Thousands of men who left their families in Yemen in the 1950s and worked for decades in British factories before returning to their war-torn homeland say they are facing a daily struggle to survive after their UK state pension payments were stopped without explanation.

Amid a seven-year conflict in Yemen and the constant threat of famine and destitution, the men tell BBC News how they have been fighting to get payments reinstated in a scandal likened to the Windrush controversy.

“When I was in Britain I did not ask for benefits or insurance, I relied on my own sweat of my brow and I do not know why this has happened to us.”

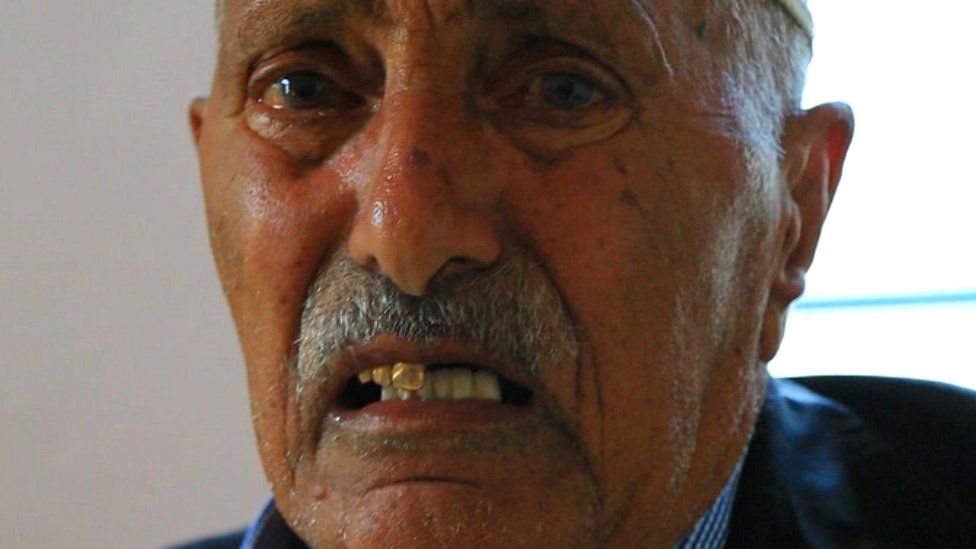

Thabet Muthanna Jubran arrived in Britain in 1967 and began working, like many fellow Yemenis, at Birmingham Small Arms factory in Small Heath, a metal manufacturer producing motorcycles and machine tools based in the heart of the industrial city.

He joined many others grafting in the factories and foundries across the West Midlands who saw the UK as “the mother country” after Yemen first came under British rule in 1839.

But after retiring in Yemen, he said his payments had stopped without warning two years ago and he could not get any answers from the UK government.

He is not alone. It is thought there are about 2,500 men who have not received a penny of their state pension in years – with one man telling the BBC he had been paid nothing in a decade.

The men have spent years trying to find out why. Their former employers are not at fault.

The BBC has discovered it is down to a combination of Yemen’s fragility given the war and the subsequent impact on banking, but also the response by UK government authorities.

“What is my fault that I am without a pension?,” said Mr Jubran.

“They know our situation, especially coronavirus, a war and high prices – what is our crime?

“They are stopping our pension. This [is] Great Britain, the mother of the world.

“Some people have died [waiting for their payments], their widows are very elderly – who will support them, especially now?”

The stoppages could not have happened at a worse time.

The cost of living in Yemen has soared as the war between the failing government and Iran-backed Houthi rebels has escalated, leaving people starving amid the Covid pandemic.

According to the UN, it is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis with 80% in need of aid or protection.

Rice, a staple food in most households, rose in cost by almost 164% from February 2016 to October 2020, the International Rescue Committee reports.

Ragih Muflihi, chief executive of Sandwell Yemeni Association in the West Midlands, which is home to one of the largest communities in the UK, is liaising with more than 50 of the former workers on their cases.

“People who came here to work came to work in the Black Country in the industrial areas, the steelworks.

“A lot of them lost their hearing or lost limbs working 30 to 40 years in factories and they’ve gone back [to Yemen] to live the final part of their lives; and to struggle because they’re not getting their pension is not acceptable really,” he said.

Mr Muflihi estimates the men are owed approximately a minimum of £50 a month and the total amount owed to all is about £500,000.

The introduction of life certificates by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) about six or seven years ago enabling Yemenis to prove they are alive and eligible for payments has still not led to people being paid, he added.

The money they are owed is “life-saving” as inflation rises by 200% and people continue to starve.

“We see it as an equivalent to the Windrush situation. We see this as a pension scandal,” he said.

‘We are here in a war – but we have become lost’

Qasim Saeed Al-Juhouri, from Al-Adad, arrived in Britain in the 1960s. He began working at Blackheath Stamping, in the centre of the industrial Black Country, before taking on jobs at other factories in the West Midlands.

The factory worker returned to his home country but said he had not received any pension payments for 10 years.

He completed a life certificate in September as requested by the DWP as proof he is alive but said he was still waiting.

“I sent them messages and since 2012 my [money] stopped,” he said.

He said he and his wife “have really despaired and we have nothing but God to relive us of our distress”.

“We are here in a war. There is no government in Yemen and no embassy in order to put our cases to them. We have become lost,” he said.

Ahmed Omar Abdullah Al-Yafei feels just as lost. He worked in Wednesbury and at a steelworks in West Bromwich for many years before returning to Yemen.

Previously he received a pension of £82 a month but said he had not had anything for six years.

He completed a life certificate in English and Arabic five years ago and during correspondence with the DWP was told in 2019 some documentation was not valid.

“Now [it’s been] five years I’ve been chasing. I did not receive any response from them [the DWP],” he said.

“The message to Britain – give us our money back.

“Yemen is a mess, [there is] hunger and war, all of which problems are unprecedented – the prices and inflation.

“Where do we go? Where do we go?”

Saeed Abdullah Abdulkarim said he had worked in factories in Britain for 40 years in total and his payments had stopped in 2019.

He recently lost his wife to Covid-19.

“I lost all the money I had in her treatment,” he said, adding he felt like the authorities “are playing us”.

“There are people who have four and five years without pension for any sin,” he said.

“There is no justification, they are all playing with us there.”

John Spellar, Labour MP for Warley in the West Midlands, where many of the men lived and worked, urged the government to “get a grip” of the problem.

“There was a problem with people verifying their existence and, even before the war, you’re dealing with ungoverned space,” he said.

“But it was the utter refusal by the DWP to get a grip of cases when people provided evidence and people are living in severe destitution and we should not underestimate that,” he said.

He added: “The people from Yemen who came to the UK went to the Black Country, the West Midlands and Sheffield and worked in the metal industries which are hot, dusty conditions and they’ve done the UK a service which needs to be recognised.

“A bit like the Windrush situation, the indifference of the Civil Service to try to find a resolution is, well, ministers should just say ‘I want an answer, so what’s going it’s going to be?'”

The Windrush scandal saw thousands of UK residents – most originally from the Caribbean who had been living in the UK for decades – being wrongly classed as illegal immigrants.

Although many of the Yemenis lived and worked in the West Midlands, there are men in Cardiff, Sheffield and Newcastle facing the same issues.

Community leaders across the UK have now jointly written to pensions minister Guy Opperman calling for urgent meetings over the financial stoppages.

Why is there a war in Yemen?

The conflict, which started in about 2014, is between the government and Iran-backed Houthi rebels and has claimed as many as 110,000 lives.

It is seen as a proxy war between Shia Iran and Sunni Saudi Arabia and eight other Sunni Arab states – backed by the US, the UK and France.

There have been bursts of civil unrest in the country for many years, including divisions between the north and south as well as the presence of al-Qaeda and latterly Islamic State.

Despite separatists and the government signing a power-sharing agreement to end the conflict in southern Yemen in 2019, the war continues and shows no signs of abating.

The conflict and a pandemic hitting supply chains has exacerbated problems in a country which already imports about 90% of its food.

Last March, the UK government announced it was cutting aid to a number of countries including Yemen – reducing that country’s by about half to £87m – due the financial impact of the pandemic.

The payment crisis is affecting whole families. Fatima Ahmed Qassem lost her husband two decades ago and said the pension payments had stopped when the war started in Yemen.

She signed a life certificate in September last year and is waiting to hear from the DWP.

“I am suffering and ploughing the land,” she said. “I am a widow for 20 years. My husband went to the UK to work.

“We used to get our wage. He passed on and I would continue to get it until the war began.

“[I] suffer every day and there is no-one to support me or the house.”

Ahmed Alawi Saleh Al-Yafei, who came to Britain in the 60s and worked in Sheffield, West Bromwich and Birmingham, said he had been paid £35 a week until his payments had stopped in about August 2016.

He said he had completed a life certificate as well as other paperwork but had heard nothing.

“We are requesting what is ours,” he said. “We worked in Britain in factories, of course it was hard. We went and did what we had to do and now they cut off what is ours.

“We worked just as hard as anyone from the UK, just like them.

“We were there. We had a lot of free time and they dealt with us in a really nice way and now we are not receiving what is ours and we’ve heard nothing.

“Solicitors send letters… fill in applications and they have not responded.

“We are here to request ‘give us our pension – mine and my wife’s’.”

It is a complex situation in a fragile country made worse by war, but the BBC has been able to reach The National Bank of Yemen, where many of the men have accounts to access their pensions.

Saber Saeed Al Sharmani, manager in foreign relations at the bank, said payments made in sterling to the men from the DWP had stopped in October 2019, affecting 2,489 clients, several hundred more than the DWP has said are affected.

The British Arab Commercial Bank, based in the UK, had been facilitating the payments but notified the National Bank it would be closing its account as the war developed.

The DWP then used another correspondent bank, but that meant switching to Yemen’s currency, rials. Hundreds of claimants protested due to the poor exchange rate in the country.

All payments were stopped in March 2021, the DWP said, when the Yemen bank withdrew the service due to the complaints. But no-one has been able to explain the missing payments that have stretched back up to a decade.

“I can’t explain why some people have not been paid [for many years] – when stoppage was 2019,” Mr Al Sharmani said.

“The war started 2014 and contact with people in Yemen stopped.”

He said the DWP had once been in regular contact with claimants about their proof-of-life certificates but that had also ended without warning.

“We tried to help and tried to email the DWP but got no response,” he said.

Daniel Hinge, assistant editor of Central Banking magazine, said the fragility of the country and it being seen as high-risk could cause issues as money from the UK went through corresponding banks’ “payment corridors”.

“The problem is each step of the way the bank has to do anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism checks on the payments; and for a lot of banks they feel like that’s just too much of a risk.

“It’s very difficult to assess the risks… for a country like Yemen, so they might just simply decline to process the transaction.”

In a statement, the DWP said: “We understand the frustration customers may feel after the Yemini correspondent bank withdrew their services resulting in payments being paused.

“We have now negotiated a solution with the banking providers which will allow us to resume payments, all of which will be backdated.

“We encourage anyone affected to contact us.”

Until the men start receiving their payments again, they will continue to question the British system they worked in which they feel has neglected them.

“My message is that Britain has to look. People wait eight years, 10 years and three years and we get no help, except from God,” Mr Jubran said.

“Is this what the British system is about and how it deals with people? It doesn’t fulfil its law and obligations. We have no way out of this, no alternative.”

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk