Why are Americans slow to get booster shots?

The United States has a vaccination problem. And it is not just about the relatively large share of Americans who have refused to get a shot. The U.S. also trails many other countries in the share of vaccinated people who have received a booster shot.

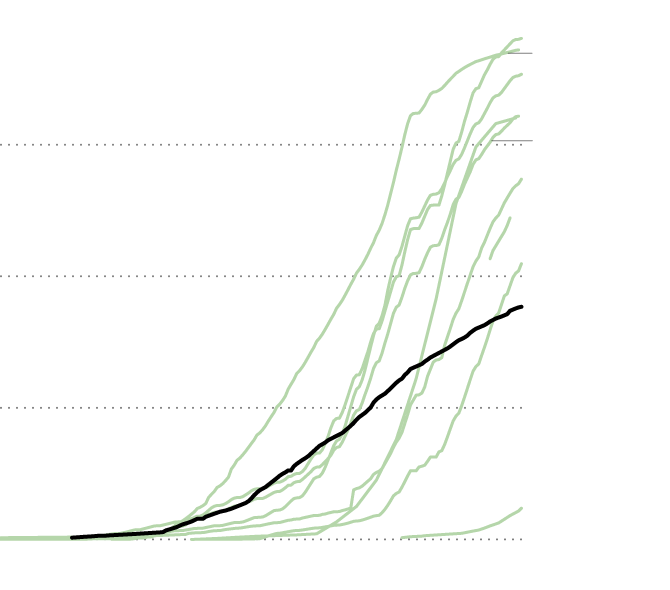

In Canada, Australia and much of Europe, the recent administering of Covid-19 booster shots has been rapid. In the U.S., it has been much slower. Compare the slopes of these lines:

This is a different problem from outright skepticism of the vaccine. The unvaccinated skew heavily Republican, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The vaccinated-but-unboosted more closely resemble the country as a whole. Millions of Americans who have already received two vaccine shots — eagerly, in many cases — have not yet received a follow-up. The unboosted include many Republicans, Democrats and independents and span racial groups.

This booster shortfall is one reason the U.S. has suffered more deaths over the past two months than many other countries, as my colleagues Benjamin Mueller and Eleanor Lutz have explained.

The most urgent problem involves the unboosted elderly. (About 14 percent of Americans over 65 eligible for a booster had not received one as of mid-January, according to Kaiser.) But some younger adults are also getting sick as their vaccine immunity wears off.

A recent study from Israel, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, was clarifying. For both the elderly and people between 40 and 59, severe illness and death were notably lower among the boosted than the merely vaccinated. For adults younger than 40, serious illness was rare in both groups — but even rarer among the boosted: Of the almost two million vaccinated people ages 16 to 39 in the study, 26 of the unboosted got severely ill, compared with only one boosted person.

“Boosters reduce hospitalization across all ages,” Dr. Eric Topol of Scripps Research has said. As Dr. Leana Wen wrote in The Washington Post, “The evidence is clear that it is at least a three-dose vaccine.”

Two explanations

What explains the American booster shortfall? I think there are two main answers, both related to problems with the American health system.

First, medical care in the U.S. is notoriously fragmented. There is neither a centralized record system, as in Taiwan, nor a universal insurance system, as in Canada and Scandinavia, to remind people to get another shot. Many Americans also do not have a regular contact point for their health care.

As a result, preventive care — like a booster shot — often falls through the cracks.

The second problem is one that has also bedeviled other aspects of U.S. Covid response: Government health officials, as well as some experts, struggle to communicate effectively with the hundreds of millions of us who are not experts.

They speak in the language of academia, without recognizing how it confuses people. Rather than clearly explaining the big picture, they emphasize small amounts of uncertainty that are important to scientific research but can be counterproductive during a global emergency. They are cautious to the point of hampering public health.

As an analogy, imagine if a group of engineers surrounded firefighters outside a burning building and started questioning whether they were using the most powerful hoses on the market. The questions might be reasonable in another setting — and pointless if not damaging during a blaze.

A version of this happened early in the pandemic, when experts, including the C.D.C. and the World Health Organization, discouraged widespread mask wearing. They based that stance partly on the absence of research specifically showing that masks reduced the spread of Covid.

But obviously there had not been much research on a brand-new virus. Multiple sources of scientific information did suggest that masks would probably reduce Covid’s spread, much as they reduced the spread of other viruses. Health officials cast aside this evidence.

Tests, vaccines, boosters

Similar problems have occurred since then, especially in the U.S.:

-

Regulators were slow to give formal approval to the Covid vaccines while they waited for more data — even as those same regulators were pleading with people to get shots.

-

Regulators were slow to approve rapid tests — even as Britain and Germany were using rapid tests effectively.

-

U.S. officials were slow to tell people who had received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to get a follow-up shot — even as some experts were persuaded enough by the data to do so themselves.

As a result, Americans were slower to put on masks and slower to be vaccinated than they could have been. The pattern is repeating itself with boosters. Across Europe, Canada and Australia, health officials are urging adults of all ages to receive booster shots. Israel and several other countries are even giving second booster shots to vulnerable people.

In the U.S., some officials and experts continue to raise questions about whether the evidence is strong enough to encourage boosters for younger adults. Two top F.D.A. officials quit partly over the Biden administration’s recommendation of universal boosters. The skeptics say they want to wait for more evidence.

I don’t fully understand why statistical precision seems to be a particularly American obsession. In the case of boosters, political beliefs seem to play a role, as is often the case with Covid debates: Some booster skeptics are bothered that rich countries like the U.S. are giving third shots before many people in poorer countries have received first shots. But discouraging booster shots in the U.S. has not helped increase vaccine uptake abroad.

Officially, the skeptics have lost the debate. President Biden and Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the C.D.C. director, have strongly encouraged all eligible people to get boosted. Still, the expert skepticism does seem to have fueled public skepticism, which in turn has led to fewer booster shots. This chart is based on Kaiser’s most recent poll:

The public skepticism, in turn, is one reason that the U.S. is suffering more Covid hospitalizations and deaths than many other countries.

More on the virus:

-

New Jersey’s Democratic governor will lift the state’s school mask mandate.

-

Republican candidates, wooing Trump voters, are stepping up their attacks on Dr. Anthony Fauci.

-

Ottawa declared a state of emergency as protests against pandemic measures spread across Canada.

-

Another reason the U.S. pandemic response has lagged: a lack of societal trust, Ezra Klein writes.

THE LATEST NEWS

Politics

-

Redistricting could mean that fewer than 40 House seats are competitive, down from 73 a decade ago.

-

Leondra Kruger, a moderate judge, is a potential U.S. Supreme Court nominee. She could be a mediating force in Washington.

The Olympics

-

The American skier and defending champion Mikaela Shiffrin fell and was disqualified from the giant slalom.

-

The Dutch speedskater Ireen Wüst became the first person to win individual golds at five Olympics.

-

The I.O.C. president and Peng Shuai, the Chinese tennis player who largely disappeared from public life, held a private meeting.

Other Big Stories

-

Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, will visit Moscow and Kyiv this week, hoping to prevent a war.

-

One SEAL candidate died and another was hospitalized after several days of training known as “Hell Week,” Navy officials said.

-

A butterfly center in Texas has fallen victim to misinformation and outright lies spreading online.

-

A Home Depot worker swapped $387,500 in fake bills over four years, officials say.

Opinions

Gail Collins and Bret Stephens discuss the economy and Jan. 6.

The round-the-clock culture of remote work mostly benefits employers, says Elizabeth Spiers.

Bill McKibben and Akaya Windwood are organizing older Americans for progressive change. Call it “codger power.”

MORNING READS

Soccer: Amid political crises, Africa is finding unity and joy in a tournament.

Computer errors: Tiny chips, big headaches.

Existential dread: Climate change enters the therapy room.

Quiz time: The average score on our latest news quiz was 9.0. Can you do better?

Advice from Wirecutter: The best gear for the big game.

Lives Lived: John Vinocur, a former foreign correspondent for The Times and The Associated Press, reported with equal gusto about Cold War crises in Eastern Europe and the best bouillabaisse in Marseille. He died at 81.

ARTS AND IDEAS

The legacy of ‘Jackass’

There was the time a performer tucked a toy car into his derrière, its tiny metal form visible in an X-ray. Or “the High-Five,” a gag involving a giant hand that smacked unsuspecting cast members. Somehow, over 22 years, the “Jackass” crew hasn’t run out of ideas. In their latest movie, “Jackass Forever,” the pranksters — now middle-aged — up the ante: In one stunt, a performer, restrained in a chair, is coated in honey before a live bear enters the room.

As a show, “Jackass” ran for only three seasons, but it had a significant impact on American pop culture. Four months after the show’s debut in 2000, its ringleader, Johnny Knoxville, was on the cover of Rolling Stone.

You can see the DNA of “Jackass” in later TV hits, like the celebrity prank show “Punk’d” — so ubiquitous it became a verb — and the game show “Wipeout,” in which contestants hurdle through cartoonish obstacle courses. YouTube brought about “a new generation of would-be Jackasses, who could upload their antics straight to viewers,” Hannah Woodhead writes at the BBC.

Still, one element separates “Jackass” from its imitators, Amy Nicholson writes in The Times. It’s the group’s friendship, “which is evident as they egg on the wounded and apply a healing salve of applause in nearly every scene,” she writes. “Bones get brittle. The heart muscle remains strong.” — Sanam Yar, a Morning writer

PLAY, WATCH, EAT

What to Cook

A tangy ginger-scallion sauce brightens this nourishing Korean porridge.

What to Watch

“The Worst Person in the World,” starring the Norwegian actress Renate Reinsve, is a funny-sad story of a woman on the verge of figuring herself out.

What to Read

Take a nostalgia trip with Chuck Klosterman’s “The Nineties,” which examines the decade’s sports, politics and culture.

Now Time to Play

The pangram from Sunday’s Spelling Bee was hydrant. Here is today’s puzzle — or you can play online.

Here’s today’s Mini Crossword, and a clue: In a way (five letters).

If you’re in the mood to play more, find all our games here.

Thanks for spending part of your morning with The Times. See you tomorrow. — David

P.S. The Times has started a reporting project on the monitoring of employee productivity. If you know about examples, we want to hear from you.

Here’s today’s front page.

“The Daily” is about George Floyd. On the Book Review podcast, Ruta Sepetys and Jami Attenberg discuss their new books.

Claire Moses, Ian Prasad Philbrick, Tom Wright-Piersanti, Ashley Wu and Sanam Yar contributed to The Morning. You can reach the team at themorning@nytimes.com.