He was jailed multiple times in the South during the 1960s and made human rights his lifelong cause, following the Jewish doctrine of “tikkun olam” — to repair the world.

Israel S. Dresner, a New Jersey rabbi who ventured into the Deep South in the 1960s to champion civil rights, befriended the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and was jailed multiple times for demonstrating against racial segregation, died on Jan. 13 in Wayne, N.J. He was 92.

His death, at a senior living center, was caused by colon cancer, his son, Avi, said.

By the time Rabbi Dresner joined the civil rights movement, he was already a veteran of political protests, having been arrested at 18 in 1947 outside the British Empire Building at Rockefeller Center in Manhattan in a protest against Britain’s refusal to let the Exodus, a ship loaded with Holocaust survivors, land in British-controlled Palestine, an incident that inspired the novel of the same name by Leon Uris in 1958 and a subsequent film.

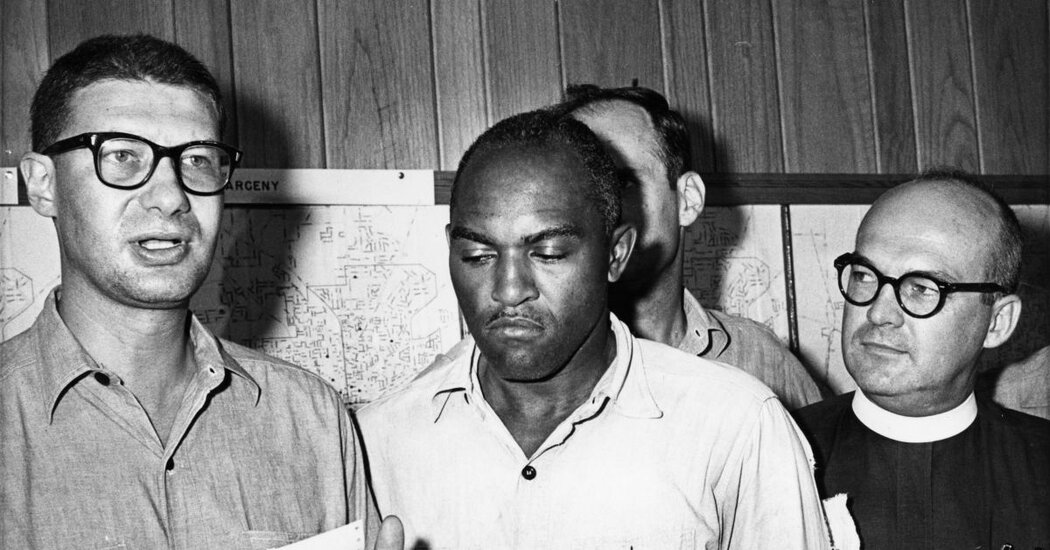

In 1961, as part of the first Interfaith Clergy Freedom Ride to the South, Rabbi Dresner and nine others, known as “the Tallahassee Ten,” were charged with unlawful assembly in trying to integrate an airport restaurant in Tallahassee, Fla.

They were released on bond following their convictions and, with Rabbi Dresner as the lead plaintiff, pursued appeals all the way to the United States Supreme Court, which remanded the case to the Florida courts. He and the others then returned to Florida to serve brief jail terms.

In 1962, in Albany, Ga., he was booked in what was described as the nation’s largest mass arrest of religious leaders, during a march demanding desegregation. It was there that he first met Dr. King, shaking hands through the bars of the cell in which Dr. King, too, had been jailed with hundreds of other protesters.

In 1964, Rabbi Dresner led 16 fellow clergymen, including other rabbis, in a protest outside a segregated motel in St. Augustine, Fla. During the demonstration, five Black protesters plunged into the whites-only swimming pool and were clubbed by the police.

“We came as Jews who remember the millions of faceless people who stood quietly, watching the smoke rise from Hitler’s crematoria,” the rabbis said after their arrest. “We came because we know that, second only to silence, the greatest danger to man is loss of faith in man’s capacity to act.”

Dr. King wrote to Rabbi Dresner that year, saying: “It is your valiant act that touches the conscience of Americans of good will. Your example is a judgment and an inspiration to each of us.”

In 1965, at Dr. King’s behest, Rabbi Dresner delivered a prayer in Selma, Ala., two days after marchers were brutally attacked by law-enforcement authorities in what was immortalized as Bloody Sunday as the protesters tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge on their way to Montgomery, the state capital, to demand voting rights.

Dr. King reciprocated by preaching twice at Rabbi Dresner’s synagogue, Temple Sha’arey Shalom, in Springfield, N.J.

All told, Rabbi Dresner was convicted in three civil rights cases, his son said. His last arrest came in 1980 outside the South African consulate in New York City in a protest against apartheid.

In 2015, he told the St. Augustine Record that Jewish doctrine had persuaded him to follow his conscience to take action in the cause of civil rights with the conviction “that racism and slavery in America was wrong, and segregation in America was wrong.”

After he received a colon cancer diagnosis, he told NPR late last year, “I feel a little guilty leaving the present world where the forces of hatred and discrimination seem to be on the rise and democracy seems to be in danger.”

He was able, at least, to complete his personal agenda, his son said. He visited the graves of his parents and grandparents with his children, went to a Broadway show (“The Book of Mormon”), attended services at Central Synagogue in Manhattan, and ate a pastrami on rye at Katz’s delicatessen on the Lower East Side.

Israel Seymour Dresner (known as Sy, or Si) was born on April 22, 1929, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to immigrants from Eastern Europe. The family moved to Borough Park in Brooklyn, where his father, Abe, owned a delicatessen not far from Ebbets Field. His mother, Rose (Sternchos) Dresner, was a homemaker.

After going to Orthodox Jewish schools and graduating from New Utrecht High School in Brooklyn, he went to Brooklyn College, attended the Habonim Institute to become an organizer for the Labor Zionist Youth Movement and earned a master’s degree in international relations from the University of Chicago in 1950.

He hitchhiked through Europe and was working on a kibbutz in the Negev Desert when he learned in a telegram from his mother that he had been drafted. He served in the Army from 1952 to 1954 in Indiana, where he became a chaplain’s assistant.

Rabbi Dresner was in his mid-20s when, in 1954, he enrolled at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform rabbinical seminary in Manhattan. He was ordained in 1961.

“I think becoming a rabbi was his way to meld his Orthodox education and background with his Zionist political activism and passion for social justice,” Avi Dresner said of his father.

Israel Dresner served as a student rabbi to a congregation in Danbury, Conn., and then to the Reform congregation Temple Sha’arey Shalom in Springfield from 1958 to 1960, after which he became its first full-time rabbi.

His marriage to Toby Silverman ended in divorce in 1991. In addition to his son, he is survived by their daughter, Tamar; his sisters, Phyllis Meiner and Eileen Dresner; and two grandchildren.

His son served in the Israeli Defense Forces, and his daughter volunteered on a kibbutz in Israel. They are producing a documentary called “The Rabbi and the Reverend,” about their father’s role in the civil rights movement and his relationship with Dr. King.

Rabbi Dresner was an early supporter of Soviet Jewry, opposed the war in Vietnam and supported the rights of the poor, women, immigrants, religious and ethnic minorities, disabled people, and gay men and lesbians. He was president of the Education Fund for Israeli Civil Rights and Peace (now Partners for Progressive Israel) and favored a two-state solution to the Palestinian conflict.

He was honored by President Barack Obama at the White House on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, which he attended. While he remained an optimist about race relations, told NPR, “we have a long way to go.”

He retired as a rabbi in 1996 but never quit being a public citizen. His last public protest, in Trenton, N.J., was on Jan. 20, 2017, the day President Donald J. Trump was inaugurated. Rabbi Dresner was 87 at the time.

“A few years ago,” Avi Dresner said, “when I called my dad for one of our twice weekly phone conversations, I asked him how he was doing, and he said, ‘Well, I haven’t lost my sense of righteous indignation, so I guess I’m doing OK.’”

“I think that pretty much tells you everything you need to know about him,” his son added.

Last month, in an interview with WCBS-TV in New York, Rabbi Dresner said, “I want to be remembered as somebody who not only tried to keep the Jewish faith but to invoke the Jewish doctrine from the Talmud, which is called ‘tikkun olam’ — repairing the world — and I hope that I made a little bit of a contribution to making the world a little better place.”