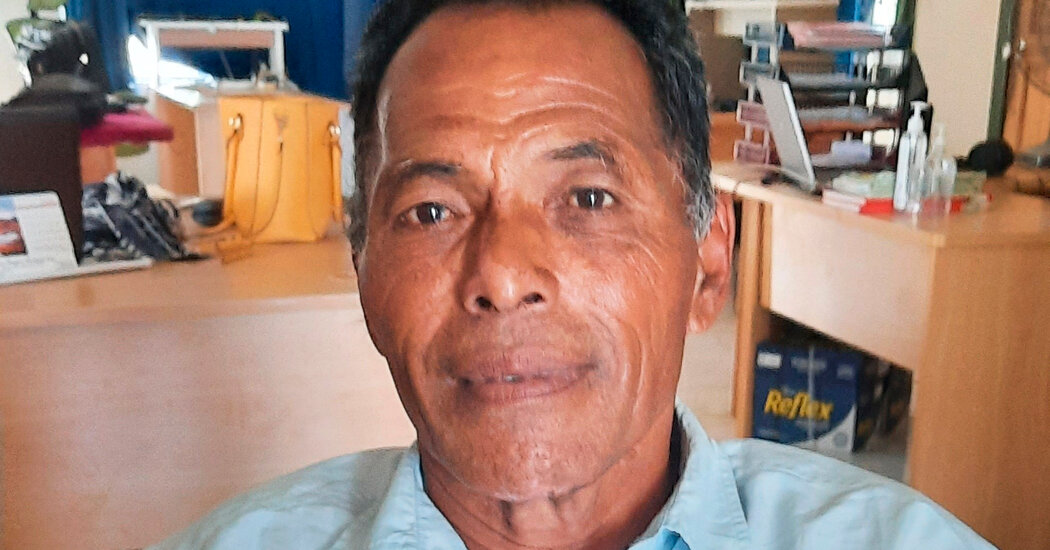

Lisala Folau, a retired carpenter, spent a night and day at sea after an undersea volcanic eruption sent waves crashing through his home on the island of Atata.

Lisala Folau had been at sea for about 12 hours, drifting between the islands of Tonga overnight after a tsunami hit his home, when he saw a police patrol boat.

Mr. Folau, 57, grabbed a rag and waved, hoping for rescue from the disaster caused by an undersea volcano’s eruption about 40 miles from Tonga. But the people on the police boat did not respond. Mr. Folau wasn’t even halfway through his trial of trying to reach safety.

The ordeal began when Mr. Folau, a retired carpenter, was painting at his home on the island of Atata, he told Broadcom FM, a Tongan radio station, according to a translated transcript of the interview shared by an editor at the radio station, George Lavaka, on Facebook. It was Saturday night, and the undersea volcano had just erupted, causing black rocks to rain from the sky and driving a wall of water onto the islands.

Nearly a week later, the full extent of devastation in Tonga is still not known because the disaster knocked out an undersea cable essential for efficient communication with the rest of the world. The blast also caused an enormous ash cloud that has contaminated drinking water sources and prevented relief flights from landing for four days. Despite the scope of disaster, as of Thursday night, the death toll was only at three.

Not long after the eruption Saturday night, Mr. Folau’s older brother managed to alert him that a tsunami wave was coming. With a nephew, he tried to help Mr. Folau, who said he was disabled and had trouble walking, as waves crashed through the house.

During a lull in the waves, they worked with several others to try to get to higher ground in Atata, where 106 people live, according to Tonga’s 2021 census. Around 7 p.m., Mr. Folau’s older brother yelled to the group that a big wave was coming.

“I just turned and looked at the wave, it was a bigger wave than the six meters that destroyed our house,” Mr. Folau said.

The wave, nearly 20 feet in his estimation, swept Mr. Folau and his niece, Elisiva, out to sea in the dark. Mr. Folau heard his son calling out, but he kept silent.

“My thinking was if I answered him he would come and we would both suffer so I just floated, bashed around by the big waves that kept coming,” Mr. Folau said.

Mr. Folau said he wanted to find land, but he also thought if he clung to a tree, his family would have an easier time finding his body.

About 12 hours had passed when he saw a police patrol boat heading to Atata, around 7 a.m.

“I grabbed a rag and waved but the boat did not see me,” Mr. Folau said. “It then was returning to Tonga and I waved again but perhaps they did not see me.”

Mr. Folau then set about trying to reach the island of Polo’a, arriving around 6 p.m. “I called and yelled for help but there was no one there,” he said.

Mr. Folau said his mind raced with thoughts of his family, including his niece, whom he had not seen since they were swept away, and other close relatives who had health problems.

He said these thoughts motivated him to get to Sopu, which is on the western edge of the capital, Nuku’alofa, on Tongatapu, the main island.

Mr. Folau arrived around 9 p.m., crawled to the end of a public road, then used a piece of timber as a walking stick. He walked until he found help from someone in a vehicle. He did not tell the radio station whether he knew the condition of his niece or other relatives, and communication with Tonga remained difficult on Friday.

“And it was the manna of God to me and my family, and the church as well as Atata, so unexpected that I survived after being washed away, floating and surviving the dangers I just faced,” he said.

Peter Lund, New Zealand’s acting high commissioner in Tonga, told The Associated Press that Mr. Folau’s story was in line with the timeline of the disaster and the report of a missing person on Atata. “It’s one of these miracles that happens,” Mr. Lund said.