BEIJING — Thousands of performers skipped and gyrated on a 125,000-square-foot, high-definition LED stage programmed to resemble a sheet of shimmering ice.

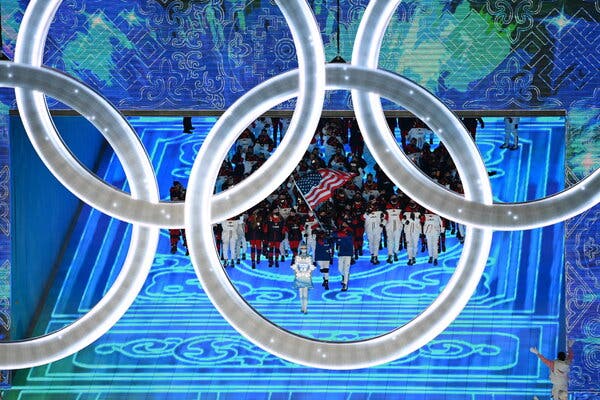

A parade of athletes from 90 countries and territories snaked through them, bundled in puffer jackets and masked because of the pandemic. Together, they waved their mitten-covered hands and national flags toward knots of spectators scattered around the swooping stands of China’s National Stadium.

On a cold Friday night in Beijing, a boisterous, technicolor ceremony brought to a start one of the most logistically complicated, tightly controlled and politically fraught Olympic Games in history. Against this extraordinary backdrop, Beijing officially became the first city to host both a Summer and Winter Olympics.

“Tonight, the Olympic Winter Games Beijing 2022 is opening as scheduled,” said Cai Qi, president of the Beijing organizing committee, “and a long cherished dream is becoming a reality.”

In 2008, in this same building, China had aimed to signal a new open stance toward the global community. What message, then, was this spectacle, this ceremony, these Games, meant to send to the world?

The question had been posed to Thomas Bach, the president of the International Olympic Committee, a German lawyer (and gold medalist fencer) often inclined to speak in winding paragraphs, the night before the ceremony. His response was six words.

“China is a winter sport country,” Bach said.

The answer, in its brevity, its modesty, spoke volumes about the mood that has permeated the Olympic movement through the run-up to these Games. Throughout history, athletes, politicians, fans and commentators have regularly heralded international sports as an arena, symbol and trigger for social change. But in the last six months the I.O.C. — in response to relentless questioning from activists, journalists, athletes and fans — has taken great pains to emphasize how narrow its influence actually was, how little power it actually had to affect the world.

In any context, the Olympics continue to represent a sprawling festival of shared humanity and sports achievement. In a polarized world, few things can bring together so many people from so many corners of the globe.

Explore the Games

- Sports Guide: From Alpine skiing to speedskating, here are all the sports that are part of the Winter Games.

- Olympic Fashion: Our fashion critic reviews the best and worst outfits at the opening ceremony — fedoras and capes included.

- Jumping the Geopolitical Divide: The freeskier Eileen Gu was born in the U.S. but is competing for China. Can she be all things to all people in a fractured world?

- Inside Beijing’s Bubble: Here is our reporter’s journey into a walled-off maze of Covid tests, service robots and anxious humans.

But these may nevertheless end up a Winter Games of limitations, of tempered expectations, of cold pragmatism.

However the evening was interpreted, China had its own message for the sports world, relayed over the course of the two-hour ceremony in the stadium known as the Bird’s Nest.

There were 3,000 performers, far fewer than the 15,000 who appeared at the four-hour ceremony that opened the Summer Games in 2008. They were, according to organizers, “ordinary people,” students of all ages from the Beijing and Hebei provinces.

It was a shorter, simpler, stripped down ceremony, because of both the subfreezing cold and the pandemic, which, despite the pageantry, frosted the proceedings.

The spectators — specially invited, because tickets were not available to the general public — occasionally ignored the guidance of organizers to refrain from cheering to stop the potential spread of the coronavirus.

“The mission of these Olympic Games, like any Olympic Games, is bringing the world together in peaceful competition,” Bach said, “uniting humankind in all our diversity, always building bridges, never, ever erecting walls.”

The irony, to some, will be that no Olympics has ever featured this many walls, in the “bubble” China created to keep out the virus. The walls appear here in all shapes and sizes.

Walls surrounded the National Stadium where the ceremony took place, the athletes’ villages, the venues and the main press center, separating the Games from the city in which they were operating. Tall fences, monitored by guards, ring the many hotels where international journalists and other Olympic participants are spending the next two weeks. Clear partitions even separate people in event dining halls.

The ceremony, in a sense, was an effort to revive some of the communal spirit of the Games.

Athletes from traditional Winter Games powers like Norway, the United States, Russia and Canada marched between first-time nations like Haiti, Saudi Arabia, Uganda and Vietnam.

The flag bearers for the United States were the speedskater Brittany Bowe and the gold medalist curler John Shuster. The bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor had originally been picked to carry the flag, but she tested positive for the coronavirus upon arrival in Beijing and was, like a number of other athletes here, forced into isolation.

“Our hearts go out to the athletes who because of the pandemic cannot make their dreams come true,” Bach said at the ceremony.

The athletes will be competing at a Games that continues to evolve its competitions for the times. The I.O.C. for instance has labored to establish equal representation for men and women at its Games. The percentage of female competitors here will be 45 percent, up from 41 percent at the 2018 Olympics in South Korea.

Still, the mood around these Winter Games, in other ways, has felt lukewarm.

International sponsors and broadcasters, for instance, have tamped down their normal promotions surrounding the Games, playing down the host nation. News outlets around the world, including several from the United States, elected to send stripped down crews or in some cases skipped the Games altogether.

All of this has given off the impression that the Winter Games, in some ways, will be less savored and celebrated than endured.

The I.O.C. can look ahead to its lineup of upcoming host cities: Paris in 2024, Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo in 2026, Los Angeles in 2028.

But first come two weeks of competition in Beijing and its surrounding mountains, where athletes will strive for a feeling of normalcy in highly abnormal times, in a profoundly abnormal setting.

In the closing moments of the ceremony, Bach, in English and Chinese, wished the crowd a happy Lunar New Year. Xi stood, removed his mask, and declared the Games open. The Olympic cauldron was lit.

With a fairly typical burst of music and fireworks, an atypical Olympics was officially underway.