This article is part of the Debatable newsletter. You can sign up here to receive it on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

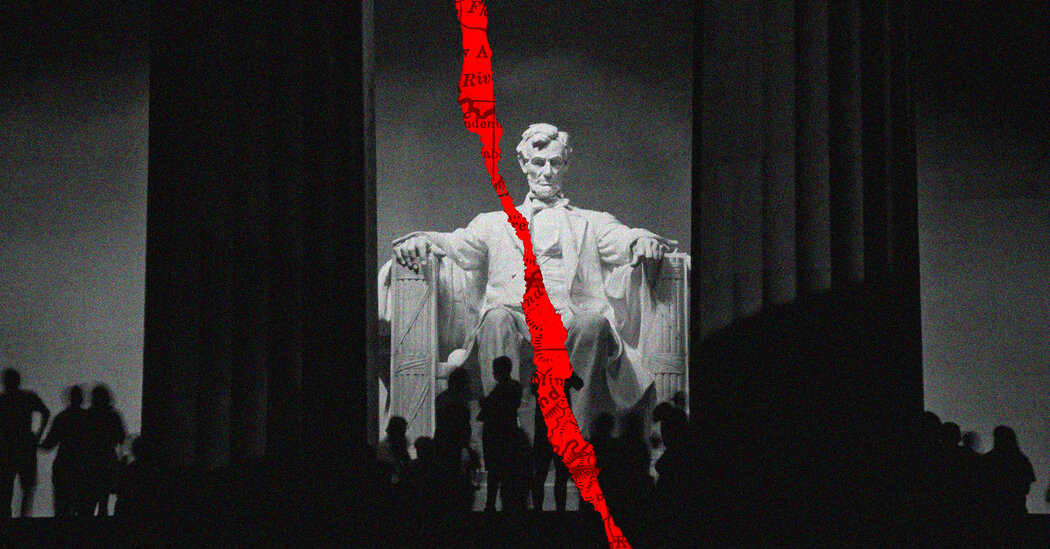

In January of last year, shortly after the storming of the Capitol, the pollster John Zogby conducted a national survey that yielded a troubling finding: A plurality of respondents — 46 percent — believed that the United States is headed for another civil war.

According to Barbara Walter, a political science professor at the University of California, San Diego, who studies civil wars, that belief is perfectly within the realm of reason.

“No one wants to believe that their beloved democracy is in decline, or headed toward war,” she writes in her new book, “How Civil Wars Start.” But “if you were an analyst in a foreign country looking at events in America — the same way you’d look at events in Ukraine or the Ivory Coast or Venezuela — you would go down a checklist, assessing each of the conditions that make civil war likely. And what you would find is that the United States, a democracy founded more than two centuries ago, has entered very dangerous territory.”

Should Americans take the prospect of another civil war seriously, or do such warnings constitute a misguided, perhaps even dangerous form of alarmism? Here’s what people are saying.

The case for concern

Walter served on an advisory committee to a C.I.A. task force that monitors countries and evaluates their risk of civil conflict. According to the data on which that task force relies, the United States during the Trump presidency regressed, for the first time since 1800, into what scholars call an “anocracy”: a system of government somewhere between democracy and autocracy. (The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Stockholm also recently listed the United States as a “backsliding” democracy.) Countries that bear this designation face a high risk of violence, including civil war.

So what would a 21st-century U.S. civil war look like? As David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, writes, it would “bear no resemblance to the consuming and symmetrical conflict that was played out on the battlefields of the 1860s.” Instead, the worst scenario would be “an era of scattered yet persistent acts of violence: bombings, political assassinations, destabilizing acts of asymmetric warfare carried out by extremist groups that have coalesced via social media.”

In the months before the Capitol attack, experts estimated that there were about 300 militia groups in the United States with a total of 15,000 to 20,000 active members, up to 25 percent of them veterans. These groups experienced a period of relative inactivity, according to a report by the Digital Forensic Research Lab at the Atlantic Council, but have resurfaced in recent months with a focus on local policies and government.

“Altogether, the threat of political violence in the United States may be diffuse, but it is growing,” the report reads. “Though extremist movements face more exposure and scrutiny, the threats they pose to the nation’s security and democratic foundations remain a paramount concern.”

In the view of Lilliana Mason, a Johns Hopkins University political scientist who studies polarization and political violence in America, the country could soon experience a conflagration “like the summer of 2020, but 10 times bigger.”

Even elected Republicans have been invoking the prospect of civil conflict. In December, before she was suspended from Twitter, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia conducted a Twitter survey to gauge interest in a “national divorce” between Republican- and Democratic-leaning states. In August, Representative Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina said, “If our election systems continue to be rigged and continue to be stolen, then it’s going to lead to one place and that’s bloodshed.”

Civil war, or ordinary crisis?

Certainly Walter’s argument has skeptics. The Times columnist Michelle Goldberg, for example, points out that the list of contemporary anocracies that have fallen into all-out civil war consists without exception of countries transitioning from authoritarianism to democracy. “It’s not clear, however, that the move from democracy toward authoritarianism would be destabilizing in the same way,” she writes. “To me, the threat of America calcifying into a Hungarian-style right-wing autocracy under a Republican president seems more imminent than mass civil violence.”

There is also good reason to doubt that a substantial share of Americans are willing to commit political violence. In a recent working paper, a team of researchers led by Sean J. Westwood of Dartmouth argued that polls showing otherwise are in fact “illusory, a product of ambiguous questions and disengaged respondents.” As it stands, political violence is quite rare in the United States, accounting for little more than 1 percent of violent hate crimes. “These findings suggest that although recent acts of political violence dominate the news, they do not portend a new era of violent conflict,” the authors wrote.

The Times columnist Ross Douthat agrees: “Despite fears that Jan. 6 was going to birth a ‘Hezbollah wing’ of the Republican Party, there has been no major far-right follow-up to the event, no dramatic surge in Proud Boys or Oath Keepers visibility, no campaign of anti-Biden terrorism. Republicans who believe in the stolen-election thesis seem mostly excited by the prospect of thumping Democrats in the midterms, and the truest believers are doing the extremely characteristic American thing of running for local office.”

Beyond public opinion, there are other limiting forces in American political life that make a civil war unlikely, William G. Gale and Darrell M. West of the Brookings Institution write.

-

Private, not public, militias: When Southern states seceded in 1860, they employed police forces, military organizations and state-sponsored militias. Today’s violent extremist groups, by contrast, wield no state-backed power.

-

No regional split: True, cities tend to lean Democratic and rural areas Republican. “But that is a far different geographic divide than when one region could wage war on another,” they write. “The lack of a distinctive or uniform geographic division limits the ability to confront other areas, organize supply chains, and mobilize the population.”

-

The federal justice system remains intact: “Although there has been a deterioration of procedural safeguards and democratic protections, the rule of law remains strong and government officials are in firm position to penalize those who engage in violent actions.”

As all these authors write, one can be skeptical of the civil war hypothesis and still be profoundly concerned about the state of U.S. democracy. “I know a lot of civil war scholars,” Josh Kertzer, a Harvard political scientist, tweeted recently, and “very few of them think the United States is on the precipice of a civil war.” But, he added, “The point isn’t that political scientists believe everything is fine!”

The danger of warning of war

In The Atlantic, Fintan O’Toole argues that prognostications of civil war, even when justified, can be dangerous, a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. For once belief in the inevitability of conflict takes root, so does the logic of the pre-emptive strike: “Do it to them before they do it to you. The other side, of course, is thinking the same thing.”

Drawing on his boyhood experience of the Troubles, he writes that 1972 “was one of the most murderous in Northern Ireland precisely because this doomsday mentality was shared by ordinary, rational people like my father. Premonitions of civil war served not as portents to be heeded, but as a warrant for carnage.”

Invocations of foreign-seeming forms of political disorder can also exoticize the present, concealing its continuities with the past, as the historian Samuel Moyn wrote in 2020. The notion that the United States risks losing its status as a full democracy only now because of Trump-era political violence sits uneasily with the history of slavery, the women’s suffrage movement, the racial terrorism of the post-Reconstruction era, the civil rights movement and the assassination of Martin Luther King, or even the domestic terrorism of the 1970s.

At best, Moyn wrote, bad comparisons that “abnormalize” the present are intellectually dishonest; at worst, they are politically useless, “delaying and distorting a collective resolve about what steps would lead us out of the present morass.”

At the time, Moyn was writing about warnings of fascism, but O’Toole applies a similar argument to warnings of civil war. “The comforting fiction that the U.S. used to be a glorious and settled democracy prevents any reckoning with the fact that its current crisis is not a terrible departure from the past but rather a product of the unresolved contradictions of its history,” he writes. “The dark fantasy of Armageddon distracts from the more prosaic and obvious necessity to uphold the law and establish political and legal accountability for those who encourage others to defy it. Scary stories about the future are redundant when the task of dealing with the present is so urgent.”

Do you have a point of view we missed? Email us at debatable@nytimes.com. Please note your name, age and location in your response, which may be included in the next newsletter.

READ MORE

“We’re Edging Closer to Civil War” [The New York Times]

“A new book imagines a looming civil war over the very meaning of America” [The Washington Post]

“We don’t need a civil war to be in serious trouble” [The Harvard Gazette]

“Mainstream presence of Proud Boys, other extreme groups creates mass radicalization fears” [PBS]

“Is the U.S. really heading for a second civil war?” [The Guardian]

WHAT YOU’RE SAYING

Here’s what a reader had to say about the last edition, “How to get through an Omicron winter”

Scott: “Perhaps because very young children haven’t seemed to get very sick from Covid, preschools were left out of whatever testing and protective protocols were developed for K-12, and the mentality has appeared to be, ‘Keep the day cares open at any cost so parents can keep going to work.’ Well, that cost is now coming due with the highest rates of pediatric hospitalizations yet. But still, the vulnerable age group of 0-4 is left out of the discussion.

“As the parent of a 3-year-old, I’m struggling. There’s no clear guidance, there’s little to no support, and there’s no clear, reliable word on when we can expect to see a vaccine available for our children — just constant dismissal that our kid will ‘likely’ not suffer serious illness or death. That’s not enough.”