Why did the national emergency brought about by the Covid pandemic not only fail to unite the country, but instead provoke the exact opposite development, further polarization?

I posed this question to Nolan McCarty, a political scientist at Princeton. McCarty emailed me back:

With the benefit of hindsight, Covid seems to be the almost ideal polarizing crisis. It was conducive to creating strong identities and mapping onto existing ones. That these identities corresponded to compliance with public health measures literally increased “riskiness” of intergroup interaction. The financial crisis was also polarizing for similar reasons — it was too easy for different groups to blame each other for the problems.

McCarty went on:

Any depolarizing event would need to be one where the causes are transparently external in a way that makes it hard for social groups to blame each other. It is increasingly hard to see what sort of event has that feature these days.

Polarization has become a force that feeds on itself, gaining strength from the hostility it generates, finding sustenance on both the left and the right. A series of recent analyses reveals the destructive power of polarization across the American political system.

The United States continues to stand out among nations experiencing the detrimental effects of polarization, according to “What Happens When Democracies Become Perniciously Polarized?,” a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report written by Jennifer McCoy of Georgia State and Benjamin Press of the Carnegie Endowment:

The United States is quite alone among the ranks of perniciously polarized democracies in terms of its wealth and democratic experience. Of the episodes since 1950 where democracies polarized, all of those aside from the United States involved less wealthy, less longstanding democracies, many of which had democratized quite recently. None of the wealthy, consolidated democracies of East Asia, Oceania, or Western Europe, for example, have faced similar levels of polarization for such an extended period.

McCoy and Press studied 52 countries “where democracies reached pernicious levels of polarization.” Of those, “twenty-six — fully half of the cases — experienced a downgrading of their democratic rating.” Quite strikingly, the two continue, “the United States is the only advanced Western democracy to have faced such intense polarization for such an extended period. The United States is in uncharted and very dangerous territory.”

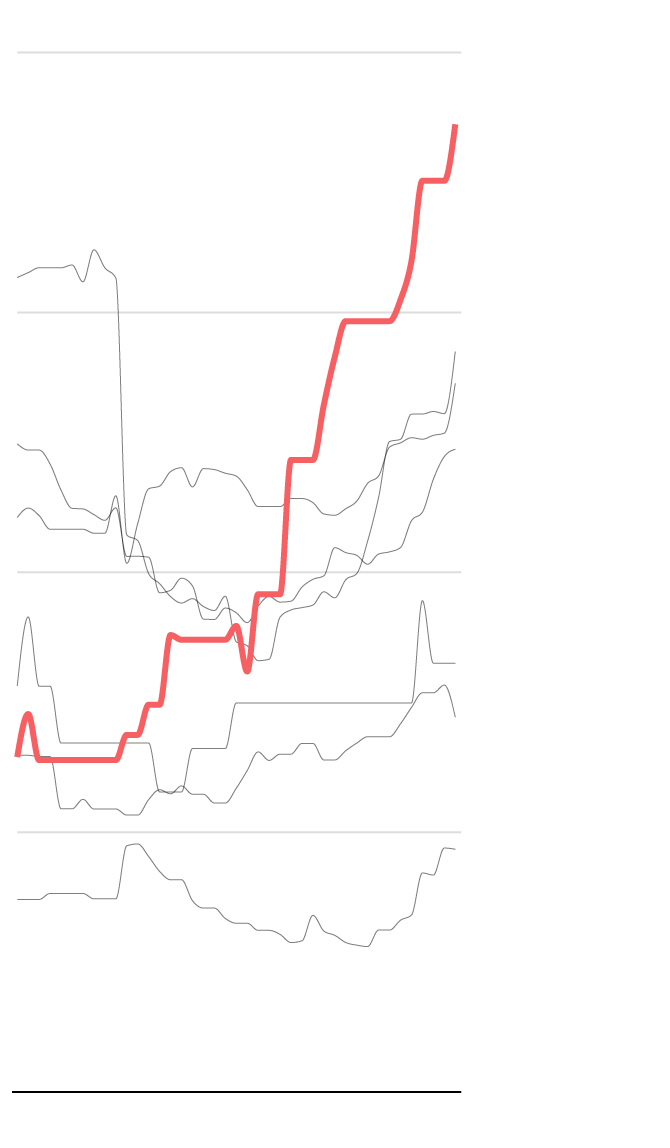

McCoy and Press analyzed the international pattern of polarization and again the United States stands out, with by far the highest current level of polarization compared with other countries and regions, as the accompanying graphic shows.

Levels of Polarization in the U.S. Stand Out

Political polarization rating

4

United States

3

Eastern Europe

Southern Europe

Latin America

and Caribbean

2

Australia and

New Zealand

Western Europe

1

Northern Europe

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

Political polarization rating

4

United States

3

Eastern Europe

Southern Europe

Latin America and Caribbean

2

Australia and New Zealand

Western Europe

1

Northern Europe

1980

1990

2000

2010

2020

In their report, McCoy and Press make the case that there are “a number of features that make the United States both especially susceptible to polarization and especially impervious to efforts to reduce it.”

The authors point to a number of causes, including “the durability of identity politics in a racially and ethnically diverse democracy.” As the authors note,

The United States is perhaps alone in experiencing a demographic shift that poses a threat to the white population that has historically been the dominant group in all arenas of power, allowing political leaders to exploit insecurities surrounding this loss of status.

An additional cause, the authors write, is that

binary choice is deeply embedded in the U.S. electoral system, creating a rigid two-party system that facilitates binary divisions of society. For example, only five of twenty-six wealthy consolidated democracies elect representatives to their national legislatures in single-member districts.

Along the same lines, McCoy and Press write that the United States has “a unique combination of a majoritarian electoral system with strong minoritarian institutions.”

“The Senate is highly disproportionate in its representation,” they add, “with two senators per state regardless of population, from Wyoming’s 580,000 to California’s 39,500,000 persons,” which, in turn, “translates to disproportionality in the Electoral College — whose indirect election of the president is again exceptional among presidential democracies.”

And finally, there is the three-decade-old trend of partisan sorting, in which

the two parties reinforce urban-rural, religious-secular, and racial-ethnic cleavages rather than promote crosscutting cleavages. With partisanship now increasingly tied to other kinds of social identity, affective polarization is on the rise, with voters perceiving the opposing party in negative terms and as a growing threat to the nation.

Two related studies — “Inequality, Identity and Partisanship: How redistribution can stem the tide of mass polarization,” by Alexander J. Stewart, Joshua B. Plotkin and McCarty, and “Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline,” by Stewart, McCarty and Joanna Bryson — argue that aggressive redistribution policies designed to lessen inequality must be initiated before polarization becomes further entrenched. The fear is that polarization now runs so deep in the United States that we can’t do the things that would help us be less polarized.

“The success of redistribution at stemming the tide of polarization in our model is striking,” Stewart, Plotkin and McCarty write, “and it suggests a possible path for preventing such attitudes from taking hold in future.”

In a reflection of the staying power of polarization, the authors observe that “once polarization sets in, it typically remains stable under individual-level evolutionary dynamics, even when the economic environment improves or inequality is reversed.”

In response to my emailed inquiries, Stewart explained:

A key finding in our studies is that it really matters when redistributive policies are put in place. Redistribution functions far better as a prevention than a cure for polarization in part for the reason your question suggests: If polarization is already high, redistribution itself becomes the target of polarized attitudes.

In other words, a deeply polarized electorate is highly unlikely to support redistribution that would benefit their adversaries as well as themselves.

In addition, Stewart wrote, polarization can arise independently from conditions of increasing inequality:

We find that cultural, racial and values polarization can emerge even in the absence of inequality, but inequality makes such polarization more likely, and harder to reverse. We also find that the features of identity which are most salient shift over time, with the process of “sorting” of identity groups along political lines driven by similar forces to those that drive high polarization. And so cultural, racial and values polarization are a force independent of inequality, with inequality acting as a complementary force that points in the same direction, and redistribution a force that acts in opposition to both.

In “Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline,” Stewart, McCarty and Bryson argue that economic scarcity acts as a strong disincentive to cooperative relations between disparate racial and ethnic groups, in large part because such cooperation may produce more benefits but at higher risk:

Interactions with more diverse out-group members pool greater knowledge, applicable to a wider variety of situations. These interactions, when successful, generate better solutions and greater benefits. However, we also assume that the risk of failure is higher for out-group interactions, because of a weaker capacity to coordinate among individuals, compared to more familiar in-group interactions.

In times of prosperity, people are more willing to risk failure, they write, but that willingness disappears when populations are

faced with economic decline. We show that such group polarization can be contagious, and a subpopulation facing economic hardship in an otherwise strong economy can tip the whole population into a state of polarization. Moreover, we show that a population that becomes polarized can remain trapped in that suboptimal state, even after a reversal of the conditions that generated the risk aversion and polarization in the first place.

At the same time, the spread of polarization goes far beyond politics, permeating the culture and economic structure of the broader society.

Alexander Ruch, Ari Decter-Frain and Raghav Batra studied the political and ideological profiles of purchasers of consumer goods in their paper “Millions of Co-purchases and Reviews Reveal the Spread of Polarization and Lifestyle Politics across Online Markets.” Using “data from Amazon, 82.5 million reviews of 9.5 million products and category metadata from 1996-2014,” the authors determined which “product categories are most politically relevant, aligned, and polarized.”

They write:

For example, after Levi Strauss & Co. pledged over $1 million to support ending gun violence and strengthening gun control laws, the jean company became progressively aligned with liberals while conservatives aligned themselves more with Wrangler. The traces of lifestyle politics are pervasive. For example, analyses of Twitter co-following show the stereotypes of “Tesla liberals” and “bird hunting conservatives” have empirical support.

Analyzing these “pervasive lifestyle politics,” Ruch, Decter-Frain and Batra find that “cultural products are four times more polarized than any other segment.”

They also found lesser but still significant polarization in consumer interests in other categories:

The extent of political polarization in other segments is relatively less; however, even small categories like automotive parts have notable political alignment indicative of lifestyle politics. These results indicate that lifestyle politics spread deep and wide across markets.

Further evidence of the entrenchment of political divisiveness in the United States emerges in the study of such related subjects as “social dominance orientation,” authoritarianism, and ideological and cognitive rigidity.

In a series of papers, Mark Brandt, Jarrett Crawford and other political psychologists dispute the argument that only “conservatism is associated with prejudice” and that “the types of dispositional characteristics associated with conservatism (e.g. low cognitive ability, low openness) explain this relationship.”

Instead, Crawford and Brandt argue in “Ideological (A)symmetries in prejudice and intergroup bias,” “when researchers use a more heterogeneous array of targets, people across the political spectrum express prejudice against groups with dissimilar values and beliefs.”

Earlier research has correctly found greater levels of prejudice among conservatives, they write, but these studies have focused on prejudice toward “liberal-associated” groups: minorities, the poor, gay people and other marginalized constituencies. Crawford and Brandt contend that when the targets of prejudice are expanded to include “conservative-associated groups such as Christian fundamentalists, military personnel and ‘rich people,’” similar levels of prejudice emerge.

“Low Openness to experience is associated with prejudice against groups seen as socially unconventional (e.g. atheists, gay men and lesbians), whereas high Openness is either associated with prejudice against groups seen as socially conventional (e.g. military personnel, Evangelical Christians),” they write. “Whereas high disgust sensitivity is associated with prejudice against groups that threaten traditional sexual morality, low disgust sensitivity is associated with prejudice against groups that uphold traditional sexual morality.”

Finally, “people high in cognitive ability are prejudiced against more conservative and conventional groups,” while “people low in cognitive ability are prejudiced against more liberal and unconventional groups.”

In “The role of cognitive rigidity in political ideologies,” Leor Zmigrod writes that the “rigidity-of-the-right hypotheses” should be expanded in recognition of the fact that “cognitive rigidity is linked to ideological extremism, partisanship, and dogmatism across political and nonpolitical ideologies.”

Broadly speaking, Zmigrod wrote in an email, “extreme right-wing partisans are characterized by specific psychological traits including cognitive rigidity and impulsivity. This is also true of extreme left-wing partisans.”

In a separate paper, “Individual-Level Cognitive and Personality Predictors of Ideological Worldviews: The Psychological Profiles of Political, Nationalistic, Dogmatic, Religious and Extreme Believers,” Zmigrod wrote:

When a series of cognitive behavioral measures were used to assess mental flexibility, and political conservatism was disentangled from political extremity, dogmatism, or partisanship, a clear inverted-U shaped curve emerged such that those on the extreme right and extreme left exhibited cognitive rigidity on neuropsychological tasks, in comparison to moderates.

While the processes Zmigrod describes characterize the extremes, the electorate as a whole is moving farther and farther apart into two mutually loathing camps.

In “The Ideological Nationalization of Partisan Subconstituencies in the American States,” Devin Caughey, James Dunham and Christopher Warshaw challenge “the reigning consensus that polarization in Congress has proceeded much more rapidly and extensively than polarization in the mass public.”

Instead, Caughey and his co-authors show

a surprisingly close correspondence between mass and elite trends. Specifically, we find that: (1) ideological divergence between Democrats and Republicans has widened dramatically within each domain, just as it has in Congress; (2) ideological variation across senators’ partisan subconstituencies is now explained almost completely by party rather than state, closely tracking trends in the Senate; and (3) economic, racial, and social liberalism have become highly correlated across partisan subconstituencies, just as they have across members of Congress.

Caughey, Dunham and Warshaw describe the growing partisan salience of racial and social issues since the 1950s:

The explanatory power of party on racial issues increased hugely over this period and that of state correspondingly declined. We refer to this process as the “ideological nationalization” of partisan subconstituencies.

In the late 1950s, they continue,

party explained almost no variance in racial conservatism in either arena. Over the next half century, the Senate and public time series rise in tandem.” Contrary to the claim that racial realignment had run its course by 1980, they add, “our data indicate that differences between the parties continued to widen through the end of the 20th century, in the Senate as well as in the mass public. By the 2000s, party explained about 80 percent of the variance in senators’ racial conservatism and nearly 100 percent of the variance in the mass public.

The three authors argue that there are a number of consequences of “the ideological nationalization of the United States party system.” For one, “it has limited the two parties’ abilities to tailor their positions to local conditions. Moreover, it has led to greater geographic concentration of the parties’ respective support coalitions.”

The result, they note,

is the growing percentage of states with two senators from the same party, which increased from 50 percent in 1980 to over 70 percent in 2018. Today, across all offices, conservative states are largely dominated by Republicans, whereas the opposite is true of liberal states. The ideological nationalization of the party system thus seems to have undermined party competition at the state level.

As a result of these trends, Warshaw wrote me in an email,

It’s going to be very difficult to reverse the growing partisan polarization between Democrats and Republicans in the mass public. I think this will continue to give ideological extremists an advantage in both parties’ primaries. It also means that the pool of people that run for office is increasingly extreme.

In the long term, Warshaw continued,

there are a host of worrying possible consequences of growing partisan polarization among both elites and the public. It will probably reduce partisans’ willingness to vote for the out-party. This could dampen voters’ willingness to hold candidates accountable for poor performance and to vote across party lines to select higher-quality candidates. This will probably further increase the importance of primaries as a mechanism for candidate selection.

Looking over the contemporary political landscape, there appear to be no major or effective movements to counter polarization. As the McCoy-Press report shows, only 16 of the 52 countries that reached levels of pernicious polarization succeeded in achieving depolarization and in “a significant number of instances later repolarized to pernicious levels. The progress toward depolarization in seven of 16 episodes was later undone.”

That does not suggest a favorable prognosis for the United States.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.