Every person on Earth shares in the quest that the giant observatory will now begin.

On Monday, NASA announced that the James Webb Space Telescope had reached the perch from which it could spend as much as 20 years in surveillance of the cosmos. It traveled about a million miles since launching on Dec. 25, and what a journey that has been.

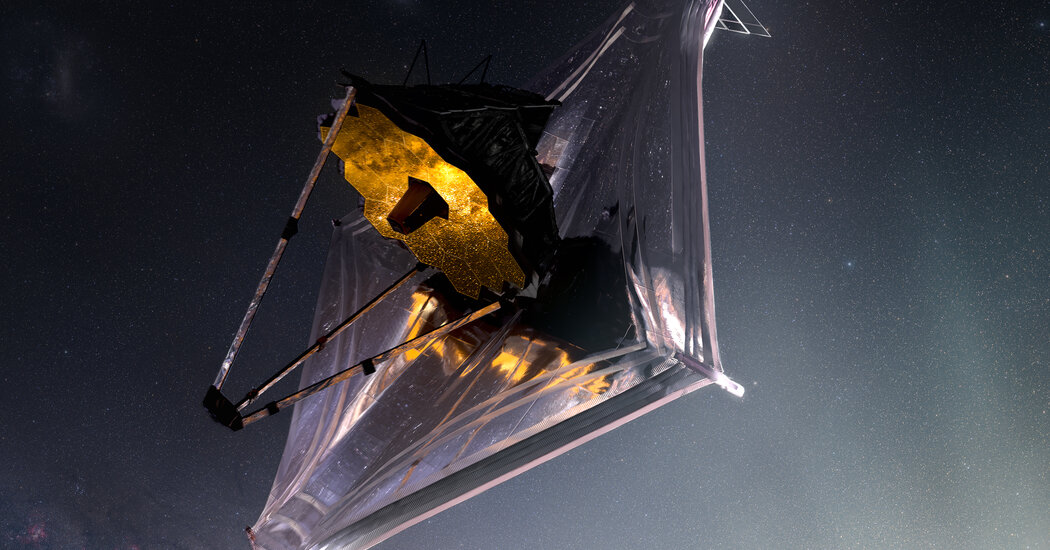

The telescope was launched from French Guiana as a tightly wrapped package of wires, plastic and slabs of gold-plated beryllium. As it journeyed toward its destination, it had to unfold like a robot from the “Transformers” movies and shape-shift into, well, a telescope with a golden 21-foot-wide mirror gliding atop a silver sunshield.

There were 344 things that could have gone wrong during that month — what NASA calls “single point failures” — that would have doomed the mission.

The astronomers were on the edge of their seats.

And so were I and my colleagues. We knew that at any moment a call or a tweet saying something on the telescope had snagged or ripped or frozen, gone offline or just started sending gibberish would plunge us into a heartbroken crisis investigation: Interviewing disappointed and baffled astrophysicists, begging engineers for better explanations about tiny bits of metal or computer algorithms we’d never heard of, covering rounds of commissions, tiger team reports, congressional hearings and outside critics.

Everything about the Webb would be up for grabs: What shortcuts were taken during the decades of effort, by whom? Who had an idea or a suspicion that was ignored? What was the road not taken?

At the risk of jinxing the whole thing, not to mention my journalistic objectivity, I have to say I’m glad it didn’t happen that way. NASA did what it had to do.

And we as humans, temporary inhabitants of a dust mote, as Carl Sagan said, did what we had to do. The Webb telescope is designed to ferret out the very first stars and galaxies that lit up the foggy aftermath of the Big Bang and initiated the grand crescendo of evolution that produced us, among other things, as well as to search for clues to whether the conditions might be right for other creatures’ emergence, on nearby exoplanets.

There was no military or economic advantage in devoting 25 years and $10 billion of national treasure to build a telescope, of all things, devoted not to looking down at our enemies, but out across time and space, trying to decipher the nature and condition of our origins. We all share the quest even if we all don’t get the time and chance to obsess about it.

It’s not just Einstein’s universe, it’s ours too. Our crib and our crypt.

The Webb telescope is now parked in an orbit of L2, a region balanced between the gravity of the sun and Earth, and it will be months before astronomers share the spacecraft’s first images. And it could all still go bad. A tiny uncharted space rock could crash through its sunshield; a solar storm could fritz it; sensitive machinery could break. My very words could jinx it.

In case of failure, everything could still be up for grabs, I believe, except the decision to build such a telescope in the first case. Building it required the best of humans: cooperation and devotion to knowledge, daring and humility, respect for nature and our own ignorance, and the grit to keep picking up the pieces from failure and start again. And again.

“This is unbelievable. We’re about 600,000 miles from Earth, and we actually have a telescope,” Bill Ochs, Webb’s project manager at the Goddard Space Flight Center, said when the telescope finally unfolded its golden wings earlier this month.

We stagger upward under the weight of our knowledge of our own mortality. In the face of the ultimate abyss that is destiny, we can find honor and dignity in the fact that we played the cosmic game to win, trying to know and feel as much as we can in the brief centuries allotted to us.

Once, long ago in another lifetime, I happened to sit next to Riccardo Giacconi, one of the great captains of Big Science and later to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics, on a flight to a conference we were both attending in San Diego. At the time he was with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and looking forward to the launch of his dream project, a satellite — later named the Einstein Observatory — that would record images of X-rays from violent objects like black holes.

Dr. Giacconi, however, had proposed naming his satellite Pequod, after the doomed ship Ahab had commanded in pursuit of Moby Dick, much to the amusement and bafflement of his colleagues.

So I asked him why he wanted to name his dream creation after a doomed whaler.

Dr. Giacconi replied that he liked the connection of the whaling story to New England. Then he began a disquisition about Dante, of all people. During the poet’s tour of hell in the Inferno section of the “Divine Comedy,” he finds Odysseus being consumed by flames, as punishment for his sins, schemes and scams during the Trojan War and subsequent wandering trip back home.

Odysseus tells the story of his life and voyages, how he got back to Ithaca but was then bored and set off with his men on a voyage through the Pillars of Hercules into the great unknown western sea. When his crew got nervous and wanted to turn back, he told them to buck up.

“Consider the seed from which you sprang,” Dr. Giacconi intoned. “You were not made to love like brutes, but to pursue virtue and knowledge.”

Then a great storm rises up and sinks them.

“The search for knowledge does not always end happily,” Dr. Giacconi laughed.

Onward anyway.