Once one of the country’s best young players, he became a top player again after a car crash left him slipping in and out of consciousness.

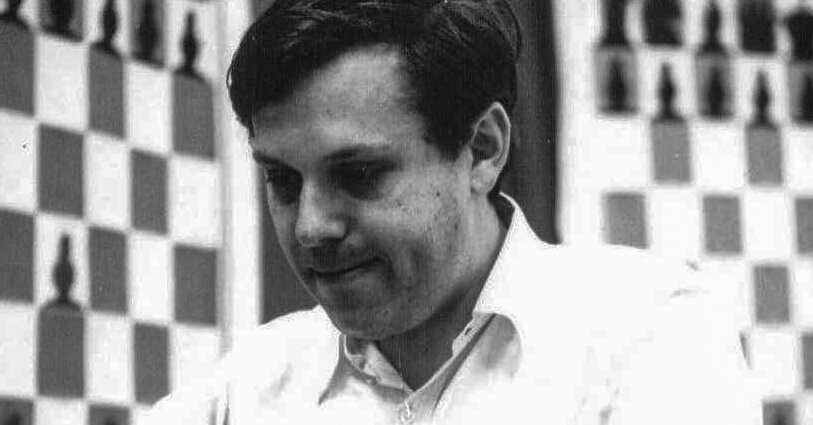

Arthur Feuerstein, who was once one of the best young chess players in the United States, even managing to hold his own against Bobby Fischer, and who survived a horrific head injury to once again become a top player, died on Feb. 2 in Mahwah, N.J. He was 86.

His wife, Alice Feuerstein, said the cause was pancreatic and liver cancer.

Mr. Feuerstein rose through the chess ranks in the 1950s. But after notable results in top-level competition, including in a United States Championship, he turned away from life as a professional player because it was too unstable and too poorly paid. He took the path more traveled, finding work with large companies as a systems analyst, while contenting himself with occasionally playing in tournaments with some of the country’s best.

One day in July 1973, Mr. Feuerstein and his wife left their home in Fort Lee, N.J., and headed for the weekend to their small vacation house in the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania. They had not gone far when an 18-wheel truck in an oncoming lane slammed on its brakes to avoid hitting a car in front of it and jackknifed slightly into the lane in which the Feuersteins were driving.

In seconds, the top of their car was torn off. Something slammed into Mr. Feuerstein’s head and also killed the Feuersteins’ beagle, which was with Alice in the back seat. Alice’s back was broken; she was in an upper body cast for six weeks.

Mr. Feuerstein was in worse shape. He slipped into and out of consciousness, with a breathing tube down his throat. The neurosurgeon in charge of his case told Alice that the prognosis was not good, that he would quite likely never be able to speak or walk and would need constant care.

Then one day Mr. Feuerstein woke up, pulled the breathing tube out and began trying to talk. A nurse called Alice, who rushed to the hospital. She found him playing chess with the neurosurgeon, who had also been called.

Years later, in a profile that appeared in 2012 in Chess Life, the magazine of the United States Chess Federation, the game’s governing body, Alice Feuerstein said her husband, after waking, did not even know what a toothbrush was. But, Mr. Feuerstein recalled, “I remembered everything about chess, even my openings.” He also recalled that he had won that game with the doctor.

Mr. Feuerstein spent the next few years in intensive physical and speech therapy, but he never fully recovered. He was able to work only sporadically and relied on disability insurance for most of the rest of his life. But he did return to competition at something approaching his pre-accident ability, sometimes beating grandmasters, and he remained a master-level player into his late 70s.

He played his last tournament in October 2015, when he was nearly 80, and scored 50 percent, with one win, one loss and a draw.

Arthur William Feuerstein was born on Dec. 20, 1935, in the Bronx. He was the third child of Benjamin and Sidonie (Abraham) Feuerstein, who immigrated from Hungary in 1919 and owned and ran a small grocery.

It was out of a desire to be closer to his brother, Harry, who was 16 years older, that Mr. Feuerstein learned chess when he was 14; he had seen his brother playing with friends.

He became enthralled with the game. He quickly organized a chess club at William Howard Taft High School in the Bronx and began challenging other schools to matches. After graduating in 1953, he went to Baruch College in Manhattan, where he received a degree in business. All the while he competed in local tournaments.

It was a golden age for the game in the United States, particularly in New York City, which fostered a generation of future stars. Among them were William Lombardy, who won the world junior championship in 1957 with the only perfect score in the tournament’s history; the Byrne brothers, one of whom, Robert, later became a contender for the world championship and the chess columnist for The New York Times; and Bobby Fischer, the most prodigious talent of all.

Mr. Feuerstein might have been lost or overwhelmed in such company, but he held his own.

At the 1956 United States Junior Championship, he took third, behind Mr. Fischer. He then edged Mr. Fischer for the United States Junior Blitz Championship, in which each player had five minutes for the entire game.

The third Rosenwald tournament, played in October 1956 at the Manhattan Chess Club, is usually remembered because of Mr. Fischer’s remarkable win against Donald Byrne, Robert’s younger brother. But Mr. Fischer finished in a tie for eighth, while Mr. Feuerstein was third — just behind Arthur Bisguier, another New York prodigy, who had won the United States Championship two years earlier.

Then, in the 1957-58 championship, Mr. Feuerstein tied for sixth with Arnold Denker, a former champion, and Edmar Mednis, a future grandmaster. Mr. Fischer, who was then only 14, won the championship, beating Mr. Feuerstein in the process for the first and only time. Over his career, Mr. Feuerstein had a record of one win, one loss and three draws with Mr. Fischer.

Having established his credentials in elite competitions, Mr. Feuerstein was selected to represent the United States in the World Student Team championship in 1957, in Reykjavik, Iceland, and again in 1958, in Varna, Bulgaria. The U.S. finished fifth in 1957 and sixth in 1958.

It was during the second trip that he met 17-year-old Alice Rapprich, who lived in Prague but was on vacation in Bulgaria. After returning to the United States, Mr. Feuerstein joined the Army and asked to be stationed in Europe. He was posted to Heidelberg, Germany, where he wooed Ms. Rapprich, persuading her to marry him in 1960.

Around that time, he played in the first U.S. Armed Forces Championship. He tied for first.

The Feuersteins lived in Paris for two years. They returned to the United States in 1962, moving into a four-story walk-up in Brooklyn. Mr. Feuerstein found work at Honeywell and then at Sun Chemical, where he was working at the time of the accident.

He also became reacquainted with his old chess adversaries and colleagues, including Mr. Fischer, with whom he had always been friendly. But when Mr. Fischer found out that Mr. Feuerstein was married, he was incredulous, believing that being married would severely affect his chess-playing ability. It was the beginning of the end of their friendship.

Even as a part-time player, Mr. Feuerstein continued to be widely respected. He competed in the 1972 United States Championship, an invitation-only event, and won the 1971 Championship of the Manhattan Chess Club, one of the country’s oldest and strongest clubs.

Ten years after the accident, the Feuersteins had a son, Erik. In addition to his wife, Mr. Feuerstein is survived by his son, two grandchildren and his sister, Lillian.

Mrs. Feuerstein said that although her husband loved chess, it was still surprising that he could play at an elite level after the accident, because he needed help in so many day-to-day chores. The accident also permanently impaired his short-term memory, which is an essential skill for playing the game.

“He didn’t know what he had for breakfast,” she said. “If you asked him one hour after, he couldn’t tell you.”