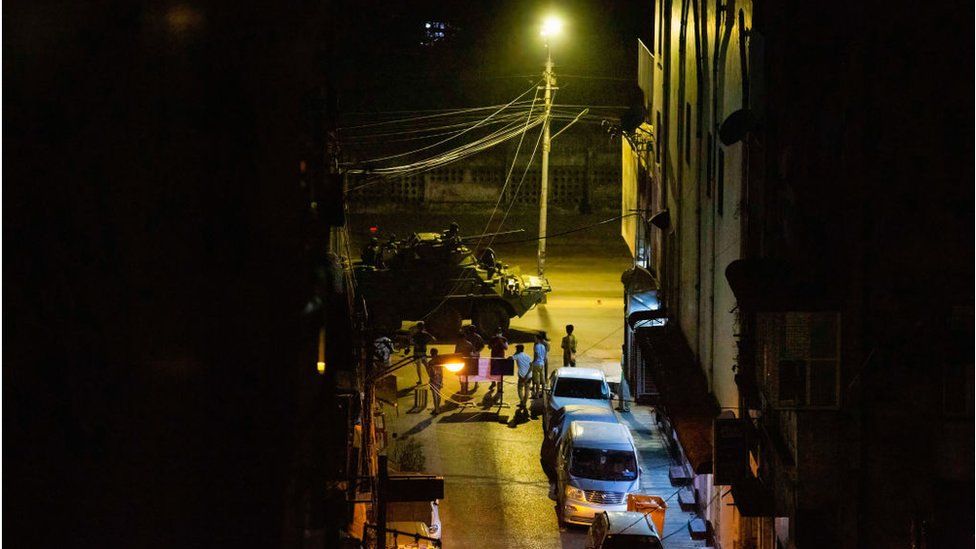

Since it overthrew Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected government in a coup one year ago, Myanmar’s military – known as the Tatmadaw – has gone on to shock the world by killing hundreds of its own civilians, including dozens of children, in a brutal crackdown on protesters.

For Myanmar’s citizens, it has been a year of indiscriminate street killings and bloody village raids. Most recently in December 2021, a BBC investigation discovered the Tatmadaw carried out a series of attacks that involved the torture and mass murder of opponents.

More than 1,500 people have been killed by security forces since the coup in February 2021, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma).

But how did the Tatmadaw become so powerful and why is it so brutal?

What is the Tatmadaw?

Tatmadaw simply means “armed forces” in Burmese, but the name has become synonymous with the current military authority, given its huge power in the country and global notoriety.

For centuries the Burmese monarchy had a standing army, but it was disbanded under British rule.

The Tatmadaw’s roots can be traced back to the Burma Independence Army (BIA), which was founded in 1941 by a group of revolutionaries that included Aung San, regarded by many Burmese as the spiritual “Father of the Nation”. He was Aung San Suu Kyi’s father.

Aung San was assassinated shortly before Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948. But before his death, the BIA had already started to join with other militias to form a national armed force. After independence, it would eventually form what we know today as the Tatmadaw.

Post-independence, it quickly gained power and influence. By 1962, it had seized control of the country in a coup and would rule virtually unopposed for the next 50 years. In 1989, it changed the country’s official name to Myanmar.

It holds an elevated status in the country, and joining the army is an aspirational goal for many, though the coup has left some of its members disillusioned.

“I joined the army because I want to hold a gun, go to frontlines, and fight. I like adventures and the idea of sacrificing for the country,” said Lin Htet Aung*, a former captain in the army.

He quit to join the country’s Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), which sprang up in opposition to the 1 February coup and involves doctors, nurses, trade union workers and many others from different walks of life.

“[But now I] feel very ashamed. I made a mistake about that institution. Peaceful protesters have been brutally attacked, in some cases, with bombs, lethal force and snipers. This is not the Tatmadaw (army) we have expected. That’s why I’ve joined the CDM.”

Embodiment of the country

Myanmar is made up of more than 130 different ethnic groups, with Buddhist Bamars the majority.

Bamars also make up most of the country’s elite – and experts say the army sees itself as the elite of this elite.

With a history deeply intertwined with that of modern Myanmar, the Tatmadaw has styled itself as the founders of the nation and often projects itself as the embodiment of what it means to be truly Burmese.

“They’re very, very steeped in this ultra-nationalist ideology,” says Gwen Robinson, a Myanmar expert at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

“They’ve always seen ethnic minority groups as threats who do not deserve their own patch of Myanmar… as groups who want to upset the unity and stability of the country and that must be eliminated or pacified.”

This has meant that for several decades, Myanmar has been the site of dozens of mini civil wars.

A complex, competing network of armed ethnic militias – all seeking self-determination away from the central Burmese state – has ensured the Tatmadaw is always fighting, often on several fronts at the same time.

In fact, the Burmese army’s near-constant engagement in warfare with these militias is considered by some observers to be the world’s longest-running civil conflict.

“It’s shaped the Tatmadaw into this ruthless fighting machine that will just follow orders robotically,” says Ms Robinson.

Campaign after campaign has made soldiers battle-hardened and, crucially, accustomed to killing within its own borders.

Some ethnic minorities, such as the Rohingya Muslims, have long been subject to some of the army’s worst brutalities. Now, hundreds of protesters, including many Bamar Buddhists, are being killed by their own army.

‘Like a religious cult’

According to Ms Robinson, everybody is a potential insurgent to the Tatmadaw: “They see these protesters as traitors.”

Long periods away on duty, isolated from the rest of society, helps to fuel this view among the soldiers. Some live in cloistered compounds, where they and their families are heavily monitored and fed pro-military propaganda, according to experts and testimony from former officers.

Experts say this cultivates a sense of family among soldiers, and officers’ children sometimes marry the children of other officers.

“The army has been likened to a religious cult,” says Ms Robinson. “They don’t have much contact with outsiders.”

One soldier who later defected to join the Civil Disobedience Movement confirms this.

“These soldiers have been in the military for so long that they know only the language in the army. They don’t understand what’s happening outside the military,” Lieutenant Chan Mya Thu* said.

Also, although the constant warring against Myanmar’s armed ethnic organisations has often been brutal, it’s been extremely profitable for the military.

Carefully managed ceasefire agreements have helped the generals keep control of key resources such as jade, rubies, oil and gas. Profits from these resources – sometimes legal, sometimes illegal – have been a vital source of income for the military for several decades. They also manage large conglomerates with investments in everything from banking to beer and tourism.

Its grip on the economy means not everyone has always opposed the military, with conservative business players aligning themselves with the Tatmadaw despite alleged atrocities.

But years of corruption and economic mismanagement have turned public opinion decisively against the military leadership and towards democratic-style rule under Aung San Suu Kyi, whose National League for Democracy (NLD) has won by landslides in recent elections.

‘State within a state’

Much of the Tatmadaw’s thinking still remains a mystery. “It’s really a state within a state,” says Scot Marciel, who served as US ambassador to Myanmar until 2020.

“They don’t interact with the rest of society. They’re insulated in a giant echo chamber where they’re all telling each other how important they are, how only they can keep the country together, and how without them in power the country would fall apart.”

Critics, for instance, point to how the generals held a lavish military parade and dinner party in the capital city Nay Pyi Taw in March, while troops killed more than 100 civilians across the country in what was one of the deadliest days after the coup.

But lower-ranking soldiers in the military say this camaraderie is very much limited to those in the upper echelons.

“The high-ranking officers are rich and the wealth was never shared with the lower ranks,” Major Hein Thaw Oo*, a former soldier, told BBC Burmese.

“When I joined the Tatmadaw, I thought I was going to guard our borders and sovereignty. Instead I found lower ranks are not valued and are bullied by superiors.”

The soldiers ultimately take their orders from the coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing.

But observers say there is no cult of personality you would usually expect around a military ruler.

“It would be a mistake to think that he specifically is the fundamental problem,” says Mr Marciel. “I think it’s the institution and the culture of the institution that’s the problem, and he’s a product of it.

“Probably more than any other institution I’ve dealt with in my career, there’s just a giant gap between how they see things compared to how pretty much everyone else sees things.”

Major Oo told BBC Burmese that when Gen Hlaing took over he won approval in the forces after upgrading weapons and uniforms.

“But when his term ended, he extended. There were many commanders who are better than him in some aspects, but he refused to stand down. He is the one who broke the rules just for his own benefit,” he said.

Despite this, however, people like Major Oo are the minority – most soldiers support Gen Hlaing and his coup.

Now, more than ever, it appears the Tatmadaw is playing up to its own image – a fighting force that’s secretive, superior and accountable only to itself.

Or as Mr Marciel puts it: “The bottom line is – I don’t think they care very much about what the world thinks.”

Reporting by Nick Marsh and BBC Burmese.

*Names have been changed to protect identities.