The citizens of Virginia have been called to battle. They’ve been shown the enemy. They’ve been armed — not with physical weapons, but with an email address where they can send reports of anything suspicious that they see in their children’s schools, anything they deem disrespectful in their children’s classrooms, anything in a teacher’s or administrator’s conduct that rankles.

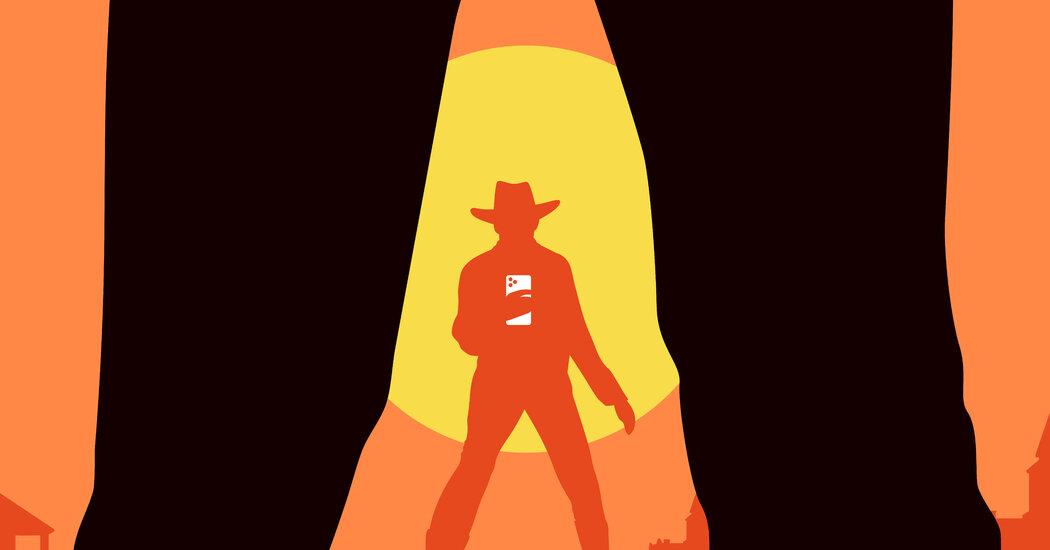

That’s no simple encouragement of greater involvement in their children’s education. It’s a summons to surveillance. It’s a blessing for snitching. Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced the email address — basically, a digital tip line — early last week, vaguely explaining that he was interested in reports of “divisive practices” for cataloging and “rooting out.” His action springs from his pledge, during his campaign for governor, to stop the teaching of critical race theory or anything like it in the state’s public schools, but it’s broader and fuzzier than that. It’s also ripe for abuse.

And it brought to mind the terrible abortion law enacted by state lawmakers and Gov. Greg Abbott last year in Texas, where just about anyone who knows or suspects that a Texan has aided someone in getting an abortion can file a civil lawsuit against that person and, if the suit succeeds, expect at least a $10,000 reward. A person can collect that reward multiple times by identifying abettors of additional abortions. Vigilantism meets bounty hunting meets some nuclear version of political partisanship in a country that needs more prompts for coolheaded civility, not more pushes toward hot-blooded vengeance.

This is scary and wrong. Put aside your position on abortion, about which there are deeply felt differences of opinion and understandable debate, and your interest in public-school pedagogy, which is a subject of legitimate discussion. Is the way to address Americans’ disagreements to transform citizens into snoops and have them turn on one another? Our leaders should point us toward common ground, not add whole new weapons to our battlegrounds. In Virginia and Texas, they added weapons.

In West Virginia, too. Last November, as Donald Trump assiduously sowed doubts about the integrity of American elections, its secretary of state, Mac Warner, announced a “See Something, TEXT Something!” program that created a phone number to which the state’s residents could send text messages about suspicions that a person or people were voting illegally or engaged in voter fraud. It “allows a citizen easy and immediate access to file a confidential complaint,” he said in a written statement about the effort. As with Youngkin’s tip line in Virginia, its potential misuse as a tool for pure harassment and partisan recrimination is enormous.

Does anyone really doubt that the Virginia tip line will receive some complaints from parents who are merely steamed that a teacher was stern with or aloof to their child? Or that the West Virginia phone number will be texted by a few people bothered that neighbors with darker skin head to the same voting site that they visit?

In the decades since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, with our growing awareness of the porous and penetrable boundaries of cyberspace, we have worried plenty — and rightly — about government surveillance, about how easy it can be for unseen actors employed by the state to spy on and meddle with us.

The Virginia, Texas and West Virginia developments suggest another kind of surveillance, born not of technology but of tribalism and so utterly of this acrimonious moment, when so many Americans are so edgily on guard and so eager to point fingers. What we sweepingly and inexactly refer to as cancel culture is, in part, the online aggressiveness of Americans who patrol for transgressions and prosecute the transgressors. And there can be a thin line between holding people accountable because they’ve done clear wrong and mercilessly vilifying them because they have contrary views or expressed themselves clumsily.

We lose sight of it. We cross it. And our leaders are just as lost. They should be uniting us, not inciting us. The latter is all too easy: We’re dangerously riled up as is.

For the Love of Sentences

I somehow hadn’t been aware that Matt Damon was hawking cryptocurrency, but Jody Rosen brought me up to speed in The Times, describing him and a portion of his audience vividly: “Damon offers a particular kind of appeal to that demographic. His star power is based on brains and brawn; he can recite magniloquent phrases while also giving the impression that he could fillet an enemy, Jason Bourne style, armed with only a Bic pen. In the ad, his words are high-flown — all that stuff about history and bravery — but they amount to a macho taunt: If you’re a real man, you’ll buy crypto.” (Thanks to Barbara McDonald of Mill Valley, Calif., for nominating this.)

There’s alliteration that’s strained (I routinely commit that offense) and then there’s alliteration that’s perfect. An example of the latter comes from the science writer Dennis Overbye, remarking in The Times that the universe is “our crib and our crypt.” (Kristin Kenlan, Shelburne, Vt.)

Also in The Times, Matthew Shaer assessed the past and present of a fabled stretch of American coastline: “As recently as the 1890s, the nine-mile barrier island now known as Miami Beach was little more than a fetid tangle of swampland, dominated by the remains of a handful of old coconut and avocado plantations. All had failed spectacularly. The heat was tremendous, the rain torrential, and as for the local fauna, it appeared to consist entirely of violent bugs.” (Susan Kolodin, Bethesda, Md.)

And Caity Weaver had this to say about various male characters in her life who followed the antics of the “Jackass” star Jason Acuña, a.k.a. Wee Man: “What I had perceived to be a richly textured tapestry of manhood woven from unique yarns of individual experience was in fact a bolt of plain fabric made up of a single fiber: ‘Jackass’ fan.” (Carol Dane, Oakland, Calif.)

On the New Zealand website Stuff, Josie Pagani lamented the budget overruns and seemingly interminable wait for a promised road to ease congestion around the city of Wellington: “More work has been accomplished on changing the opening date than laying down blacktop. They could surface the road with print-outs of the excuses.” (Cathy Drummond, Raumati Beach, Paraparaumu, New Zealand)

Reflecting in The Boston Globe on Tom Brady’s long stretch of glory years with the New England Patriots, Dan Shaughnessy wrote: “The 21st century is the High Renaissance of Boston sports, and Brady was our Michelangelo.” (Lauri Mitchell, Hilton Head Island, S.C.)

In The Washington Post, Alexandra Petri had enormous fun skewering Boris Johnson (who is, admittedly, as skewer-able as a kebab), writing that he’s in the midst of “what seems to be his 98th or 99th scandal since arriving in the public eye. One more, I think, and he is entitled to a free haircut.” (Tom Morman, Leipsic, Ohio)

Also in The Washington Post and also on the subject of Johnson, George Will wrote: “With his carefully tousled hair that looks as though his barber used pruning shears, his shambolic manner of an unmade bed walking, and his louche lifestyle, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson — Eton; Balliol College, Oxford University — brings to mind Dolly Parton’s quip ‘You’d be surprised how much it costs to look this cheap.’” (Susan Reigler, Louisville, Ky., and Jeannie MacDonald, Portsmouth, N.H., among others)

To nominate favorite bits of recent writing from The Times or other publications to be mentioned in “For the Love of Sentences,” please email me here, and please include your name and place of residence.

What I’m Reading (and Playing)

-

Sandro Miller’s photos of John Malkovich in The Daily Beast are both a mesmerizing paean to what actors do and a perfect example of what an actor as talented as Malkovich can do. Yes, he uses wigs, accessories and such to turn into Albert Einstein, Che Guevara and others, but nothing proves as crucial as the particular set of his jaw, the temperature of the fire in his eyes, the shifting contours of his elastic face.

-

You stay in the journalism business long enough and it’s easy to forget what you loved best about it in the first place: the hunt for information, the exposure of lies, the challenge of distilling a complicated world, the positive impact of managing to do so. Carl Bernstein’s new memoir, “Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom,” reconnected me to all of that, and gave me the charming sense that when he looks back on his career, it’s not seeing himself played by Dustin Hoffman in “All the President’s Men” or the subsequent decades of adulation that he dwells on. It’s the start. It’s being unjaded and unsated and unproven — and going about the heady work of making a mark and a difference in this crazy, long and too-short life.

-

This article in Air Mail by James Kirchick is a fascinating — and infuriating — examination of a potent, destructive strain of homophobia in the conspiracy theorizing about John F. Kennedy’s assassination.

-

Up until about three weeks ago, I began every day by plucking my smartphone from the night stand and, before I even turned on the light, playing The Times’s Spelling Bee. Then I discovered Wordle, which instantly took its place. I was ludicrously late to the party, but, hey, I finally arrived — more than two weeks before The Times purchased Wordle and with no clue that would happen. I feel like I’m cheating on the Bee, an alphabet adulterer, a phonetic philanderer. So be it.

On a Purr-sonal Note

I go on and on about dogs, but I grew up with as many cats.

The first was Pumpkin, named not only for his orange color but also for when and where we found him: just before Halloween at a farm that was selling gourds about to become jack-o’-lanterns. There was a litter of kittens there, not all of them had been claimed, and Mom was as charmed by them as my siblings and I were. Dad had no say. That was the case with every pet we foisted on him from then on.

After Pumpkin came Nicky and then Sable, a black cat. Sable gave birth and we kept one of the females, Boo. Somewhere along the way — I’m not clear on the precise timeline or overlap — there was also a regal male calico named Cupid, whose purr was louder than the whir of the noisiest kitchen appliance. It was seismic: a four-legged earthquake. How to bring joy to the people around me could be a mystery, but Cupid was easily elated. I just let him onto my lap and stroked the back of his head.

I mention him and Pumpkin and the others partly because of the news last week that the Bidens had welcomed a cat into the White House. But it’s also my way of acknowledging and saying thanks to the many cat lovers who read this newsletter.

From the first time I regaled you with stories about my dog, Regan, to the 100th, you’ve written to me to say that while you’re not dog people, Regan seems pleasant and pretty enough and you’re glad she makes me happy. You haven’t said: When do we cat lovers get our day? You haven’t groused that you just don’t understand those of us who are loopily pooch-struck, even though you may indeed find us baffling. You haven’t argued that I and my dog-loving kind are misguided and that cats are superior. You haven’t turned this into a contest and competition.

Which is to say: You haven’t made this like so much else in American life. And I draw at least a small measure of hope from that.

I realize that I can extrapolate only so far from cats and dogs. I realize that many people love and live with both! (Shall we consider them animal-minded analogues of swing voters?) But on matters zoological or ideological, you can choose to retreat to your corners or to venture out in search of common ground and common courtesy.

No, I’m not telling you to go out and hug a QAnon adherent. I’m not saying you should meet the Jan. 6 rioters halfway. But even in these deranged days of ours, there are people on the side of the aisle opposite from whichever one you inhabit who aren’t unreachable extremists. Figuring out better ways to communicate with them could be what keeps the extremists at bay.

It requires humility. It calls for grace.

And you know who demonstrated both? The unnamed reader whom I chided in last week’s newsletter, the one who emailed me a flippant comment that seemed to suggest that I’d blithely traded my romantic partner for my dog.

He read that reprimand and then sent me this: “Mr. Bruni, I apologize for the mindless and hurtful comments I made that you rightfully took exception to.” Short and sweet. He didn’t try to defend or explain himself. He just said he was sorry.

I wrote back: “I appreciate the apology, ‘accept’ it (whatever that means, never was sure) and thank you for the kind note.” And what I appreciate is not just his apology but also the fact that he may be a kind and decent person who occasionally has a bad day or an uncharitable impulse and who communicates sloppily from time to time. If so, we’re brothers, doing our flawed best to steer around our worst.