Gov. Kathy Hochul unveiled a record-setting new budget plan, as state officials project balanced budgets through 2027, with none of the typical warnings of billion-dollar shortfalls.

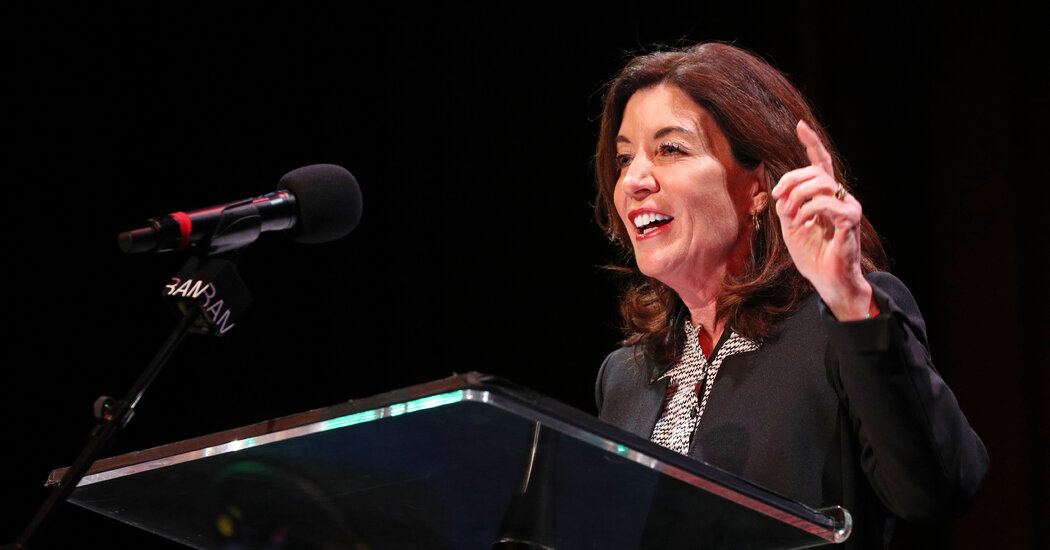

ALBANY, N.Y. — Gov. Kathy Hochul unveiled on Tuesday a record-setting $216.3 billion budget proposal meant to pay for increased spending on health care and education, and help spur New York’s economic recovery from the pandemic.

The budget reflects the state’s unusual change of fortune: Thanks to an influx of federal aid money, and last year’s tax increase, officials are projecting balanced budgets through 2027, rather than the typical warnings of billion-dollar shortfalls.

In a brief budget presentation, Ms. Hochul, a Democrat from Buffalo, characterized the spending plan as a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to make purpose-driven investments in our state and in our people that will pay dividends for decades.”

Her proposal includes several significant one-time infusions, including $2 billion in pandemic recovery initiatives, $2.2 billion in property tax relief for 2.5 million homeowners, $1 billion over three years in capital investments for transit-related projects and $350 million in pandemic relief for businesses, theaters and the musical arts.

Ms. Hochul’s fiscal plan, about $4.3 billion larger than the budget approved last year, delineated how the governor intends to pay for many of the policy priorities she outlined in her State of the State address earlier this month, including $1.6 billion for improvements to nursing homes and health care facilities and $1.2 billion in bonuses for the state’s exhausted health care work force.

She announced an investment of $1.4 billion to help subsidize child care for about 400,000 families, $150 million to expand tuition assistance programs, a $4 billion bond act to fund environment-related upgrades, and $32.8 billion in yet-to-be specified capital infrastructure investments.

In the coming months, Ms. Hochul will have to negotiate her proposed spending plan for the 2023 fiscal year, which begins on April 1, with the State Legislature. The governor has outsize influence in negotiations of the state budget, which often becomes a vessel to pass a raft of nonfiscal priorities that might be more politically difficult for lawmakers to pass individually.

For Ms. Hochul, successfully navigating the budget negotiations will be instrumental as she runs for a full term as governor, partly on her achievements since assuming office in August, when former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo resigned amid sexual harassment allegations. She has already raised nearly $21.6 million, her campaign said on Tuesday, a record-breaking haul for New York politics.

Ms. Hochul, unlike her predecessors, finds herself in the politically enviable position of helming a state in good financial health.

Mr. Cuomo warned just a year ago that, without significant federal aid, the state was staring at a daunting $15 billion deficit because of the pandemic, and would have to enact a “doomsday” budget with tax hikes and spending cuts. Before him, former Gov. David A. Paterson faced a ballooning state deficit and state debt during the Great Recession, which roiled the economy and decimated the state coffers.

Ms. Hochul inherited a state looking down the road at years of balanced budgets, thanks in part to revenue from income tax increases on the wealthy that the Democratic-controlled Legislature passed last year. That gives the governor more flexibility to steer money to fund her most immediate priorities, even though she will face the typical frenzy of lawmakers and special interest groups with ideas of their own of how to spend the state’s extra money.

But New York’s rosy fiscal outlook masks some uncertainty: The current projections rely on a significant influx of pandemic-era federal aid, about $22 billion over four years, an unsustainable revenue source that will evaporate over time. State officials used a large part of the federal aid in this year’s budget, which included $2.3 billion to help tenants late on rent and a $2.1 billion fund to provide one-time payments for undocumented workers.

And with so much of the state budget reliant on tax revenue from high-income earners, lingering questions about population loss, the future of remote work and how quickly Manhattan will rebound could have seismic effects.

New York lost more than 300,000 people in the past year, according to census records — the greatest loss of any state. New York City’s 9.4 percent unemployment rate is more than double the national average. Reversing that trend, in part by telegraphing that New York is open for business, will be crucial for the governor.

Ms. Hochul committed to placing 15 percent of the state’s operating expenses into reserves — a historic number, but less than the 17 percent figure recommended by independent budget analysts.

Nonetheless, fiscal experts said that with so much money to work with, the governor could help put New York on a path to financial stability, or increase spending on new programs to help people struggling during the pandemic and shore up floundering ones, focusing on child care, health care, housing, education, transportation and green infrastructure.

“We actually have enough money to do both — that’s the amazing thing,” said Andrew Rein, president of the nonpartisan Citizens Budget Commission. “The risk is the feeding frenzy, the fiscal cavorting, the fiscal hangover.”