The Alaska Supreme Court recently decided a case that an experienced lawyer told the court was “the most significant case since statehood.” The court confirmed that the state’s new primary and ranked-choice voting system — which would eliminate traditional party primaries — is here to stay.

The decision is significant not just for Alaska; it could also have considerable implications nationally. For the reforms in that state, like those that have taken hold in other states and localities across the country, are among the most promising structural solutions that could help mitigate the forces of extremism in our politics.

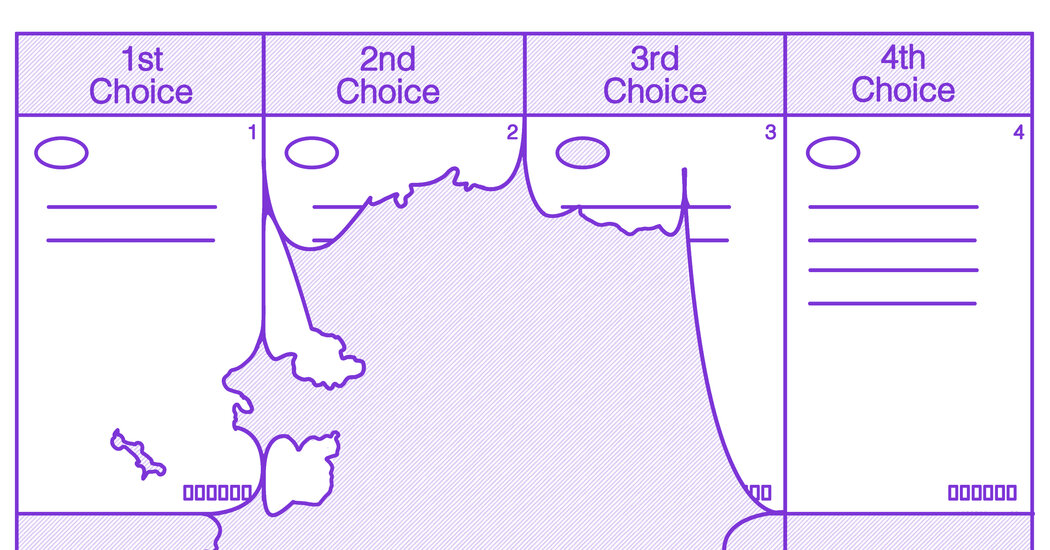

Through a 2020 ballot measure, Alaskan voters enacted a top-four primary. In this system, candidates list themselves on the ballot in three possible ways: as affiliated with a political party or political group, as undeclared or as nonpartisan. The four candidates who get the most votes move on to the general election, in which ranked-choice voting is used to determine the winner. (In ranked-choice voting, rather than selecting just one candidate, voters can instead choose several and rank them.)

This reform aims to increase the likelihood that candidates with the broadest appeal to voters, rather than more factional candidates, will win the election. In a traditional primary, in which many candidates can split the vote, factional candidates can prevail by drawing, say, just 25 percent of the vote. Because factional candidates often hold more extreme views, this reality helps fuel dysfunction in American politics.

In a recent book, “Rejecting Compromise: Legislators’ Fear of Primary Voters,” a group of political scientists found that “legislators believe that primary voters are much more likely to punish them for compromising than general election voters or donors.” Incumbents in safe seats often embrace more extreme positions to avoid facing challengers in primaries. And some moderate incumbents who might have broad appeal in a general election are now retiring rather than competing in primaries they are likely to lose to ideological extremists.

In Alaska, Senator Lisa Murkowski’s re-election campaign this year will provide a test of how much this change to primary elections might reshape our politics. Under traditional rules, she might well not have survived a Republican primary. She voted to convict Donald Trump in his post-Jan. 6, 2021, impeachment trial in the Senate, and Mr. Trump endorsed another, MAGA Republican and vowed to campaign personally against her.

Yet she has owned Alaska’s center since at least 2010 (a year she lost the Republican Senate primary but won in the general election as a write-in candidate), and she was recently endorsed by a Democratic Senate colleague, Joe Manchin of West Virginia. If she retains that broad appeal, her re-election prospects would be strong under the state’s reforms. In the general election, if Ms. Murkowsi is the first choice of many and the second choice of enough independents, Democrats and Republicans, Alaska’s new system will ensure she will be re-elected.

It is possible that other electoral systems might do an even better job of identifying consensus candidates. Some political scientists worry that while the political parties can still loudly endorse, support and campaign for the candidates they prefer in Alaska, that might not be enough to adequately inform voters without the additional party imprimatur that follows from winning a traditional primary.

But all election systems have both advantages and disadvantages. And in our era, one of the highest priorities in election reform must be reducing the influence of extremism in our politics.

Despite all the attention national voting-rights debates receive, most political reform takes place at the state level — especially in states, like Alaska, where voters can bypass legislatures and vote directly on reform. More states, localities and even political parties are adopting alternative forms of voting in an effort to reward candidates with broader electoral appeal.

The political makeup of these areas ranges from blue to purple to red. Signatures in Nevada are now being gathered to qualify a ballot measure for this fall that would create an election system similar to Alaska’s. (That proposal would establish a top-five primary.) In 2021, New York City used ranked-choice voting for its primaries, including the all-important Democratic primary for mayor. Voters in Maine adopted ranked-choice voting, where it has been in effect since 2018 and used for federal elections as well as state primaries. In Utah, 23 cities, including Salt Lake City, are authorized to use ranked-choice voting. To avoid a more factional candidate winning a traditional primary, the Republican Party in Virginia opted to use a nominating convention, with ranked-choice voting, which led to its nomination of Glenn Youngkin for governor.

Given the self-interested resistance of many legislators to changing the rules under which they have been elected, these reforms have their strongest prospect in states and localities with direct-democracy options. In places that permit voter initiatives, voters can enact policy directly. Of the 63 states and localities that have adopted an alternative voting system since 2000, about 40 percent did so through a public vote. Incumbents who believe they have the broadest electoral appeal yet fear being primaried by factional candidates from the extremes should also support reforms like that in Alaska.

Other states would do well to pay attention to whether the reforms in Alaska and other states and cities do a better job of giving candidates with the broadest appeal to voters a good chance to actually get elected.

Richard H. Pildes, a professor at New York University’s School of Law, is the author of the casebook “The Law of Democracy: Legal Structure of the Political Process.” He filed an amicus brief in support of Alaska’s system in the State Supreme Court case.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.