What’s worse than an anti-vaxxer in a pandemic? An anti-vaccine star athlete. That paragon of physical health, cloaked in a cape of defiance, declares to the world by example that you don’t have to follow public health policy after all — as long as you win.

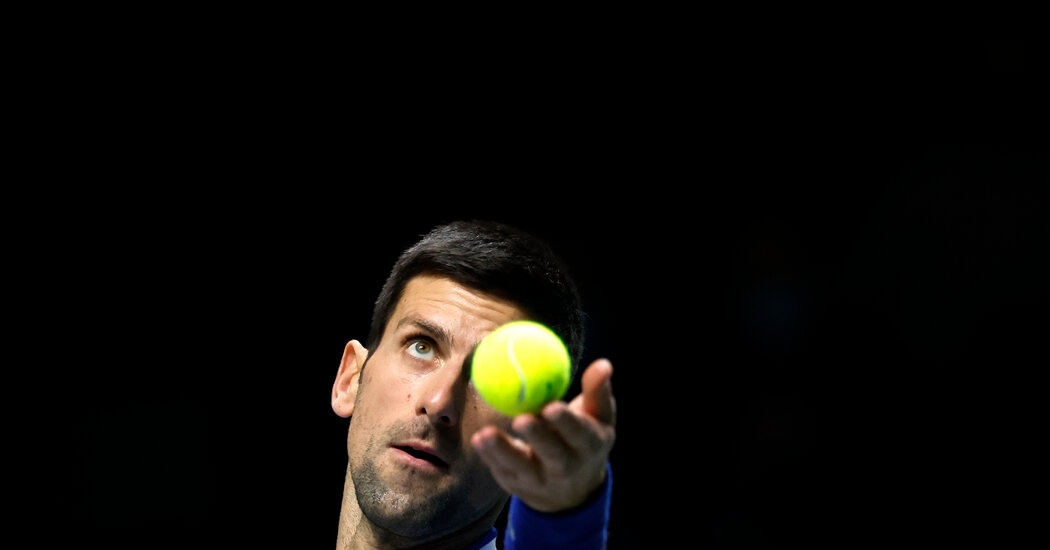

Which brings us to the top-ranked male tennis player in the world, Novak Djokovic. The sport’s most visible vaccine skeptic, at the start of the pandemic Djokovic said he “wouldn’t want to be forced by someone to take a vaccine,” and expressed curiosity about “how we can empower our metabolism to be in the best shape to defend against impostors like Covid-19.” This week Djokovic obtained a medical exemption from tournament organizers for a visa to compete in the Australian Open without being vaccinated. He flew to Melbourne via Dubai.

Meanwhile, Australia is dealing with a serious Omicron surge. Victoria state, where the Open is held, recorded almost 22,000 new cases on Wednesday, when Djokovic arrived. It was the largest daily jump in cases of the pandemic.

After a 10-hour standoff at the airport, Australian border authorities denied Djokovic’s visa. (His lawyers said he tested positive for the coronavirus in mid-December, meeting Australia’s conditions for exemption.)

What’s unfolding in Australia is a dramatic example of disputes we’re seeing play out around the world, in sports and beyond, as institutions weigh public health guidelines against their own needs. Even as the coronavirus surges again, and so does public exhaustion with lockdowns and school closings, sports bodies are compelled to accommodate problematic athlete behavior. They need their biggest talents — and the ticket sales, broadcast viewership, advertising deals and attention that celebrities bring.

Athletes have more independent agency than ever, and via social media they have their own huge platforms to express their views directly to fans. This has enabled some athletes to become powerful advocates for social justice, and others to use their fame to advance more questionable positions. Lately, several have used their platforms to amplify anti-science beliefs to an already mistrustful public.

The Djokovic saga is exposing an uncomfortable truth for sports institutions: They are only as good as their stars. And the stars are calling the shots.

It’s an issue that has arisen in sports many times lately. Notably, Naomi Osaka defied the organizers of the French Open, declining to do post-match news conferences to protect her mental health. She paid for her choice, first in the requisite fines and ultimately by withdrawing altogether from the tournament, but many praised her for her stance. For Osaka, the power of her personal brand allowed her to safeguard her health. For anti-vaccine athletes, however, stardom can give them leeway to flout sensible public health precautions, and act as a champion for others who do the same.

“Confronted with this latest virus surge, both the N.B.A. and the N.F.L. have essentially waved the white flag,” wrote Jamele Hill in The Atlantic last week, before the latest unvaccinated player controversy, explaining how leagues are giving in to fans’ desires and letting unvaccinated players compete. She continued: “Now the leagues are choosing instead to cede to the forces of capitalism.”

She’s right. In the N.B.A., the Brooklyn Nets have capitulated and allowed Kyrie Irving, a seven-time All-Star, to play part time in away games, the only ones he is legally permitted to play because of his decision to remain unvaccinated. (Players in indoor arenas in New York City must be vaccinated.)

In the N.F.L., the Green Bay Packers starting quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who is also the league’s current Most Valuable Player, is vocally anti-vaccine and allowed to play regardless. After he tested positive for the virus in November, Rodgers went on the Pat McAfee Show to explain his views to its audience of 1.6 million.

“I believe strongly in bodily autonomy and the ability to make choices for your body,” Rodgers said, “not to have to acquiesce to some sort of woke culture or crazed individuals who say you have to do something.”

Athletes have been scorned by some for these views. Meanwhile they got more attention, won more games. That expanded their platform for promoting widely discredited science. Many of these athletes’ fans have rallied to express their support for the stars they identify with.

The conversation is as much about fairness as it is about public health. Why should a player get a free pass when other players, and the fans keeping them in business, have to be vaccinated and abide by travel restrictions? Workplaces around the world are filled with Djokovics, difficult but valued or essential employees who expect special accommodations in order to come to work — even when the accommodations they seek are grounded in anti-science views that might put their colleagues at risk.

When it comes to athletes, what they do in public health situations matters even more. Beyond the social influence that comes with their platforms, star athletes are symbols of good health, success and leadership — that’s why they’re sought after as the public face of performance apparel and shoe companies, breakfast cereals and countless other brands.

And that’s why it’s disappointing to see sports bodies fail to exert the one lever of control that they retain: whether or not athletes are allowed to compete.

The Australian Open has had reason to want to salvage this year’s tournament, amid the grimness of another Covid surge. It has already lost Roger Federer, who is recovering from knee surgery. Naomi Osaka is planning to play, but neither Serena nor Venus Williams will attend, for the first time since 1997.

The Australian Border Force did what sports bodies are failing to do: say no. If athletes don’t like restrictions imposed on the unvaccinated, they could just get a shot like millions of other people — a privilege that millions more are still waiting for.

Now Djokovic has appealed, and is being held in a hotel over the weekend in Australia. In this way he’s no different than the rest of us: stuck in place, awaiting his fate.

Lindsay Crouse is a writer and producer in Opinion who writes on gender, ambition and power.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.