Whether you call it a correction or a panic attack, a stock market that was already becoming shaky has been roiled by Russia’s hostilities toward Ukraine.

The U.S. stock market has been stumbling since the beginning of the year. Now, Russia’s escalating conflict with Ukraine is adding considerably to the market’s problems.

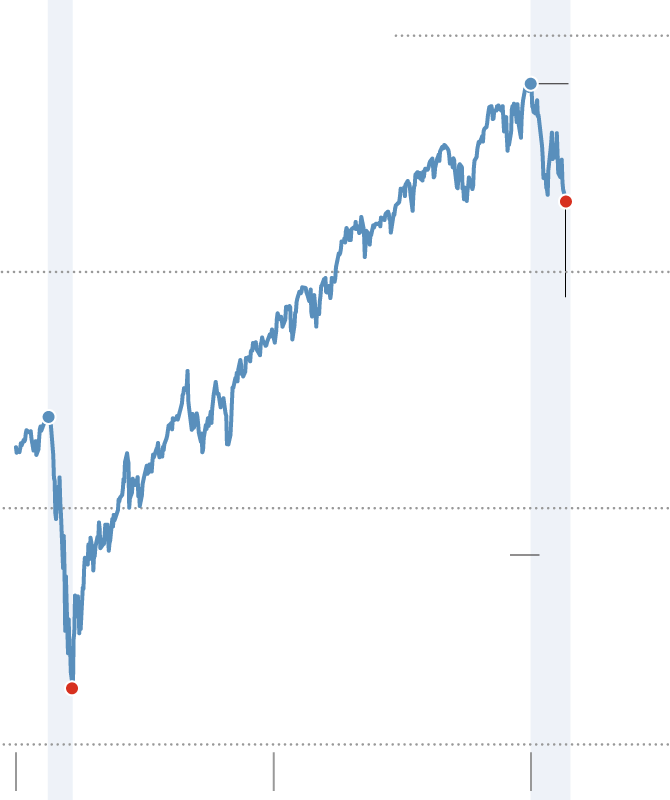

After President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia ordered troops to enter two separatist-controlled enclaves in Ukraine, the S&P 500, which often serves as a proxy for the U.S. stock market, also crossed a notable threshold.

By the market close on Tuesday, the S&P 500 fell to 4,304.76, down 1.01 percent for the day. That wasn’t much of a loss. Yet that incremental decline nonetheless represented a notable milestone. It brought the stock market down 10.3 percent from its most recent peak on Jan. 3.

In Wall Street jargon, that meant the S&P 500 had a “correction,” because its losses since Jan. 3 exceeded 10 percent.

That 10 percent definition is entirely arbitrary and the subject of many quibbles, but this much is clear: A correction is not a good thing.

“It’s an early warning indicator that tells you the market isn’t heading in the direction you want it to be going in,” said Edward Yardeni, an independent Wall Street economist who has compiled detailed records on modern stock market history. “A 10 percent decline isn’t that bad in itself, necessarily, but if the market keeps heading down, the next thing you know, you’re down 20 percent and then by common agreement you’re in a bear market, and, maybe, worrying about a recession.”

What makes the market decline disconcerting is that an escalating geopolitical conflict in Eastern Europe is now being added to the stock market’s ample woes.

Stocks have been falling for weeks, for a variety of reasons. Concerns about the prospect of rising interest rates and generally tighter monetary policy from the Federal Reserve are at the top of my personal list.

The Fed is, perhaps belatedly, planning at its meeting on March 15-16 to start increasing its benchmark funds rate from its current near-zero level, and then to begin reducing its $8.9 trillion balance sheet. All that is intended to mitigate the inflation that is running at an annual rate of 7.5 percent, a 40-year high.

In addition, the death, illness and inconvenience caused by the coronavirus pandemic have had myriad pernicious effects. The labor force in the United States is smaller than it would be otherwise, and the economy’s service sector hasn’t fully rebounded. The pandemic has also caused supply chain bottlenecks that have held back sales and production and increased the prices of important products as varied as automobiles and kitchen appliances.

Many publicly traded companies are circumventing these problems and passing the associated costs on to consumers, but their ability to keep doing so, while generating the profits that fuel the stock market, is questionable.

The Russia-Ukraine crisis threatens to make matters worse for the economy and the markets. Russia produces important commodities, like palladium, which is needed in the catalytic converters of gasoline-powered automobiles, and whose prices have contributed to the high inflation in the United States.

The anticipation of interruptions in commodity supplies has increased prices in futures markets, particularly for oil and natural gas, all of which could go much higher if the Ukraine crisis intensifies and if Western sanctions begin to bite.

For those who remember the 1970s and early 1980s, an era of soaring inflation and multiple recessions caused in part by a geopolitical shift and two oil shocks, the possibility of a 2020s parallel is deeply disturbing.

So is the fact that Russia is a nuclear power engaging in aggressive action against an independent country that is supported by NATO. The possibility that the conflict could be the start of a new Cold War, or something even worse, can’t be totally dismissed.

That said, for investors, it’s worth remembering that since the stock market hit bottom in March 2020, the S&P 500 rose 114.4 percent through Jan. 3. Compared with that stupendous increase, the market’s decline since then has been inconsequential.

5,000

S&P 500

Since the beginning of the

coronavirus pandemic

Peak:

1/3/’22

4,000

Tuesday

Down 10.3%

Prepandemic

peak

From the peak

3,000

Correction

Previous correction

down 33.9%

2,000

2020

2021

2022

5,000

Peak:

Jan. 3, 2022

S&P 500

Since the beginning of the

coronavirus pandemic

4,000

Tuesday

Down 10.3%

From the peak

Prepandemic peak

3,000

Correction

Previous correction

down 33.9%

2,000

2020

2021

2022

5,000

Peak:

Jan. 3, 2022

S&P 500

Since the beginning of the

coronavirus pandemic

4,000

Tuesday

Down 10.3%

Prepandemic

peak

From the peak

3,000

Correction

Previous correction

down 33.9%

2,000

2020

2021

2022

What’s more, although just about everyone who closely follows the stock market agrees that it has had a correction, there is no agreement on when it took place. Laszlo Birinyi, who began analyzing the market with Salomon Brothers back in 1976, says a correction happens whenever the market crosses the 10 percent border, whether it’s at the end of the trading day or in the middle of it.

That’s why Mr. Birinyi, who heads his own independent stock market research firm, Birinyi Associates, in Westport, Conn., says a market correction occurred on Jan. 24, not on Tuesday. The market at one point on Jan. 24 dropped as far as 12 percent below its close on Jan. 3 before rebounding smartly. “The psychology of the market, the mood, shifted then,” Mr. Birinyi said. “People were panicky until then — and then they weren’t.”

The market has moved sideways since then, and has now dropped a bit further. In purely financial terms, that decline, in itself, isn’t a big deal, in his estimation.

Mr. Birinyi focuses on picking individual stocks, not on market averages, and says he doesn’t let such minor things as market corrections affect his strategy.

“We don’t focus on 10 percent increases when the market is on its way up,” he said. “We wouldn’t sell stocks just because there’s been a 10 percent gain. And it doesn’t really matter if there’s a 10 percent decline, either.”

For his part, Mr. Yardeni says he views Jan. 24 as a psychologically important moment, too. It represented “a capitulation in the markets” — a juncture at which many investors simply gave up and sold their shares, allowing the market momentum to shift as bargain seekers began to bid up stocks.

Mr. Yardeni labels episodes like these as “panic attacks” and says Jan. 24 was the end of the 73rd such attack since the start of a long bull market in 2009. The Russian hostilities and the stock market decline on Tuesday probably represented the 74th attack. “There’s no science here,” he said. “It’s totally subjective.”

Investors panic easily, he said, but they will be better off, most of the time, if they just hang on. “I don’t think we’re in a bear market, is really what I’m saying,” he added.

As far as market labels like these go, I’m agnostic. Are we in a bull market, a bear market, a correction or a panic attack? I can’t say.

I know only that the geopolitics of the Ukraine crisis make me nervous in a way no simple market decline can.

It doesn’t pay to panic. But this week, I’m worried.