A leader of armed confrontations at Wounded Knee and in Washington, he later shifted his focus to education, jobs and cultural renewal.

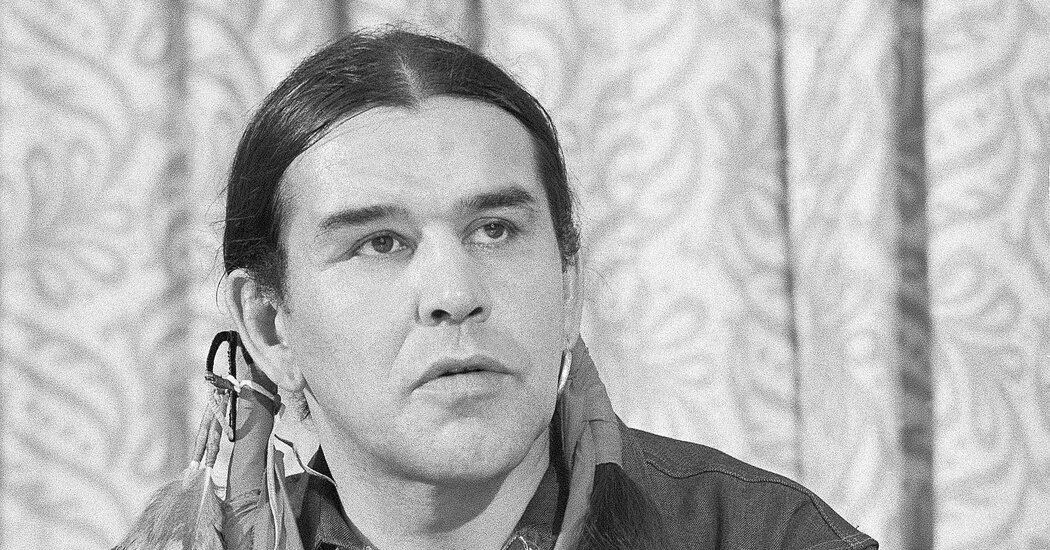

Clyde Bellecourt, a founder of the American Indian Movement who led violent protests in the 1970s at Wounded Knee, S.D., and in Washington over the federal government’s grim record of broken treaty obligations, and who later pressured sports teams to expunge their Native American nicknames, died on Tuesday at his home in Minneapolis. He was 85.

His wife, Peggy Sue (Holmes) Bellecourt, said the cause was complications of pancreatic cancer.

Mr. Bellecourt may not have been as well known to the general public as his fellow activists Dennis Banks and Russell Means, and his accomplishments may have been eclipsed by a checkered record of criminal arrests and internecine brawls, one of which ended with him shot in the stomach by a rival, Carter Camp, the movement’s newly elected national chairman, in 1973.

Regardless, he was a force to be reckoned with.

Mr. Bellecourt galvanized aggrieved but diffuse Native American dissidents after the publication of “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” (1970), Dee Brown’s scathing chronicle of the government’s historic betrayal of Indian treaties. He also dramatized their political, economic, social, cultural and educational agendas and redeemed his Ojibwe name, Nee-gon-we-way-we-dun, which means “Thunder Before the Storm.” (The Ojibwe are also known as the Chippewa tribe.)

Mr. Bellecourt defended the armed takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Washington in 1972 and the 71-day standoff at the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, during which two Native Americans were killed and a federal agent was paralyzed after being shot.

Wounded Knee was where, in 1890, in one of the last bloody conflicts of the American Indian Wars, about 350 Lakota men, women and children were massacred by U.S. troops.

“We are the landlords of the country, it is the end of the month, the rent is due, and A.I.M. is going to collect,” Mr. Bellecourt was quoted as saying.

By then he had already shifted from the politics of confrontation to educating his fellow Native Americans and the American public in general.

In 1972, he began the bilingual and bicultural Heart of the Earth Survival School. In later years he established the Peacemaker Center for Indian youth; the American Indian Movement Patrol, to provide security for the Minneapolis Indian community; a Legal Rights Center; the Native American Community Clinic; Women of Nations Eagle’s Nest Shelter; the International Indian Treaty Council; and the American Indian Opportunities Industrialization Center, a program to move welfare recipients to full-time jobs.

He also helped create the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and the Media, which urged professional, amateur and school teams to abandon nicknames like Redskins, Indians and Braves, which he saw as demeaning stereotypes.

“We’re trying to convince people we’re human beings and not mascots,” he said in 1992. “They’re making fools of themselves and of us in the process.”

In recent years both the Washington Redskins of the National Football League and Major League Baseball’s Cleveland Indians have dropped their old names.

On Facebook, the Grand Governing Council of the American Indian Movement lauded Mr. Bellecourt’s “fierce dedication, monumental presence and selfless leadership” and said that he “embodied the spirit of the American Indian Movement, the spirit of resistance, the strength and the resolve our people have held for over 530 years.”

On Tuesday, also on Facebook, Peggy Flanagan, Minnesota’s lieutenant governor, wrote that Mr. Bellecourt’s “legacy will live on in the policy changes that created curriculum and classrooms that are more supportive and welcoming of Native youth.”

Clyde Howard Bellecourt was born on May 8, 1936, on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northwestern Minnesota, the seventh of 12 children of Charles and Angeline Bellecourt. His father, an injured World War I veteran, was receiving a disability pension. Their home had no electricity or running water.

Clyde attended a Roman Catholic mission school run by Benedictine nuns on the reservation until he was a teenager. The family then moved to Minneapolis, where he struggled academically, dropped out of high school, failed to find a job and was jailed for burglaries and robberies.

In prison, he met Mr. Banks and Eddie Benton-Banai, who was running a cultural program for Native American inmates. After they were released, in mid-1968, they founded the American Indian Movement with George Mitchell, Charles Deegan and others to help urban Indians deal with discrimination, unemployment, poverty and insufficient housing. Mr. Bellecourt’s older brother Vernon was also active in the movement.

Mr. Bellecourt, who later worked for a utility company, was chosen as the movement’s first chairman and helped launch the so-called Trail of Broken Treaties, a long march from the West Coast to Washington in 1972.

In addition to his wife, whose Japanese American father was interred during World War II, Mr. Bellecourt is survived by four children, Susan, Tonya, Little Crow and Little Wolf; and a number of grandchildren.

He pleaded guilty following his arrest in 1985 in a drug possession case. He later said that the arrest and the two years he spent in prison had helped him break his addiction.

In 2016 he published an autobiography, “Thunder Before the Storm,” written with the journalist Jon Lurie. In it, Mr. Bellecourt wrote that before he could help heal others as a leader of A.I.M. in the late 1960s, he had to make peace with his creator and heal himself, along with Mr. Benton-Banai, in a prayerful sweat lodge ceremony — an experience that led to a transformation of the movement’s agenda, from violent confrontation to constructive engagement.

“I understood that the only way we were going to succeed in the Movement was to place healing and spirituality at the center of everything we did,” he wrote. “The spirits in the ceremony told us that we were to continue on our journey, that we had to bring back the spirit of the Indian people.”