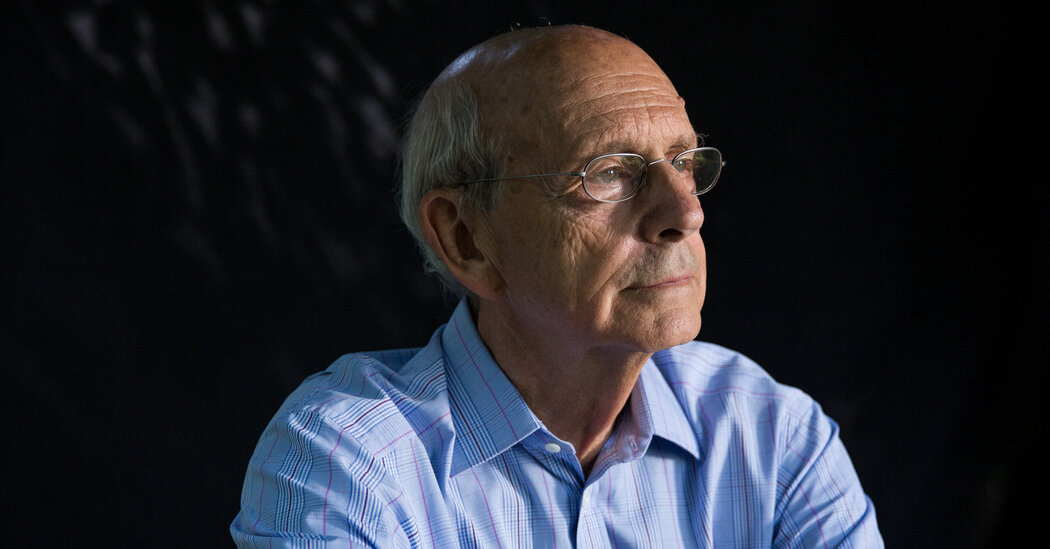

Two misfortunes have befallen Stephen G. Breyer during his long Supreme Court career. One, which became apparent about halfway through his nearly 28-year tenure, was that it was his fate to be the quintessential Enlightenment man in an increasingly unenlightened era at the court. The second happened during this past year: the demand from the left that he step down and open his seat for President Biden to fill.

Justice Breyer’s belief in the power of facts, evidence and expertise was out of step in a postfactual age. The protections of the Voting Rights Act were no longer necessary in the South? The Constitution’s framers meant to give the populace an individual right to own a gun? Or, more recently, the federal agency charged with protecting American workers was likely powerless to protect the workplace from a deadly pandemic?

Really? Of course, Justice Breyer was on the losing side.

To my second point, it’s not that requests for him to step down were unreasonable. It’s that they became so vociferous, so belittling, really. It’s as if this distinguished public servant could be shoved out of the way, obscuring any idea of who he is and what his time on the court has meant. That is a loss not only for him — and he certainly deserves better — but also for the rest of us, because his career has much to teach us about the state of the court today.

At 83, Justice Breyer is a decade older than the next oldest justice, Clarence Thomas, and a generation older than the youngest, Amy Coney Barrett, who turns 50 on Friday. Like five of his colleagues (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Barrett, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh), he was once a Supreme Court law clerk.

But there is a difference. He clerked for Justice Arthur Goldberg during the Supreme Court’s heroic age, the period under Chief Justice Earl Warren when the court seemed to be pushing — or dragging — post-World War II America into recognizing the equality of the races and the rights of criminal suspects. The other five came of age in the subsequent era of judicial retrenchment, that era now reaching a climax.

Although the labels often affixed to Justice Breyer are “pragmatist” and “seeker of compromise,” it has always seemed to me that these, while not inaccurate, miss the mark. They discount the passion beneath the man’s cool and urbane persona, passion that I think stems from his early encounter with a court that understood the Constitution as an engine of progress.

That passion was obvious in his astonishing 21-minute oral dissent from the bench in 2007 from a school integration decision that, early in Chief Justice Roberts’s tenure, marked a significant turn away from the court’s commitment to ending segregation. The law professor Lani Guinier, in a famous article in The Harvard Law Review the next year, celebrated that dissent as “demosprudence,” a way of speaking law directly to the people in the expectation that they will then speak back to the lawmakers.

What will work and life look like after the pandemic?

-

Is the answer to a fuller life working less?

Jonathan Malesic argues that your job, or lack of one, doesn’t define your human worth. -

What do we lose when we lose the office?

William D. Cohan, a former investment banker, wonders how the next generation will learn and grow professionally. -

How can we reduce unnecessary meetings?

Priya Parker explores why structuring our time is more complicated than ever. -

You’ll probably have fewer friends after the pandemic. Is that normal?

Kate Murphy, the author of “You’re Not Listening,” asks whether your kid’s soccer teammate’s parents were really the friends you needed.

His passion was obvious this month, too, when the court heard a challenge to the Biden administration’s Covid vaccination rule for businesses employing 100 or more people. Justice Breyer radiated fury as he addressed Scott A. Keller, the lawyer representing the business plaintiffs.

“I mean, there were three-quarters of a million new cases yesterday,” the justice said, his voice rising. “New cases. Nearly three-quarters — 700-and-some-odd thousand, OK?” He continued that the number was 10 times as high as when the Occupational Safety and Health Administration “put this rule in. The hospitals are today, yesterday, full, almost to the point of the maximum they’ve ever been in this disease, OK?”

Noting that the standard for granting an injunction of the sort the plaintiffs requested required a showing that the court’s intervention was in the public interest, he asked: “Is that what you’re doing now, to say it’s in the public interest in this situation to stop this vaccination rule, with nearly a million people — let me not exaggerate — nearly three-quarters of a million people, new cases every day? I mean, to me, I would find that unbelievable.”

Of course, that’s what the court did, and of course, Justice Breyer dissented.

His dissenting opinion, written with Justices Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, wasn’t particularly showy. It was, one might say, Breyeresque, using data, logic and the language of administrative law — a subject he taught for many years at Harvard Law School — to arrive at its central argument:

Underlying everything else in this dispute is a single, simple question: Who decides how much protection, and of what kind, American workers need from Covid-19? An agency with expertise in workplace health and safety, acting as Congress and the president authorized? Or a court, lacking any knowledge of how to safeguard workplaces and insulated from responsibility for any damage it causes?

That this argument failed to carry the day speaks volumes not only about how out of step Justice Breyer is with the court’s trajectory but also how out of step the majority is with the kind of fact-based analysis that he has brought to the problems the court is charged with solving.

In recent months, Justice Breyer has been mocked on the left for clinging to a romantic vision of the Supreme Court as an institution apart from politics. Surely, that argument has gone, if he could only get over that fiction and understand the political moment, he would hang up his robe.

That mistakes the man. He cut his eyeteeth in politics, working for Senator Edward Kennedy as chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee. I’m sure he, along with the rest of us, has watched with clear eyes and a heavy heart as politics swamped the institution he loves.

His understanding of politics — that the only way to make a difference is by staying in the game — led him to stay on the court as the diminished liberal side’s senior associate justice, a role that will now pass to Justice Sotomayor. Although he will reportedly remain on the court until the end of this term, he chose to announce his plan to retire now, just after the court finished assembling the cases it will hear and decide through late June or early July. This suggests he has the months ahead fully in view and has decided that he has made all the difference he can make.

Now it’s time to let someone else try.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.