I was looking up at the head, but I was mistaken. Charles Ray was instructing me to look at the foot.

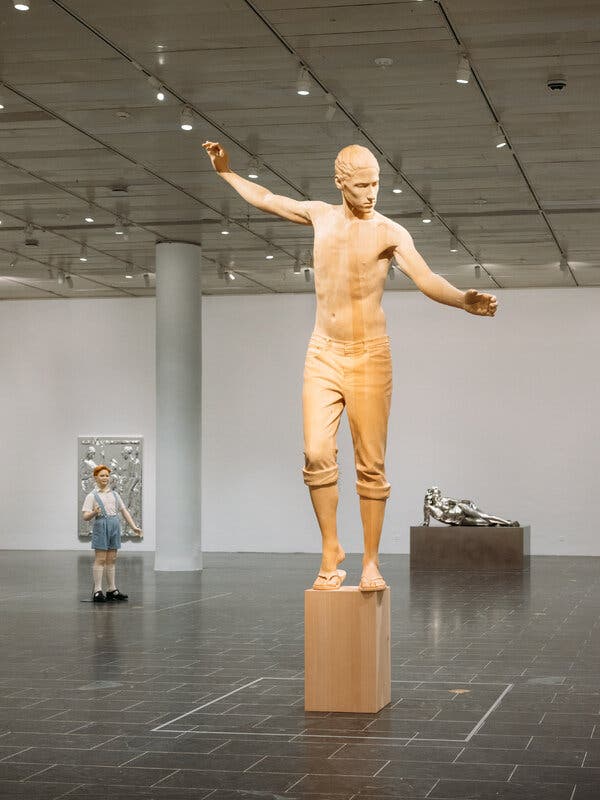

It was a freezing morning, and Ray and his crew had just finished installing a new work by this Los Angeles sculptor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was, like every Ray installation, a logistical feat — his strangely sized nudes or eerie wrecked cars can weigh four tons or more — but Omicron breakouts had wrought havoc on the movement of sculptures and technicians, and this one almost didn’t make it to New York. “Archangel,” 13.5 feet tall and seven years in the making, depicts a seminude young man in flip-flops and rolled-up jeans, carved from cypress by woodworkers in Japan. The pandemic prevented Ray from traveling to Osaka to approve the final work, and shipping troubles almost kept it from reaching New York — “Archangel” had to be flown to LAX and driven cross-country.

At last it was here. The surfer dude of “Archangel” is no messenger of God, and yet his body appears almost to be undergoing an apotheosis. His facial features are soft; his hair is done up in a topknot. The waistband of his trousers curves out slightly from the torso. Lower down the sculpture, though, are breathtaking vestiges of humanity. On his Achilles tendons, for instance, which the Japanese craftsmen scored a dozen times each. There are gentle gashes on the arches of his feet, and his half-visible foot soles. A single timber runs from his head through his big toe to the floor, and reveals that the figure and the block he stands on are one and the same.

Ray’s perfectionism has sometimes tended to the fetishistic, but never so literally as here. “The ladies at the Met just go crazy over his feet,” Ray says with an impish smile.

“Archangel” is the most towering presence in “Charles Ray: Figure Ground,” opening this weekend, which introduces a new generation to America’s profoundest and most challenging sculptor — as well as its slowest. Ray emerged in the mid-1970s as a keen ironist questioning sculpture’s fundamental principles by incorporating performance and process into his abstract assemblages. But in the 1990s, he shocked the Los Angeles art world by reintroducing the human figure: first through commercial mannequins, and later in exacting sculptures of nude and clothed Americans, carved both by hand and with advanced machines, whose sumptuous surfaces of steel and wood stood out in an unmonumental age.

When he turned to cypress in the 2000s, Ray tells me, “everyone was using old socks and teddy bears and stuff. All contemporary art smelled like a secondhand thrift store. And I had this beautiful piece that just reeked of Japan.”

One Ray exhibition is rare enough, given the speed at which the 69-year-old artist works. (His last significant museum presentation in New York took place in 1998.) Yet this season he’ll have no fewer than four shows on view. Last month at Glenstone, the serene private museum outside Washington, the collectors Mitchell and Emily Wei Rales premiered the third rotation of a yearslong rotating display of Ray’s work, juxtaposing one of his earliest post-minimal sculptures of steel beams and concrete blocks with a life-size self-portrait cast in a surprising new medium: airy, handmade white paper.

In February, Ray opens two more shows in Paris — at the Centre Georges Pompidou and at the Bourse de Commerce, which houses the private collection of François Pinault — that both include significant new works. This quartet of exhibitions, plus a major commission for this spring’s Whitney Biennial, may have been an administrative nightmare. (“Covid compressed them all together,” the artist regrets.) But it’s a summation moment for an artist who has thought harder than anyone about how to haul sculpture into the 21st century, and to retain the distinction of three-dimensional art in a world reshaped by flat screens.

His sculpture can be rascally. It can be anatomically explicit, though no more than Greek marbles or vases. Certainly it can be bizarre. (At the Pompidou, a new work in painted paper, depicting a reclining woman pleasuring herself, bears the eye-popping title “Portrait of the Artist’s Mother.”)

Learn More About the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- $125 Million Donation: The largest capital gift in the Met’s history will help reinvigorate a long-delayed rebuild of the Modern wing.

- Recent Exhibits: Our critics review a masterpiece “African Origin” show, an Afrofuturist period room and a round-the-world tour of Surrealism.

- Behind the Scenes: A documentary goes inside the Met to chronicle one of the most challenging years of its history.

- A Guide to the Met: From the must-see galleries to the lesser-known treasures, here’s how to make the most of your visit.

Like Jeff Koons, Ray since 1990 has made sculptures rooted in everyday American culture, with extremely finished surfaces, that cost millions. Unlike Koons, Ray has channeled his Americana through a profound engagement with the whole history of Western sculpture, from archaic Greek statuary to the bronzes of Rodin and the welded steel of David Smith and Anthony Caro. Classical and modern, universal and particular, grand and everyday, his reclining nudes or wrecked cars appear to slide through time itself.

“The pace and rate at which Ray works are important,” says Hamza Walker, the director of the nonprofit art space LAXART in Los Angeles. “It’s perverse on the one hand; he could sit with something for 20 years.” Ray, he observes, “distills down what we think we know, and it somehow becomes resonant, and produces reflections that show there’s so much more here than you know.”

“Archangel” had a classically long gestation. He conceived of it in January 2015 — when, days after the Pompidou invited the artist to present an exhibition, terrorists murdered the editors of Charlie Hebdo and the patrons of a kosher supermarket. Ray went to the city in mourning, stood outside the museum, and had a vision of an angel descending to Paris, a perfect being alighting on shaky ground.

“I wasn’t trying to make a homage or anything, but I was really shocked,” Ray remembers. “I don’t know why, but Gabriel just struck me. He’s honored in Jewish culture, Christian culture and Muslim culture.”

Back in L.A. he had a model stand on a two-foot plywood pedestal, and while he was photographing him he tried to keep him on his toes. “I had a big stick, and I was banging on the box, really whaling on it. So he wasn’t just plopped on his feet. Because I wanted him to be alighting down to the ground.”

From the photographs he made patterns of clay, then of a plaster-like substance called Forton, and later of fiberglass. Only years into the process did he turn to wood, engaging the master carver Yuboku Mukoyoshi to translate the fiberglass pattern into hinoki cypress. The carver and his assistants found the suitable wood planks, seasoned them, glued them together, and chiseled the figure to perfection without the help of sandpaper.

When the work was finished, Ray says, “it was interesting to me that what was most present were the feet. And as you moved up it, it got more and more remote, from his hands all the way to that ridiculous man-bun. That was, to me, like a moon of Pluto or something.” The sculpture had become, after all these years, about the protraction of the human foot and the celestial head. “He’s very elongated, very tall, very sexual,” Ray tells me. “All my gay friends really, really like it a lot.”

Each of Ray’s four new shows is spare, nonlinear, and choreographed down to the square inch.The Met show occupies the whole Cantor Exhibition Hall, but features only 19 works in two giant rooms. The Pompidou has just 20. At Glenstone the Ray gallery contains only four works, plus a fifth outdoors: his “Horse and Rider,” (2014), depicting the artist in baggy jeans and deck shoes, slouching on an old Hollywood nag. Another “Horse and Rider” now stands outside the Bourse de Commerce: 9.5 tons of solid, computer-milled stainless steel, an over-the-hill horseman to rival the nearby equestrian statues of Henri IV and Louis XIV.

Working outdoors can be tricky for him, and two of his nude sculptures — both in the Met show — have been removed from public view in the past: “early statues to be toppled in this age of cultural reckoning,” as Ray writes in the catalog. “Boy With Frog” (2009), an 8-foot youth of white-painted steel, previously stood in Venice but was removed after a furious Facebook campaign against the public presence of a nude child. The two-figure “Huck and Jim” (2014), depicting Twain’s characters in the altogether and not quite touching, was meant to stand outside the Whitney Museum of American Art’s new home; the museum declined to show it outdoors, fearful of offending passers-by.

When many artists and institutions have shied from the slightest ambiguity around race, sex or childhood, Ray has pushed further, in the Met’s other astounding new work, “Sarah Williams.” Here Huck and Jim return, clothed this time. In a scene drawn from the novel, the boy has donned a woman’s dress before going into town (where he will say his name is Sarah Williams). Huck’s eyes are clamped shut. The fugitive slave kneels behind him, perhaps pausing from adjusting the costume. What unites both pairs is gleaming stainless steel: metal that grounds them in space, and mirrors our own regard.

Ray is now a paragon of the L.A. art world, renowned for his hourslong daily walks in the Santa Monica Mountains and west of the 405. But he is a child of the Midwest, born in Chicago in 1953. As teenagers, he and his brother were enrolled in a grim Illinois boarding school, run half by the military, half by Benedictine monks, its discipline softened only by weekend studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The military school did not leave him a believer, but he remains a devoted student of ancient philosophy and Christian theology. A favorite word of his is pneuma: “the breath of life,” in Greek, which he first learned in one of his religion classes.

While an undergraduate at the University of Iowa, Ray began making performative sculptures such as “Plank Piece” (1973), for which the artist pinned his body in midair between a wooden board and the wall, his limbs slack, his long hippie’s hair obscuring his face. To some it appeared like a parody of Richard Serra, who propped steel plates against one another. But Ray was already thinking about how the human body could be a sculptural element with its own abstract force.

“People would say, ‘Oh, that must have hurt! Looks like a car wreck! Looks like a Goya!’ And I would totally deny the empathetic aspect. I would say, ‘No. It’s about a relationship between a wall, a plank and a body. That’s it.’ Ridiculous. But that was the moment.”

Ray moved west in 1981 to teach at the University of California, Los Angeles. Chris Burden was already there, but Ray’s arrival initiated a turnover in the faculty that affirmed Los Angeles (unlike New York) as a city where schools formed the core of the artistic scene. It’s hard to overstate the artistic firepower that would soon assemble in U.C.L.A.’s faculty lounge: Mike Kelley, Nancy Rubins, Paul McCarthy, Lari Pittman, Barbara Kruger, James Welling, John Baldessari and Catherine Opie all became Ray’s colleagues.

“He really pushed this idea that the medium of sculpture was space, as opposed to clay or wood,” recalls the sculptor Frank Benson, who studied with Ray and later worked in his studio.

In 1990, Ray acquired a department-store mannequin and affixed it with a new head, whose soft features and oversized glasses made him look just like the artist. This “Self-Portrait” reoriented Ray’s career — beginning a decades-long quest to reinscribe the figure into sculpture without rejecting the inheritance of modern art. Next came “Male Mannequin,” a stripped-off dummy whose genitals Ray modeled on his own. There was “Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley…” (1992), an onanistic orgy of eight Ray mannequins on view at the Bourse de Commerce, and later “Family Romance” (1993), now at the Met: a family of four, holding hands, all nude, the parents too short and the children too tall, to create the creepiest of nuclear households.

Especially in the context of Kelley, McCarthy and his other U.C.L.A. faculty-mates, the mannequins were read as uncanny totems of consumer society, abject, even depraved. Which left Ray dismayed. “My struggle — struggle might be the wrong word; my development — was trying to move through subject matter into sculpture,” he says now. “With ‘Oh! Charley, Charley, Charley…,” I was thinking death, like ‘Burghers of Calais.’”

He wanted to make sculpture that was figurative without being pictorial, that drew on tradition but didn’t come into the gallery on “a Freudian surfboard,” to use Ray’s high-L.A. term. That meant giving up the mannequins, and entering into a deep, slow engagement with the relationship between a work’s individual parts and sculptural whole. “Tractor” (2005) at the Met, is a prime example: an aluminum copy of a past-its-use-date farm machine, every tread and tube and gasket sculpted by hand.

“Some people saw it and thought, ‘Oh, you painted a tractor silver,’” says Benson, one of Ray’s studio assistants for “Tractor.” “But I feel Charley was very excited that the interior of the tractor had also been sculpted. No one would ever see that work that was inside the transmission. But he and anyone who knew about the work would know it was complete.”

His fastidiousness has never calcified into a streamlined process. Ray’s studios — one in Santa Monica, two in the San Fernando Valley — are very far away from Damien Hirst’s factory floor. They’re more like laboratories, where a given motif can pass through countless editions of clay, foam, plaster and fiberglass; get photographed or scanned, then edited with computer software; and then be sculpted again.

How do you make a solid object that matters — that endures — in a world of liquid images? Ray’s answer, and the key word for his legion of curatorial and academic fans, is what he calls “embedment”: a kind of ontological rightness, an implantation within a certain space and time and society. That embedment can take place through the weight of the stainless steel or the careful soldering of the aluminum, or the classicized majesty he brings to his subjects. A homeless woman asleep on a bench. A squinting woman reclining in the nude. A man with a beatific Buddha grin eating a hamburger.

Each has been carved with the seriousness sculptors once reserved for gods, but in forms that reflect how modernity took gods down from their pedestals. “I kind of spent my life trying to figure out a way to embed sculptures in the world — how to make it so it doesn’t look like, Oh, who put that here? How long is that thing going to be here? But to be kind of made of the world around them.” When he achieves that, the sculptures can take on the near-abstraction of Rodin’s Balzac, in the gallery right outside the Met show. We leave the realm of biography and information, and we experience breath, pneuma, life itself.

“When you get to the more volatile social subject matter, I often think it starts as a provocation or a bad-boy experiment, which is a prod for him to start thinking,” says Jack Bankowsky, a former editor of Artforum who organized a renowned 2014 exhibition of Ray, Koons, and Katharina Fritsch. “That kicking-the-hornet’s-nest aspect is definitely part of his personality, but he sculpts into it, and the complexity that we associate with his work is what comes out the other end.”

In “Huck and Jim,” the flesh of both characters is transmuted into stainless steel. Jim stands upright. Huck is bent at the waist, hand cupped as if reaching into a river. Ostensibly it was their nudity that spooked the Whitney, but the true precarity of the sculpture is Jim’s right hand, hovering gently over Huck’s lower back. In the space between lies a whole tangle of desires and sorrows.

“‘Huck and Jim’ is quite profound as a monument,” says Walker, who is currently organizing an exhibition of decommissioned Confederate monuments for LAXART. “This is like ur-Americana. These are not clothed soldiers, or men embodying virtue, but they somehow embody a national narrative, a national identity. We have this notion about how a monument should function. And then Charles Ray actually gives us something on which to reflect, and it’s like, No, no, no! Put the clothes back on!”

“There’s a disjuncture in it, which I got from Smith and Caro,” Ray says of the not-touching nudes. A similar charged separation recurs in “Sarah Williams,” where the positions are reversed: the cross-dressing Huck stands upright, while Jim crouches behind him, an arrangement of Black and white models that feels even more politically fraught.

But look closely at Jim’s right hand. Notice the fish hook sculpted in relief in his half-clenched palm — the hook which, in Twain’s novel, Jim uses to fashion Huck’s dress. Theirs is an emotional, historical, and racial entwinement in which the parts and the whole cannot be sundered. They are embedded in each other, as “Sarah Williams” is embedded in our space.

Last year, on a solo drive north from Los Angeles, Ray suffered a serious car accident. He broke his clavicle, his elbow, almost every rib in his body. And yet everyone I spoke to, from the curators to his studio assistants to his wife, the book designer Silvia Gaspardo-Moro, told me Ray has come to these new exhibitions with a renewed vigor. He is working a little faster than before, and pushing into realms unknown. “I was really surprised that he dared to go so classical” in these new shows, says Caroline Bourgeois, the curator of the Pinault Collection. “He’s not a believer, but he dared to go to these ancestral questions. He’s leaving behind all the easier ways to speak about you and the world, and not afraid of challenging death.”

Bodies age. Bodies die. Sculptures, sometimes, endure. A decade ago in Venice, before “Boy With Frog” was removed, the Pinault team installed guards and motion detectors around the nude child with the dangling amphibian, and even plopped a Plexiglas box on him at night to keep away vandals. Back then, the sculpture had to remain pristine in order to be perfect.

The “Horse and Rider” now in Paris, though, is being embedded in a more laissez-faire manner. It stands without protection on a busy street, the hooves right on the cobblestones. Pedestrians can inspect the steel of the horse’s mane and the rider’s loafers. It may get a little scuffled, but after 50 years of sculpting, Ray now takes a longer view.

“In two days it’s going to have graffiti. Four days, it’s going to look terrible. In four weeks, the city’s going to demand removal. But I think in 40 years, it’s going to start to look good.”