What are the choices in life that shape our happiness, our self-worth, our sense that we’ve grown up and evolved past the model provided by our parents? What about the ways others treat us, and the ways we treat ourselves, that leave us feeling uncertain, exhausted, lonely? What success do we believe we can achieve — and what success do we believe we deserve?

For our new focus group by Times Opinion, we decided to explore some of these ideas in our pressure-filled era, by listening to women about the shifts they’ve seen and felt in work life, careers, relationships, parenting and gender roles in recent years.

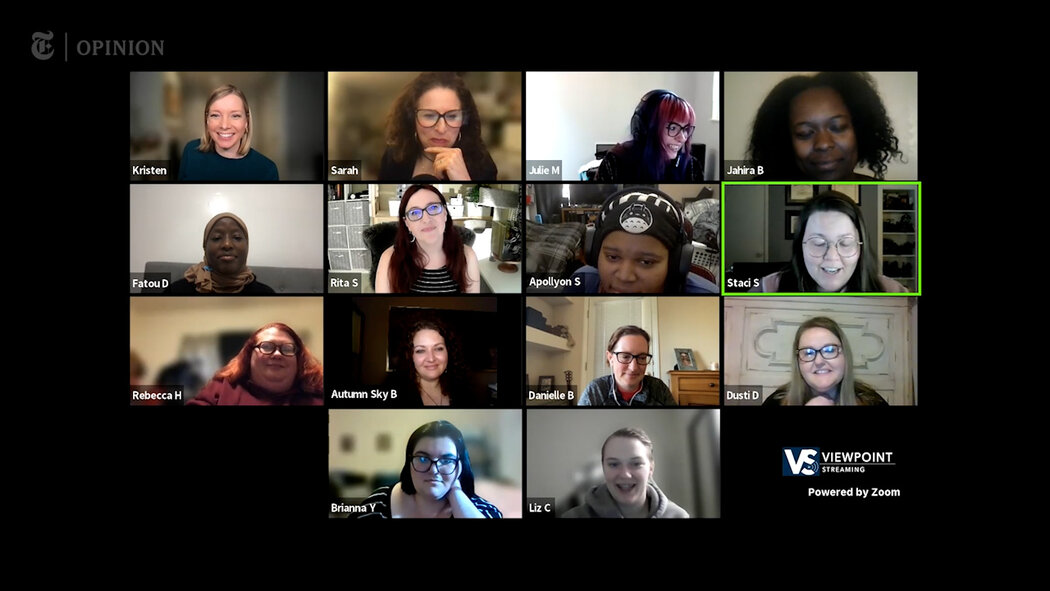

The members of the group, ages 22 to 43, are married and unmarried, partnered and unpartnered, mothers and avowed never-mothers. Eleven are cis-gendered and one identified as a woman and nonbinary. They ran the gamut in work experience and politics (six Biden supporters, four Trump supporters, and two who were for “someone else” in 2020). Those differences aside, all of them saw gender as a defining aspect of their lives. Several had seen men leap ahead of them at work, yet were also deeply skeptical of movements aiming to help women like #MeToo. Mothers, they all agreed, bore the brunt of the practicalities regarding child care, as well as the expectations of caregiving. That, in turn, had led more than one woman to decide parenting was not in their future.

The conversation, moderated by focus group veteran Kristen Soltis Anderson, was frank and personal. Younger participants were, for the most part, opting to delay or forgo parenthood and marriage, often seeing those choices more in the framework of constraint and burden rather than as happy life-cycle events. Many of the women were making different decisions — and seeing their options as more expansive — than those of their mothers.

This is the fifth group in our series, America in Focus, which seeks to hear and understand the opinions of wider cross-sections of Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity; an audio recording and video clips of the session are also included.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: If you had to pick one word to describe how you are feeling these days, what would that word be?

Autumn Sky (36, white, community health coordinator from Nebraska): Thinly spread.

Brianna (22, white, teacher from Florida): Impatient.

Jahira (26, Black, social worker from New York): Existing.

Danielle (43, white, human resources representative from Nevada): Exhausted.

Staci (32, white, school counselor from Texas): Conflicted. There’s a lot of great things that have happened in my life, like having my 2-year-old son. But then I’m worried about the future.

Jahira: I’m a recent grad, so I’m trying to overcome the impostor syndrome, trying to not think about too much of the future, but trying not to think too much of the past. So really just taking it day by day and not being too hard on myself.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: OK. We’re going to do this same kind of word exercise where I throw out a phrase and then you return a word that comes to mind. The first is, “getting a job.”

Staci: Exciting. Well, genuinely, the first word that came to mind for me was money, which is exciting. But in the current position that I’m in, I’m not making good money. And so I’m like, oh, another job, maybe I could make better money.

Dusti (33, white, substitute teacher from Tennessee): I taught third grade for seven years. And since I had my daughter, I have been staying home. It’s scary when you hear “getting a job” because I know what I made back then, and it wasn’t very much as a teacher. And it’s like: Do I want to go back to making nothing and your whole life is given up to education? Or do I want to focus on something where I’ll make more money and have more family time, but then I don’t have the passion?

Kristen Soltis Anderson: All right. The next big life event or decision, “becoming a parent.”

Julie (30, white, insurance salesperson from Oregon): Never.

Staci: The best. I love it. I am at home every day with my child. He is so funny and so cute and literally everything he does — he wipes his snot on my shirt, and I’m like oh my god, stop. You’re precious.

Rebecca (42, white, unemployed, from Oklahoma): I feel like I neglect her so much sometimes. Because I know she wants so many things, but I just don’t have time to sit and do what she wants all the time. And I don’t know. It’s like it’s not enough hours in the day anymore.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: Brianna, what word comes to mind when I say, becoming a parent?

Brianna: Scary. I’m a preschool teacher. I see the stress that the parents go through, especially in these times, and having to leave work for a week because their children are in quarantine, like, back to back to back. I don’t know if I could do it myself, especially not in this economy.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: Do you think there are differences in how men and women think about big life events or decisions?

Autumn Sky: It’s amazing to talk to men and realize some of them really don’t think that there is a difference when it comes to your career. I have friends who’ve had to go back to work at two weeks, when your body is still recovering from a C-section, or a traumatic birth, or even just a regular birth. And we know from research that women typically fare worse economically after a divorce. And most people I know — if a kid is sick while you’re at work, the mom goes and takes the time to pick them up from day care. As a woman, I think you really have to try to compromise a lot in your life in order to, quote unquote, “have it all.” We get asked, how are you going to handle that, in a way that men don’t.

Julie: I run a community on Discord for women, and so I have a lot of interaction with girls from all over the world. One of the reasons I will say “never” with parenting is because I think men take that entire process, including pregnancy and birth, so much more lightly than women do. Even hearing guys talk casually — really great guys that I know and respect and love — and they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I had to help with the kids today.” Like, but that’s called parenting. Like, you don’t help, you know? I feel very strongly about the fact that they don’t have the slightest clue of how these things impact us as it does to them.

Staci: My husband and I talk about it openly and honestly, and he has seen the light, I guess I would say. I mean, he helps — we’re 50-50. I don’t think I could do it otherwise, and I don’t think that is the norm. So I feel very lucky.

How 12 American Women See Gender Roles at Work and Home Today

Rebecca: My daughter is not my boyfriend’s biological child. We have been together for about four years, and she’s about to turn 8. I do everything. I get up at 5 o’clock in the morning to get her up for school, feed her breakfast, get her off to school. And then, while she’s at school, I have time for myself to do stuff I need to do to the house or whatever. When she’s home, he doesn’t help her with anything.

Liz (26, white, salesperson from New Jersey): I just want to play a little bit of devil’s advocate. My dad and my mom divorced when I was 5. She met my stepdad when I was, like, 7, and I grew up with him. And I think because of the way you asked the question, can it be 50-50? — it can. My stepdad did so much. He pitched in with money for things that he didn’t have to. I was not his kid. He took us on vacations, because he cared about us and my mom and wanted that relationship.

Sarah Wildman: I’m curious — when you hear the word, husband, what comes to mind?

Danielle: Partner.

Rebecca: Companion.

Staci: My best friend.

Liz: Yeah, I thought, like, teammate, partner.

Autumn Sky: Unnecessary.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: Tell us a little bit more about that.

Autumn Sky: I’ve been divorced 10 years. I find that I have a very fulfilling life without having a husband. And I feel a lot of pressure. I live in the Midwest, where it’s very nuclear family, and I feel like all of my friends and family are always saying, well, when are you going to get married. Or, you need a husband. But most of the time, they don’t seem the happiest having a husband. Also, not every woman wants a husband. Some of us want a wife or something outside of a husband. So maybe unnecessary — maybe “not necessary” is a better word.

Sarah Wildman: What about the word, wife, then?

Rita (43, white, grants and contracts specialist from Maryland): I think, supporter.

Liz: I actually kind of think of the same word, like, partner or teammate.

Brianna: Cheerleader.

Sarah Wildman: How do same-sex marriages compare to heterosexual marriages, in terms of equal partnerships? Do you see a difference?

Apollyon (23, Black, unemployed, from Maryland): I think there’s definitely more of a demand for an equal partnership or an expectation of an equal partnership in a same-sex marriage.

Autumn Sky: Sometimes I feel a little bit better understood by women partners, less time explaining what I mean.

Julie: One thing I’ll say — and it sucks. For “husband,” the word “provider” comes to mind. For “wife,” the word “subservient” comes to mind. And when someone says “partner,” it has such a better feeling for me. It probably has a lot to do with how I was raised. My parents are both from the South, so I mean, it’s very gendered. I’d rather say, “my partner,” than “my husband” or “my boyfriend.” I just think taking gender out of it makes it feel better.

Sarah Wildman: Back in 1990, two-thirds of Americans between the ages of 25 and 54 were married, but by 2019, that number was barely half. Why do you think that number has gone down so much?

Staci: I have a lot of friends that are just waiting a lot longer to get married. Everyone’s waiting till they’re financially stable, til they really meet someone who is a good partner. Same thing with having kids.

Fatou (28, Black, chemist from Pennsylvania): I think nowadays women do want to get married. But it’s men that are hesitant to, I guess, commit to anyone, for the most part.

Danielle: When I was in my 20s, all of my friends were getting married and starting families. It was just the next logical thing at that time. And now, I have two kids who are in their 20s, and nobody they know is getting married, and nobody that they know is interested in starting families. Many of them don’t even really have stable jobs or have any long-term plans. And I feel like the whole idea of what it means to be an adult is shifted. It’s just different than it was 25 years ago, when I was looking at marriage, than it is now for people who are in their 20s. The whole paradigm has shifted.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: How do you think through the decision about whether or not to become a mom?

Julie: It all comes down to how I want to live my life, right? My cat doesn’t allow me to go on vacations whenever I want. Thinking about having to work out the logistics of a child turns me off to it completely. And that is pretty much the only reason. Like, I just care about myself more than — I don’t want to care about someone else’s well-being. I want to only care about my well-being and my partner, you know, but I come first.

Rita: I turned 40 immediately after I got married. And we just went through this whole situation trying to decide, are we going to become parents or not. There wasn’t a lot of time left. I think it’s probably the hardest decision that I’ve ever had to make, even more so than getting married. Because starting a new life is bigger.

But it would have taken a lot of effort with fertility clinics, and I didn’t have the motivation in me to carry me as far as I needed to go in order to go that route. And in the end, I ended up having to have a hysterectomy because of other health problems. It closed the door in a way that was comfortable for me and for my husband, because we still believe that we have the opportunity to nurture people and teach people and, in a way, be the type of people that can invest in younger people and pass on what we have learned in our lives.

Apollyon: I’m 23 years old. I know I never want to have children. I’ve always kind of known that. My parents never had anything when I was a child. I would never want to do that to someone. I’m a lot more stable, luckily, and I have a lot more of an understanding of myself. And I also identify as nonbinary, so I have kind of a different perspective on it.

It’s such a shame, because it is kind of that negative thing that I always hear about hysterectomies. But I’ve always wanted one since I was 16, and that’s just kind of due to a history of sexual abuse. And I felt like I don’t want to have the power to have a child. That seems like way too much power for me to ever have. Maybe that’s because I am young. Maybe I’d come to understand it differently if I were older, or I ever had a position where I felt like I wanted a child or needed a child. But I pretty much am a child, so I guess I can just keep myself, and that’s enough for me.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: Do you think that society has different expectations for moms versus dads?

Brianna: As a preschool teacher, I can say, definitely. When you have a sick kid, our first instinct is, hey, call Mom. And it’s sort of sad that’s embedded in our society. Like, Mom is the first line of defense. But I think it’s from experience, too. Like, Dad can’t get off work, Dad is working farther away from home, and Mom makes the decision to pick a child care that’s close to her work in case she has to get out and take care of the kid. I think women are expected to take the brunt of it from the moment they’re carrying the kid to the time they’re 18 and it’s time to move them out — if that happens.

Dusti: When I say, oh, I’m a stay-at-home mom, they think, oh, your husband, he’s the provider. And in financial means, yes, but I mean, this house wouldn’t keep itself up if it wasn’t for us or for moms, you know, and moms who do stay home and work. I feel like it could be changing, based on single dads. Somehow, I’m on single-dad TikTok lately. I’m just seeing all these dads that are wonderful at everything. But it’s not like my dad wasn’t ever home. My dad was the room dad, and my mom worked, because my dad worked weird hours. But it was still: Call Mom.

Sarah Wildman: I’m curious if the idea of mom has changed from the time you were a child.

Julie: Yeah, I mean, I was home-schooled. My dad went out and worked. My mom stayed home. She home-schooled me. Her job was to take care of me and cook and make sure the house worked. She’s the best, you know. Now I’m 30 and I have friends who are moms, and I’m watching them work and also co-parent with men who are not there, and just seeing them stressed out. I don’t know — and this sounds terrible to say, but as I’ve grown, thinking about what a mom looks like, it just seems a lot more stressful.

Liz: So me and my mom didn’t have a good relationship until I was about to graduate college. She spent most of her time with my stepdad or at work. Sometimes I’m like, well, I could be a better mom than that. I can raise a child better to have more confidence. I don’t know if anybody’s seen that dad on TikTok where his daughter’s a gymnast, or does like cheerleading stunts, and he just boosts her confidence like crazy. That’s the kind of parenting I would want to do.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: Do women have a harder time getting ahead in the work force, compared to men?

Brianna: In my type of work, it’s female-dominated — there’s a lot of women in preschool and just teaching in general. It’s not that women don’t have the opportunities, but sometimes women are conditioned to feel like they shouldn’t be as confident or they shouldn’t be as assertive in the workplace as men. I feel like if women felt like they had that permission to be like that, without treading on other people or hurting feelings, that they could be just as successful without all the barriers.

Apollyon: It definitely does depend on the area or the work force that you’re in. I recently worked with my partner. He’s a man, and we were working in the exact same business. They ended up giving him a raise almost immediately after I’d left, after refusing to give me anything despite the fact that I’d worked for them for, I think, double the time that he’d been there.

Danielle: I’ve passed up on promotions and pay increases many times since I’ve been a parent. Throughout my career, I felt like I’m failing either at work or I’m failing at home. It’s hard to have that balance where I’m succeeding at both, and I’ve made the choice time and time again that I want to do better at home than at work. And I know that I could make more, and I could be more successful, and I could be more competitive in the workplace, but I’ve chosen not to be, because I want to have more time with my family. I know a lot of women that that’s the case for. They made a choice to not advance, because they don’t want the additional hours, the more time away from home and more responsibilities, the calls in the evenings, things like that. It’s a pressure for women that most men don’t experience.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: A few years ago, the #MeToo movement changed the conversation about how women are treated by men and specifically in the workplace. What comes to mind for you when I say, #MeToo? Do you think the #MeToo movement was a net-positive for women in the work force, or maybe not so much?

Apollyon: It doesn’t affect the majority, which is the people who are right at the bottom. I don’t think that there’s too much that the hashtag can do. I guess there is the idea of, speak up and have your voice heard. But there’s a lot of people who can’t speak up and can’t have their voices heard. At the end of the day, it doesn’t have a needle-moving effect, and I think it kind of spits in the face of like intersectionality and things like that.

Brianna: Most of the MeToo hashtags I’ve seen have been celebrities or people in high-up positions — high-profile people. But I just think of the negative parts that I’ve heard, even from people in my own family, like men saying, oh, now I could never go to this work function with a woman, because what if she accuses me? And I feel like it’s just brought out some misogyny that might not have been there previously, and also created some apprehension. I think some people are genuinely afraid that their friendliness is going to be taken as inappropriate.

Autumn Sky: While #MeToo might have had some very positive things, I think there were some negative aspects in terms of a woman’s ability to rise within a company. A lot of the executives are men, and I have been amazed how many men said they will no longer consider women for these positions, because they don’t want to be put in a position where a woman will accuse them. Because for the most part, they weren’t believing these stories were true. They were believing that women were using them to get ahead.

Staci: I feel like most people personally, obviously, want victims to be able to be believed and to have their story shared and for their perpetrators to face justice. But unfortunately the #MeToo movement was another thing that was so culturally divisive. I still hear people use #MeToo as a joke, even though it is such a serious topic.

Julie: It’s been a net-positive. I’m more confident speaking up for myself if I don’t feel like something’s fair or if I’m being mistreated. I feel it’s comforting to know I can reference the #MeToo movement when I’m telling some guy, hey, like, that was really inappropriate to say. I know that there’s like all these women that have also spoken up and said the same thing, I felt empowered.

Kristen Soltis Anderson: I want to ask about the word, “feminist.” Show of hands first — how many of you would say that you think the label, “feminist,” would apply to you, that you are comfortable saying, “I am a feminist?”

Julie, Staci, Rebecca, Autumn Sky and Liz raise their hands.

Julie: A couple of years ago, I would have been ashamed to say that I was a feminist, because of the negative connotations around it. I just thought it could have been just a bunch of whiny bitches, like, trying to toot their own horn. But the older I’ve grown and the more I’ve been exposed, I just have realized it’s just about treating women as people. And that doesn’t happen a lot.

Brianna: I wouldn’t feel comfortable labeling myself without some lengthy explanation of what I mean by that. So often, when you say the word, feminist, it triggers so many different things in a lot of people.

Sarah Wildman: Is there anything you think the government should do to better ensure that women and men are paid equally for the same work?

Staci: Provide child care.

Liz: I think that companies should have to put what the salary is on the job application. When you go to apply for a position, I think it should have the amount or at least a range.

Sarah Wildman: What do you think about the idea of actually mandating pay transparency?

Autumn Sky: I actually would go even further to not just say what the position has when you’re applying for it, but what you’re actually paying your employees. Because if you’re embarrassed that you’re paying some people horribly, maybe you’ll change your ways. Lots of times I figured out, because I’m a talker, ‘Oh, you’re getting paid $5,000 less than I am.’ ‘You’re getting paid $10,000, and we’re all doing the same job.’ And so I think it would be great if there was more transparency required at all levels.

Jahira: This is what I’m experiencing now. You would think going to school for six years for a master’s would be enough. So I feel you should let me know how much I would make, because you’re asking more of me, but you’re trying to give me the bare minimum. I just feel like a lot is expected of us. Trying to find a job in itself is exhausting.

This 90-minute discussion, part of Times Opinion’s America in Focus series, was held over Zoom. The participants were selected by the moderator, Kristen Soltis Anderson, with guidance from Times Opinion. (Times Opinion paid her for the work; she does similar work for political candidates, parties and special interest groups.) The participants provided their ages, race or ethnicity and job background. As is customary with focus groups, the last names of participants are not included.

Sarah Wildman is a staff editor and writer in Opinion. Adrian J. Rivera contributed to this article.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.