The line between zealous Covid precautions and a mask-optional existence does not run simply between red and blue America, between areas that voted for Joe Biden and those that voted for Donald Trump. As Park MacDougald pointed out in a recent essay for the online magazine UnHerd, if you’re a New York City resident, you can experience two completely different realities just by traveling the short distance from the posher parts of Brooklyn to where he lives in Queens — passing from a world of ubiquitous N95s and careful checking of vaccine cards to a world where masking is maybe a 50 percent proposition and, outside of hipster establishments, the vaccine-pass rules are “almost totally unenforced.”

This is also my experience living in Connecticut. In the Yale-adjacent neighborhoods of New Haven, people seem more careful about masking at the moment than at any other point in the pandemic, more likely to have traded in cloth for the surgical fit. But if you drive just a little ways inland or go out to dinner at a shoreline restaurant or just stroll over to one of New Haven’s poorer neighborhoods, masks diminish and sometimes vanish, and the world often looks almost as it did in January 2020.

Throughout the pandemic, there has been a fear among conservatives and libertarians — as well as the ragged remains of the civil-libertarian left — that the measures adopted to fight Covid would become the basis for a creeping biomedical surveillance regime, a system of public-health restrictions aimed at first at anti-vaxxers but then easily generalized to other forms of behavior deemed unhealthy or antisocial, with something like China’s social credit system the ultimate destination.

In parts of Europe and Australia, the rigor of Covid restrictions and their digitized enforcement has given these fears a certain potency. In the United States, though, since the initial lockdowns faded out in the summer of 2020, what we’ve witnessed is something a bit stranger.

We have a regime of Covid surveillance, but it’s not a general one imposed by a narrow group of technocrats on the great mass of Americans. Rather it’s a regime imposed by the elites upon themselves (and, of course, their service workers), in which the highly educated and highly vaccinated are more likely to carry identity papers and rigorously self-police while less-vaccinated populations in the outer reaches of New York City or the New England suburbs (let alone in Arkansas or Alabama) are often left to their own more casual devices. And to pass back and forth between these two worlds, just a subway ride or short highway drive away from each other, is to appreciate not the ever-expanding influence of Faucian technocracy but, for now at least, the palpable limits of its power.

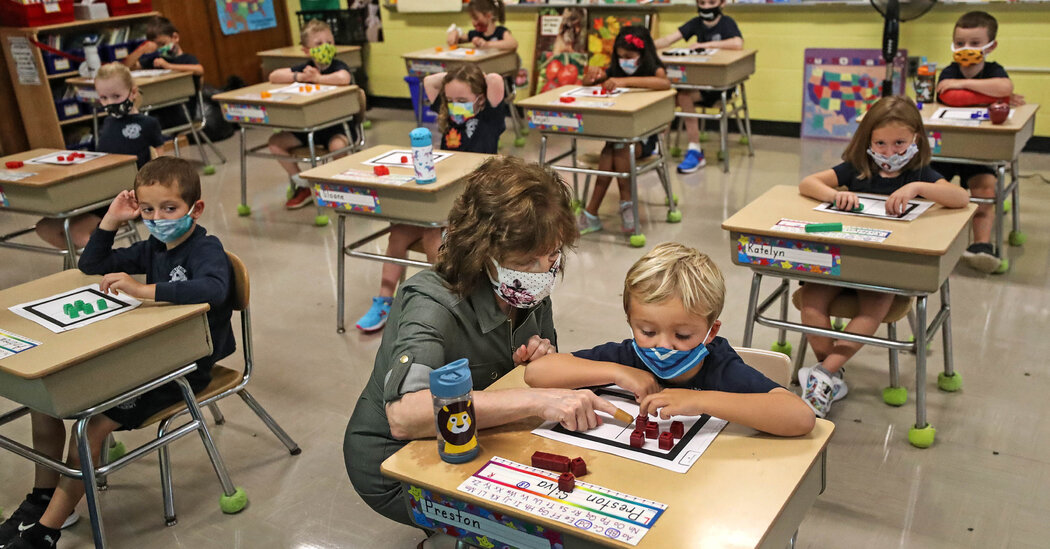

With one crucial exception, of course: public school systems, where statewide school-mask mandates in states like New York and Connecticut have kept kids masked in communities where otherwise the public-health regime has little purchase. Yet because kids are one of the lowest-risk populations, this extension of power only heightens the peculiarity of the entire dynamic: The one place where the professional class can impose its public-health preferences is also the place where it likely makes the least difference.

All this weirdness isn’t just interesting to observe; it’s essential for understanding the landscape of pandemic policy debate as Omicron recedes. In the next few months, one of the crucial divides over Covid policy is likely to be within the Democratic coalition and not just between right and left. And the question of whether and when to relax school masking is likely to be a major flash point, with certain voices (in this newspaper, at The Atlantic, at NPR) already arguing for a relatively rapid exit from the policy while other forces (public health caution, bureaucratic inertia) work to sustain its extension to at least the summer. (And then if another concerning variant crops up, perhaps, to the fall and beyond …)

These conflicts have two important implications. First, they threaten an extension of the dynamics that have already created political problems for Democrats in states like Virginia and New Jersey: the alienation of inner-circle liberalism, with its advanced degrees and N95s, from swing constituencies whose attitude toward the pandemic may be more like “vaccinated and done.”

Second, they threaten an inversion of the scenario feared by conservatives: not the extension of liberalism’s power under the guise of public health but a turning inward of elite institutions and communities, their retreat into a safety-obsessed culture that’s more insular, virtually mediated and unhappier than the society that they aspire to lead.

A cynical Republican politician should probably be rooting for this scenario — a climate of abnormality in the citadels of liberalism that endures even after Covid goes endemic, encouraging normal people to seek their leaders somewhere else.

But as a conservative citizen of liberal America, I devoutly hope my community makes a different choice.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTOpinion) and Instagram.