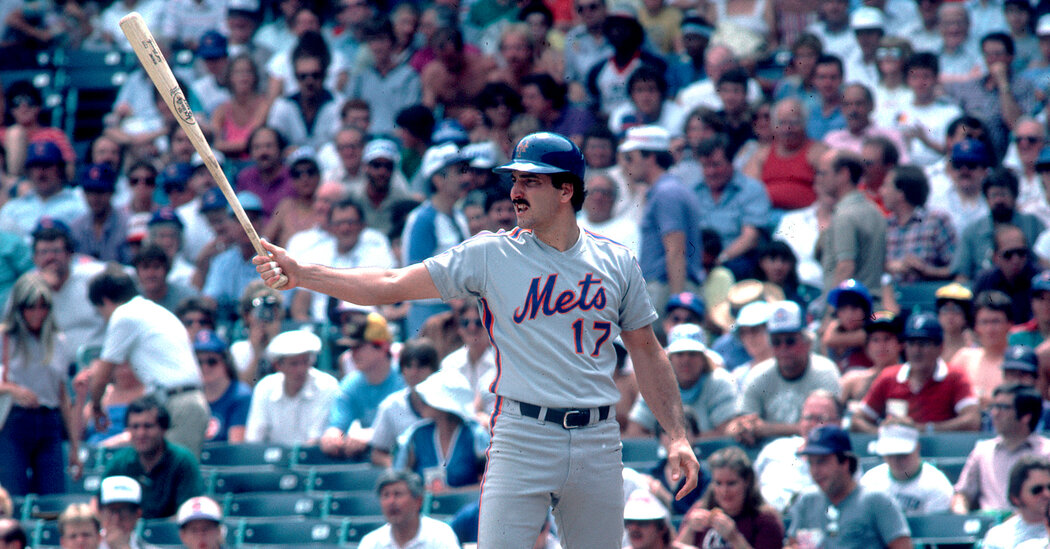

The retirement of Keith Hernandez’s No. 17 continues a recent trend of recognizing the players most crucial to the team’s glory years.

It’s a feel thing, the notion of retiring a player’s number, as the Mets will now do for Keith Hernandez’s No. 17. It is more about symbolism than statistics, a referendum on the meaning of a player to a team and a town.

Many teams have long understood this. There is no plaque in Cooperstown, N.Y., for Thurman Munson, but the Yankees retired his No. 15 anyway. Same with Johnny Pesky and the Boston Red Sox, Frank White and the Kansas City Royals, Randy Jones and the San Diego Padres and on and on and on.

The Mets took a long time to grasp the concept. It took them until their 55th season, in 2016, to retire a second player’s number. That was because Mike Piazza had just been elected to the Hall of Fame, meaning his No. 31 could join Tom Seaver’s No. 41 on the facing of the top deck in the left field corner at Citi Field.

The Mets had also retired the numbers of managers Casey Stengel (37) and Gil Hodges (14), and Jackie Robinson’s 42 is retired throughout Major League Baseball. But the team was notoriously stingy in recognizing players; even Gary Carter, the Hall of Fame catcher whose No. 8 has been out of use since 2001, was not honored with a number retirement before his death in 2012, a cruel and pointless oversight.

Hernandez, 68, is still here. You can find him on SNY broadcasts and Twitter and “Seinfeld” reruns on Netflix. After a ceremony on July 9, you will also find him in a lineup with other essential Mets players: Seaver, Piazza and Jerry Koosman, whose No. 36 was retired last year. No Met has worn No. 17 since Fernando Tatis Sr. in 2010, and now it belongs to Hernandez forever.

“He brought a winning culture, just the way he moved and the way he acted and the way he played,” said Ron Darling, Hernandez’s teammate on the field and in the broadcast booth, adding later, “I didn’t know the game could be played that correctly.”

In his 20s, with the St. Louis Cardinals, Hernandez achieved nearly everything a player could hope to do: a World Series title, a Most Valuable Player Award, a Silver Slugger, two All-Star selections and five Gold Gloves at first base.

He also used cocaine, clashed with Manager Whitey Herzog, and got traded in June 1983 to baseball oblivion: the last-place Mets, for the giveaway price of pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey.

“I remember Dave Kingman meeting me in the clubhouse — Dave Kingman, who was so deadpan, never any emotion, straight face, I never saw him smile,” Hernandez said. “He had a big smile on his face to greet me and shake my hand, and he said, ‘Thank gosh you’re here, because you’re my ticket out of here.’”

The Mets had been in a spiral since trading Seaver in 1977, but by 1983 he was back for a second stint. Things had gotten loopy for the franchise and The Franchise.

“Seaver comes up to me and says, ‘Welcome to the Stems,’” Hernandez said. “I go, ‘Stems?’ He goes, ‘Mets spelled backwards!’ I went, ‘Where am I?’ I left a team in first place, was a defending world champion, and I’m going, ‘Oh my gosh.’

“I get on the bus after the ballgame to go back to the hotel, there’s no one on the bus. I go into the hotel bar after the game, there’s no one in the hotel bar. I went, ‘Oh, boy.’ So I had three months to really soak it all in.”

The Mets finished the 1983 season 68-94, worst in the National League. Hernandez, a California native, considered signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers or the San Diego Padres. His father, John, persuaded him to stay in New York, reminding him of the Mets’ loaded farm system. After seven losing seasons in a row, the Mets would have the majors’ best record (575-395) during Hernandez’s six full seasons in Flushing.

Hernandez prepared himself with mental and physical changes before his first spring training with the Mets. Newly separated from his wife, he spent the winter in Philadelphia at the suggestion of a friend, Gary Matthews, who had just finished the season with the Phillies. Matthews liked to run for exercise, and while Hernandez had never trained much in the off-season, he took to Matthews’s program, running along the Schuylkill River, past Boathouse Row, down to the Art Museum. He reported to camp in peak condition, ready to embrace a new role for his 30s: wizened clubhouse leader and debonair man about town.

Hernandez, who had stopped using cocaine just before the trade, found a mentor in Rusty Staub, the veteran pinch-hitter. Staub encouraged Hernandez to live in Manhattan, on the East Side, in Turtle Bay. Hernandez took to his surroundings, on and off the field, and was the runner-up for M.V.P. The Mets became contenders, then added Carter for the 1985 season and won the World Series in 1986.

To do it, they first had to outlast the Houston Astros in a tense National League Championship Series. Before the final out, in the 16th inning of Game 6 at the frenzied Astrodome, Hernandez met with Carter and Jesse Orosco on the mound. Orosco had given up a homer off a fastball in the 14th, and a homer by Kevin Bass would lose the game. Hernandez told Orosco he would kill him if he threw Bass a fastball.

Orosco threw all sliders and struck out Bass to win the pennant. Such was the gravitas of Hernandez.

“I was trying to think of the history of New York sports, and I think of Keith a little bit like I think of Mark Messier — a world champion with another organization, an M.V.P. player, a guy that, once he wore a New York uniform, brought instant credibility,” Darling said. “And that’s what Keith was for our ’86 players.”

Hernandez won six Gold Gloves with the Mets, with a .387 on-base percentage and 80 home runs. His .297 average ranks second in club history to John Olerud’s .315 among players with at least 1,500 plate appearances. The Hall of Fame has eluded Hernandez, but he would seem to have a chance in the next few years.

Hernandez had more wins above replacement (60.3) than Harold Baines, Lee Smith, Jim Kaat, Tony Oliva, Minnie Miñoso and Hodges, who have all been elected by committees in the last four years. He did not have the power of Eddie Murray or Tony Perez or other star first basemen of his era. But he would not look out of place in Cooperstown.

“Hopefully I’ve got another, what 15, 16, 17, 18 years of life?” Hernandez said. “Maybe it’ll happen before I kick the bucket.”

The Mets and their owner, Steven Cohen, did not wait for a committee to validate Hernandez’s legacy. They understand — finally — that they are stewards of their past, and Hernandez is vital to their story.