that slide, BlackBerrys with touch screens, BlackBerrys with touch screens and keyboards, BlackBerrys with full keyboards, BlackBerrys with compact keyboards, high-end BlackBerrys and low-priced models.” In RIM’s efforts to cater to everyone, it gradually attracted almost no one.

By 2011 of course, the iPhone was well established. RIM’s executives were initially dismissive of Apple’s offering. It lacked, of course, a physical keyboard. Shortly after the iPhone was released, one senior RIM executive brought up at the end of an interview what he saw as the iPhone’s fatal flaw. Unlike BlackBerrys, he noted, iPhones couldn’t lower wireless data costs by compressing web pages. They were, he declared, “bandwidth inefficient.”

Assuming that they knew anything about bandwidth efficiency, consumers didn’t really care. Smartphones had become all about software, not keyboards — a fact BlackBerry’s executives were slow to accept. “They are not idiots, but they’ve behaved like idiots,” Jean-Louis Gassée, a former Apple executive, told me in 2011.

BlackBerry did finally wake up, but it was too late. The BlackBerry 10 operating system, the company’s response to the iPhone and Google’s Android, was so troubled by delays and development problems that it led to the departure of Mr. Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie, the company’s co-chief executives. When phones using the new operating system finally arrived, they were met with waves of indifference.

BlackBerry the company staggers on, however. It lost $1.1 billion during its most recent fiscal year. Now out of the phone business, it’s selling security software and software systems for carmakers. It has licensed the BlackBerry name to Asian phone makers who have produced some Android-based models. (Those phones continue to work.)

I asked BlackBerry how many users of its older phones were affected by this week’s shutdown. It didn’t respond.

Trans Canada

-

The federal government reached what it called the largest settlement in Canada’s history this week after agreeing to provide 40 billion Canadian dollars in a mixture of compensation and funding to repair the nation’s discriminatory child welfare system, Catherine Porter and Vjosa Isai report.

-

The changes to Canadian law that make conversion therapy a crime went into effect Friday. Christine Hauser goes through the history of the legislation and explains the consequences of the move.

-

Brian Hamilton, an assistant equipment manager for the Vancouver Canucks, learned that he had a cancerous mole on his neck through an unlikely channel: a message typed on a phone by a fan and held against the glass during a game in Seattle. Eduardo Medina reports that months later, Mr. Hamilton finally met the sharp-eyed Nadia Popovici.

-

My Montreal-based colleague Dan Bilefsky looks back at his international travel experiences during year two of the pandemic.

-

Joe Morena, of St-Viateur Bagel in Montreal, discussed his unusual line of business with The Times for an illustrated feature.

-

A bitter disenrollment drive by the Nooksack Indian Tribe in northern Washington State has left dozens of people descended from a First Nation in Canada facing eviction, Mike Baker reports. The outcast Nooksack members are petitioning the U.S. government to intervene.

-

It’s Canada’s most notorious holiday party. Politicians, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, have condemned a group that flouted Covid-19 and air safety rules by partying on a chartered flight from Montreal to Mexico. Now many members of the group are being shunned by airlines as they attempt to return home and could face substantial fines following an investigation by Transport Canada.

A native of Windsor, Ontario, Ian Austen was educated in Toronto, lives in Ottawa and has reported about Canada for The New York Times for the past 16 years. Follow him on Twitter at @ianrausten.

How are we doing?

We’re eager to have your thoughts about this newsletter and events in Canada in general. Please send them to nytcanada@nytimes.com.

Like this email?

Forward it to your friends, and let them know they can sign up here.