Their sacrifices were heroic, charging into gunfire on Civil War battlefields. Free Black men from the North took up arms while their family members were still enslaved in the South. They wrote of hope in letters to their wives.

Black troops played a significant role during the Civil War, one that has been preserved in photographs and service records. But historians say their contribution has not been adequately honored. More than 150 years after the end of the Civil War, two Democratic legislators want to fix that.

This month, Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and Representative Eleanor Holmes Norton of the District of Columbia introduced a bill that would award the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’s equivalent of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, to about 200,000 Black troops and naval men who fought for the Union.

The medal’s first recipient was George Washington for his “wise and spirited conduct” in 1776 in the siege and acquisition of Boston. Other recipients rescued survivors of the Titanic, flew polar routes, composed patriotic songs or led troops in World War I.

Black fighters in other wars have received the medal, including the Tuskegee Airmen, the Montford Point Marines and the Harlem Hellfighters, who were the most celebrated regiment of Black soldiers during World War I.

But it has yet to be dedicated to Black forces in the Civil War.

“Despite sacrificing life and limb, hundreds of thousands of African Americans who fought for the Union in the Civil War have largely been left out of the nation’s historical memory,” Ms. Norton said in a statement.

If Congress approves the proposal and President Biden signs it, the medal would represent national appreciation for the fighters’ achievements. Douglas Egerton, a historian at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, N.Y., said it would highlight “exemplary service to the United States.”

“It is a splendid idea because it will remind Americans of this contribution,” he said.

The ‘flag never touched the ground!’

Though some Black regiments had served in combat earlier in the war, the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 gave federal authorization for Black enlistment in the Union Army.

Their regiments were called the United States Colored Troops. It was not an easy introduction. Northern Democrats opposed the idea of Black men under arms, Dr. Egerton said. They encountered racism and were paid less than white soldiers. But as the Union’s need for manpower grew and more Black units were pressed onto front lines, they proved their courage in key battles, Dr. Egerton said.

In the North, the first official Black regiments were organized in Massachusetts in 1863: the 5th Cavalry and the 54th and 55th regiments. In the battle at Fort Wagner in South Carolina in 1863, their courage eroded some of the resistance to Black fighters joining federal ranks. They left families, shed blood and battled sickness.

Some earned medals for bravery.

The 54th regiment initiated the assault on Fort Wagner on July 18. Under Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who was white, the men sprinted up the beach, encountering “ferocious” Confederate fire, and kept running, Dr. Egerton said.

One was William H. Carney. Born into slavery in Norfolk, Va., in 1840, he and his father escaped and moved north to Massachusetts, where he joined the regiment. At Fort Wagner, he seized the flag from a wounded guard and struggled forward to plant it on the parapet.

“He is literally crawling on hands and knees about half a mile,” Dr. Egerton said.

When Union forces retreated, Mr. Carney, who had been pressing his wound with one hand after being shot, carried the flag to his regiment. “Boys, I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground!” he said.

Mr. Carney, promoted to sergeant, was the first Black man to receive the Medal of Honor.

‘Hearts of lions’

About 179,000 Black soldiers served, or about 10 percent of the Union forces, and about 19,000 served in the Navy. They joined as free men in the North, or after fleeing from slavery.

Joseph Glatthaar, a distinguished professor of history at the University of North Carolina, said about 140,000 to 150,000 were formerly enslaved. They had inferior pay and equipment and almost no opportunity for promotion to the high ranks that were held by white officers.

“They are not getting very much training, and when they get thrust into combat, they can’t afford to be perceived as cowards and end up taking risks to prove they are not cowardly,” Dr. Glatthaar said. “They lost huge numbers in the war, and did so in the face of discrimination.”

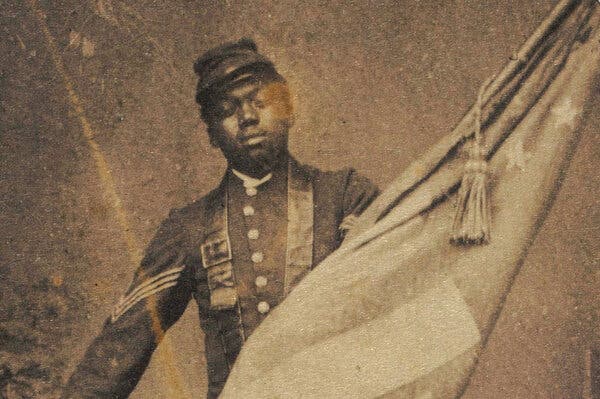

Their voices and images are preserved in photographs, letters, military service records and other documents at the National Archives. Some posed for portraits in their uniforms, seated against painted backdrops.

Enslaved people had little opportunity for formal education, but the writings of Black soldiers reflected their hopes for the Union effort.

Samuel Cabble, who escaped slavery and joined the 55th regiment at 21, wrote from Massachusetts to his enslaved wife, saying that he wanted to have “crushed the system” oppressing her. “Great is the outpouring of the colered peopl that is now rallying with the hearts of lions against that very curse that has seperated you an me,” he wrote.

“Yet we shall meet again,” he wrote, “and oh what a happy time that will be.”

‘We hurry to assist’

Books, movies, memorials and museums have highlighted the role of Black troops in the Civil War. The 1989 movie “Glory” captured the Battle of Fort Wagner.

In the battle of Port Hudson, La., according to a New York Times report from that battlefield in 1863, they “fought with great desperation, and carried all before them. They had to be restrained for fear they would get too far in unsupported. They have shown that they can and will fight well.”

Fourteen were awarded the Medal of Honor for courage in the Battle of New Market Heights in 1864, when two brigades — including members facing the people who had once enslaved them — stormed Confederate fortifications and forced a retreat.

Men who had escaped slavery in the Cape Fear region and joined Union ranks suffered casualties in the Battle of Forks Road, part of the 1865 campaign to take the port of Wilmington, N.C., and sever supplies to Robert E. Lee’s army. In 1865, Black troops were the first Union soldiers to seize Richmond, Va., from the Confederates, leading to the eventual Union victory.

Black women, including Harriet Tubman, worked for Union troops as nurses, spies and scouts. “Black women were always integral to the war effort,” said Holly Pinheiro Jr., an assistant professor of African American History at Furman University.

One of them was Susie King Taylor, who was born into slavery in Georgia. In 1862, Union forces took Fort Pulaski, and her family escaped in the chaos, ending up in Beaufort, S.C., where the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry was formed.

She joined as a “laundress,” she wrote in her memoir, but also maintained guns, learning to “shoot straight and often hit the target,” and served as a nurse.

“It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,” she wrote, “how we are able to see the most sickening sights, such as men with their limbs blown off and mangled by the deadly shells, without a shudder; and instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain, bind up their wounds, and press the cool water to their parched lips, with feelings only of sympathy and pity.”

‘Bullets in his pockets’

Emancipation and citizenship were intertwined with military service, a notion highlighted by Frederick Douglass, who became instrumental in Black recruitment and whose sons, Charles and Lewis, fought with the Massachusetts regiments.

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pockets, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States,” he said.

But even after years of service, Black soldiers struggled with discrimination and unemployment, what Dr. Pinheiro called a “continuance of racism even after giving literally everything.”

Some had no records from enslaved childhoods of exact names, places and dates of birth, illustrating the “whole layer of problems” that persisted throughout their lives. Applications for pensions in particular revealed that struggle, he said.

One was Zachary T. Fletcher, who was born into slavery in McCracken County, Ky., and later served in the army. In 1864, he applied for a pension for his service with the words: “I being raised a slave, I have no record of my age, and if there is any, I do not know anything of it.”

Such records, at least, “are allowing their voices to be heard,” Dr. Pinheiro said. “They are allowing that Black military service happened.”