At some point in the last 30 years, the concept of the “free world” fell out of favor.

Maybe it seemed dated once the Cold War ended. Or an afterthought in an era in which economic development, not political freedom, became the primary measure of human progress. Or too smug in an American culture increasingly obsessed with its own sins, current and original. Or no longer befitting countries where democratic norms and liberal principles were being eroded from within — from Hungary to India to the United States.

But we urgently need to restore the concept to its former place, both for its clarifying power and its moral force.

The prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine is being treated by Vladimir Putin’s many apologists as a case of reasserting Russia’s historic sphere of influence, or as predictable pushback against NATO’s eastward expansion — that is, as another episode in the game of great-power politics.

By this logic, the Kremlin’s aims are limited, its demands negotiable. It’s a tempting logic that implies diplomacy can work: Give Putin something he wants — say Ukraine won’t join NATO, or remove NATO forces from former Warsaw Pact states — and he’ll be satisfied.

But the logic ignores two factors: Putin’s personal political needs and his far-reaching ideological aims. Putin is neither a czar nor a real president, in the sense that he governs according to fixed rules that both legitimize and limit him. He’s a dictator, liable to charges of corrupt and criminal behavior, who has no guarantee of a safe exit from power and must contrive ways to extend his rule for life.

Whipping up periodic foreign crises to mobilize domestic support and capture global attention is a time-tested way in which dictators do this. So however the Ukrainian drama is resolved, there will be other Putin-generated crises. Appeasing him now emboldens him for later.

The second factor follows from the first. The ultimate way to consolidate dictatorship is to discredit democracy, to make it seem divided, tired and corrupt. There are many ways to do this and Putin practices plenty of them, from supporting extremist parties and politicians to sponsoring the Russian bots and trolls peddling conspiracy theories on social media.

The most effective method is a blunt power play that exposes the gap between the West’s high-flown rhetoric about democracy, human rights and international law, and its unheroic calculations about commercial advantage, military spending, energy dependence and strategic risks. Attacking Ukraine will have costs for Putin, but they’ll be more than compensated for if he can imbue the West with a profound sense of its own weakness. The bully’s success ultimately depends on his victim’s psychological surrender.

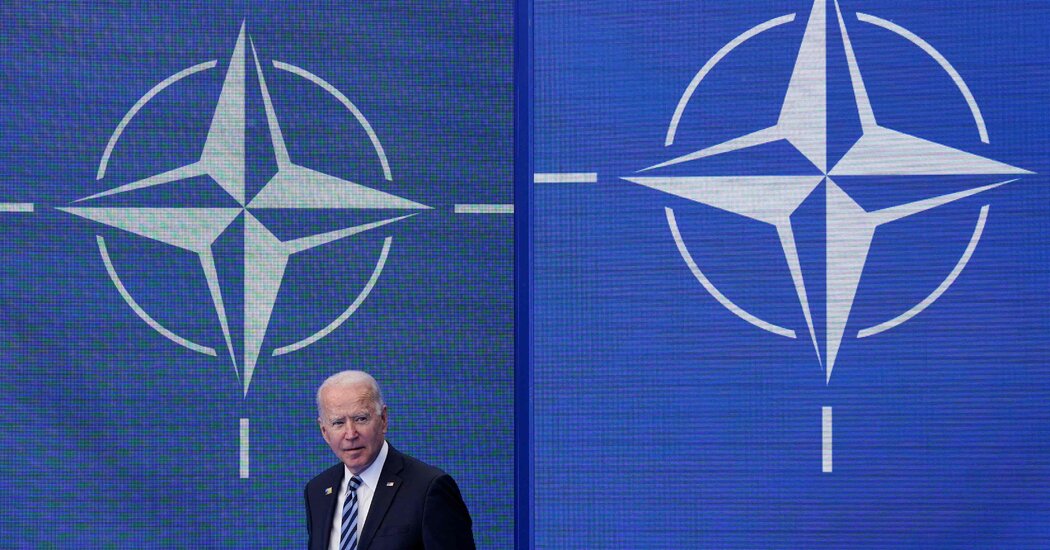

The best short-term response to Putin’s threats is the one the Biden administration is at last beginning to consider: The permanent deployment, in large numbers, of U.S. forces to frontline NATO states, from Estonia to Romania. Arms shipments to Kyiv, which so far are being measured in pounds, not tons, need to become a full-scale airlift. NATO troops need not, and should not, fight for Ukraine. But the least we owe Ukrainians is to give them a margin of deterrence that comes with being armed before they are invaded, along with a realistic chance to fight for themselves.

The longer-term response is to restore the concept of the free world.

What’s meant by that term? It isn’t just a list of states that happen to be liberal democracies, some bound together by treaty alliances like NATO or regional trading blocs like the European Union.

The free world is the larger idea that the world’s democracies are bound by shared and foundational commitments to human freedom and dignity; that those commitments transcend politics and national boundaries; and that no free people can be indifferent to the fate of any other free people, because the enemy of any one democracy is ultimately the enemy to all the others. That was the central lesson of the 1930s, when democracies thought they could win peace for themselves at the expense of the freedom of others, only to learn the hard way that no such bargain was ever possible.

The concept of the free world is not a perfect one — its constituent states are so often imperfect. It can be prone to overconfidence (as in Afghanistan) or strategic incoherence (as it was, for several years, in the Balkans) or bitter division (as it was over the war in Iraq).

But it would be foolish to think that the loss of Ukraine would mean nothing to the future of freedom elsewhere, including in the United States. Success in risky ventures tends to beget admiration, and Putin has never lacked for Western admirers, including a certain former — and possibly future — American president.

Putin seems to think that dividing and humiliating the West over Ukraine would reduce NATO and its partners to a collection of states, each fearful and pliable. It’s not a bad bet, and it won’t be easy to stop him. But a free world that understands that the alternative to hanging together is hanging separately can at least begin to face up to the menace he represents.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.