In our series of letters from African writers, Algerian-Canadian football journalist Maher Mezahi, who is in Cameroon to cover the Africa Cup of Nations, reflects on how the recent deaths of fans at a stadium has left him with mixed feelings about the tournament.

When I was first asked to do a piece about my impressions about the tournament in Cameroon, I had wanted to compile a list of the things that make it so special and sets it apart from other major football competitions.

I was planning to celebrate African football.

After all, Afcon is a special tournament, adored by everyone on the continent and intrinsically linked to pan-African values.

The first two in 1957 and 1959, for example, were used in part as a statement against apartheid in South Africa.

Players, fans and journalists have all spoken about how it is closer to the true spirit of football, rather than the more sanitised and corporate tournaments elsewhere.

There is also the warm and friendly atmosphere as well as the pride that Afcon creates in all countries across the continent.

A carnival of super fans

Amongst the positive things are the medical protocols to deal with Covid-19, including pulmonary scans.

These are among the strictest in world football and intended to prevent any medical emergencies.

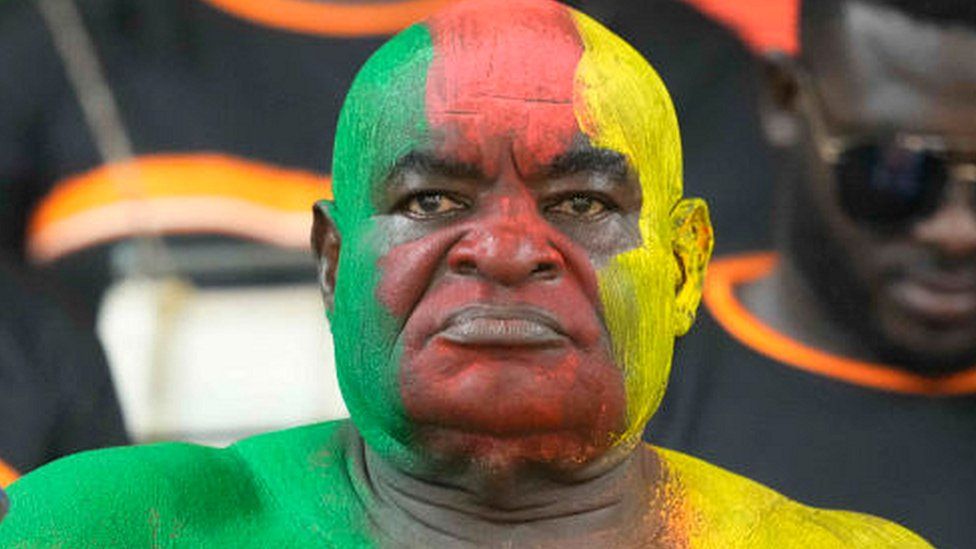

On the terraces, everyone lauds the carnival-like atmosphere that African football supporters manage to generate.

Recognisable super fans are present at every biennial championship.

Take Tunisia’s “Reda The Elephant”, who covers his belly in body paint has the best goal reactions, or Ivory Coast’s “Petit Bamba”, who orchestrates the National Elephants’ Supporters Committee dance moves.

“The atmosphere is so pure,” says Alex Cizmic, an Italian freelance journalist, who has often been amazed at the relaxed atmosphere around the teams.

“In 2019 in Egypt, I was fortunate enough to attend one of the Uganda Cranes’ training sessions. When it was over, I had a chat with star striker Farouk Miya, who I had never met before,” he recalls in a surprised tone.

“Then I arranged a quick call with his former coach Milutin Sredojevic, who I was in contact with. It all felt very familial.”

And smaller nations have shone.

The Gambia and Comoros were debutants in this edition of the tournament, and they have done their nations proud.

Before The Gambia played their first match against Mauritania, I asked a Gambian friend to write down what he felt as the anthem was playing.

“I felt a real sense of pride, love for country, and honour hearing the Gambian national team anthem for the first time,” he said.

“When the first goal went in, I couldn’t do anything. Deep inside of me I was just proud, knowing what the goal means. It really united our country.”

Abandoned shoes

But in one evening, all of the positive aspects of the Afcon have been overshadowed by a tragedy of unspeakable proportions.

As hosts Cameroon were set to play their second round match against Comoros at the new Olembe Stadium in the capital, Yaoundé, a bottleneck began to build outside.

I have been to football matches in seven African countries and every time I make the same observation: there are so many police officers and so little safety”

At around 19:30 local time, just half an hour before kick-off, thousands of fans were stuck in a crush that ended up killing eight people, including an eight-year-old boy, according to Cameroonian authorities.

I had arrived at the stadium earlier in the afternoon, but even several hours before the match started, the incessant cordoning off of spectators was irritating.

I have been to football matches in seven African countries and every time I make the same observation: there are so many police officers and so little safety.

For a stadium with a capacity of 60,000, it seemed extremely odd that journalists, supporters and everyone who was not a VIP were being ushered in through the same gate outside the campus.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Covid-19 testing and screening for vaccines further slowed down passage into the stadium.

I did not know what had transpired until late in the second half when a colleague nudged me in the ribs and whispered: “There’s trouble outside.”

We ran out, but there was nothing to see.

The only evidence of any problems was a handful of shoes and articles of clothing strewn on the ground.

A few minutes later rumours of deaths began filtering through.

In the press room, journalists began sharing documents that listed the victims as well as videos of the tragedy.

The following morning the Confederation of African Football (Caf) accepted shared responsibility for the incident and presented its condolences to the families.

But matches were not postponed and the tournament is continuing.

I do not think games should have taken place on Tuesday – the day after the tragedy.

It seemed disrespectful to the families, and everyone involved in the competition is still trying to process what happened.

It does not feel like a time to talk about or celebrate football.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica