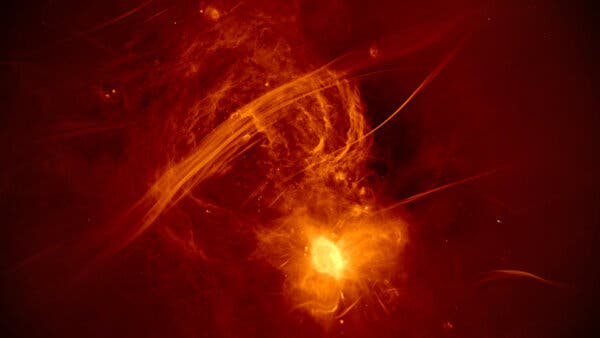

Noise and chaos reign at the heart of the Milky Way, our home galaxy, or so it appears in an astonishing image captured recently by astronomers in South Africa.

The image, taken by the MeerKAT radio telescope, an array of 64 antennas spread across five miles of desert in northern South Africa, reveals a storm of activity in the central region of the Milky Way, with threads of radio emission laced and kinked through space among bubbles of energy. At the very center Sagittarius A*, a well-studied supermassive black hole, emits its own exuberant buzz.

We are accustomed to seeing galaxies, from afar, as soft, glowing eggs of light or as majestic, bejeweled whirlpools. Rarely do we glimpse the roiling beneath the clouds — all the forms of frenzy that a hundred million or so stars can get up to.

The image was captured and analyzed by a team of astronomers led by Ian Heywood of Oxford University and the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. They published their results last week in the Astrophysical Journal.

MeerKAT is a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array, an immense set of antennas planned for construction in South Africa and Australia in the coming decade. When completed, it will be the most powerful radio telescope on Earth for the foreseeable future.

To visible-light telescopes, large sections of the Milky Way sky are rendered black by intervening clouds of cosmic dust. But radio waves pass right through, enabling MeerKAT to get up-close and personal.

“The best telescopes expand our horizons in unexpected ways,” Fernando Camilo, chief scientist at the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory and one of many co-authors of the new paper, said in a news release.

Twenty separate observations, generating 70 terabytes of data and requiring three years of processing, were needed to produce the image. The result is a panorama 1,000 light-years wide and 600 light-years high of the central regions of the Milky Way. (The entire galaxy is 100,000 light years in diameter, and its center is 25,000 light-years from Earth.)

The Milky Way’s disc, where most of the stars and exoplanets reside, appears in the image as a ragged horizontal streak. A dense blob of energy in the middle of the streak marks the spot where lurks a black hole four million times as massive as our sun. The surrounding region is filled with mysterious glowing filaments as much as 100 light-years long.

Astronomers have surmised that such filaments, first recognized 35 years ago, are formed by magnetized tubes of gas and high-energy particles. But scientists still don’t understand how these arose. The new paper, the study’s authors claim, assembled enough new examples of such features to study their properties and varieties as a group for the first time.

Emanating vertically above and below the galactic disc are a matched pair of gigantic radio bubbles, probably the remains of a series of supernova explosions that occurred several million years ago. In the background, the radio image is speckled with the bright dots of supermassive black holes in faraway galaxies.

“I’ve spent a lot of time looking at this image in the process of working on it, and I never get tired of it,” Dr. Heywood said.

Dr. Camilo concurred that the galaxy’s innards resembled an electrical storm. “Electrical activity is of course very much crucial to our living animal hearts,” he added. “I suppose you could say that without electrical activity the center/heart of the galaxy, if not dead, would look very, very different.”