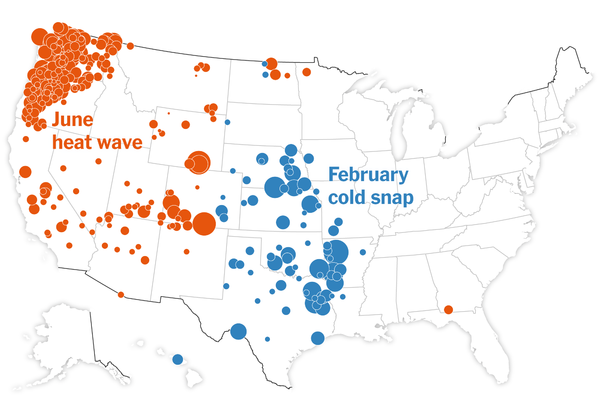

The Times analyzed temperature data from weather stations across the United States. The result: 2021 was a huge year for records, both high and low.

We’re also covering air pollution, movies and skiing.

Krishna Karra and

Temperatures in the United States last year set more heat and cold records than any other year since 1994, according to a New York Times analysis of weather station data.

The Times analyzed temperature data from more than 7,800 weather stations across the United States. Records have been set somewhere in the country every year since at least 1970, but 2021 stands alone when compared with recent years.

Heat waves made up most of these records. New highs were reached last year at 8.3 percent of all weather stations across the nation, more than in any year since at least 1948, when weather observations were first digitally recorded by the U.S. government.

Why it matters: Extreme temperature events often demonstrate the most visible effects of climate change.

Quotable: “We do not live in a stable climate now,” said Robert Rohde, the lead scientist at Berkeley Earth. “We will expect to see more extremes and more all-time records being set.”

You can read our article, and see the full set of maps and charts, here.

More important numbers from the past week:

-

U.S. greenhouse gas emissions bounced back last year. Emissions rose 6 percent in 2021 after a record 10 percent decline in 2020, fueled by a rise in coal power and truck traffic as the U.S. economy rebounded from the pandemic.

-

2021 was Earth’s fifth-hottest year. The finding, by European researchers, fits a clear warming trend: The seven hottest years on record have been the past seven.

-

The oceans set another record for heat content last year, according to a new analysis. The oceans take up about 93 percent of the excess heat resulting from greenhouse gas emissions. For more on oceans’ effects on climate, explore articles on the Gulf Stream and the Southern Ocean.

Two kinds of air pollution are overlapping more often

In New Mexico, where I live, we have some hot summer days when the reaction of vehicle emissions with sunlight creates so much ozone that the air becomes unhealthy, especially for people with asthma or other respiratory diseases. We also have some days when smoke particles in the air, from large wildfires that are often hundreds of miles away, pose a respiratory hazard.

And increasingly since 2000, according to research that I wrote about last week, we have some days when both types of pollution occur at unhealthy levels simultaneously — not just in New Mexico but throughout the West. That means millions of people in the region are exposed to a “double whammy,” as one researcher put it, of the harmful pollutants on more days each year.

The researchers blamed extreme heat and worsening wildfires for the increasing frequency of what they called “co-occurrences” of bad ozone and smoke pollution throughout the region. And they suggested that climate change is playing a role — which makes sense, since global warming has been linked both to more extreme heat events and to more large fires.

Quotable: “Something may not necessarily have a high likelihood of killing you personally in the short term,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist and one of the authors of the study. “But if you impose that same risk on tens of millions of people over and over again, the societal burden is actually very high.”

Don’t just watch: A film urges climate action

“A kick in the pants.” That’s what the director Adam McKay said he wanted his new movie, “Don’t Look Up,” to be.

A Netflix chart-topper, it stars Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence as scientists trying desperately to get leaders and the public to take seriously a planet-killing comet that’s hurtling toward Earth. The comet is a metaphor for climate change, and McKay, DiCaprio and Jonah Hill, who plays the White House chief of staff in the film, have been urging viewers to get involved in climate actions big and small.

As I wrote in my article this week, other Hollywood offerings have had real world effects: President Ronald Reagan resolved to prevent nuclear war after watching a 1983 TV movie. But there’s debate whether “Don’t Look Up” can do that — and whether McKay’s climate change metaphor worked at all.

Numbers: According to Netflix, which self-reports its figures, the movie is one of its most popular films ever, amassing 152 million hours viewed in a recent week.

Understand the Lastest News on Climate Change

A warming trend. European scientists announced that 2021 was Earth’s fifth hottest year on record, with the seven hottest years ever recorded being the past seven. A Times analysis of temperatures in the United States showed how 2021 outpaced previous years in breaking all-time heat records.

Finding a story by asking ‘really dumb questions’

This week in Times Insider, the section that explains who we are and what we do, Somini Sengupta, a climate reporter, talks about her inspiration for becoming a journalist, finding ideas and unwinding.

Also important this week:

-

Virginia Democrats are trying to block Andrew Wheeler, who served as E.P.A. chief under former President Trump, from taking up an environmental post in the state.

-

Politicians in Chile have called for a pause in lithium mining contracts.

And finally:

What climate change and Covid mean for skiing

More skiers in the United States are doing something you wouldn’t expect: skiing uphill. The reason has to do with both the coronavirus and climate change.

Ski touring, a hybrid style that combines elements of cross-country and downhill skiing, has long been popular in Europe. In North America, though, it’s generally only been practiced by athletes and mountaineers who want to trek up into the backcountry where they can ski on untouched powder.

That changed when the pandemic shut resorts across the country in 2020. Ski touring became the only affordable way for recreational skiers to get up the slopes.

Now lifts are open again, but touring seems to have taken hold as a safer, more reliable way to ski on a warming planet. Last year, over a million people in the United States used specialized touring gear. “It’s not linear growth,” said Drew Hardesty, a skier and forecaster at the Utah Avalanche Center. “It’s exponential.”

It’s safer because, experts say, climate change has made avalanche risks more unpredictable in the backcountry. It’s more reliable because warming has decreased snow cover. And on managed trails, resorts have the option to add artificial snow.

You can read the full article here.

If you’re not getting Climate Fwd: in your inbox, you can sign up here

We’d love your feedback on the newsletter. We read every message, and reply to many! Please email thoughts and suggestions to climateteam@nytimes.com.