New York officials found misspending by African American Planning Commission, which runs homeless shelters, but public money continued to flow.

When New York City faced criticism last year for its lax oversight of homeless shelter contracts, officials pledged to root out nepotism and financial misconduct by those who might seek to cash in on the $2 billion system.

Soon after, in February 2021, the officials raised concerns about one nonprofit shelter operator, African American Planning Commission, whose chief executive had secured an unusually high salary — more than $500,000 a year — while the group paid his brother about $245,000 annually and his sister-in-law sat on the board.

Last fall, the officials gave the group a choice: Cut ties with the chief executive’s brother or risk losing tens of millions of dollars in city contracts. The shelter operator agreed to fall in line.

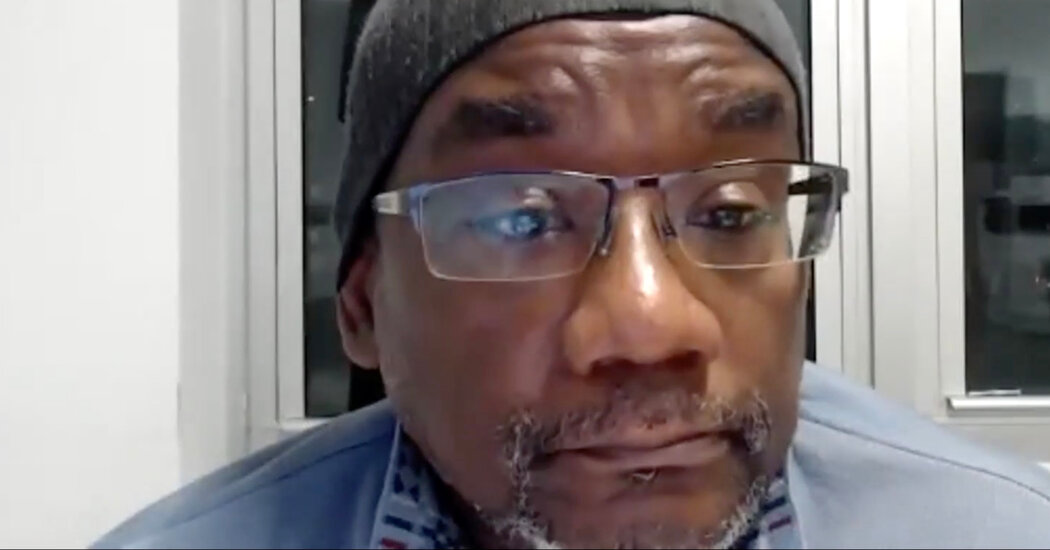

But in fact, the brother remained on the job, and the group remained on the city contractor rolls — collecting $24 million this fiscal year alone, a New York Times examination found. Drawing on records and interviews, the review also showed that the company had made a number of payments to consulting firms tied to the chief executive, Matthew Okebiyi, and his family.

The episode underscores the hands-off approach that New York City has taken to overseeing homeless shelter operators even as it has acknowledged corruption within the system and has promised to crack down.

It also raises questions about what city officials found during a sweeping review — announced after The Times revealed that shelter executives were enriching themselves at taxpayer expense — and whether they are willing to take action against operators who flout rules.

After saying last year that they would conduct an audit of the more than 60 organizations that operate shelters in New York, city officials have declined to answer even basic questions about the inquiry.

They would not say how many providers were cooperating. They would not disclose all of the questions that were being asked. They would not describe what the operators were revealing or say whether any problems had been identified.

Diane Struzzi, a spokeswoman for the city Department of Investigation, which is leading the inquiry, said investigators were “moving forward with the sensitivity and urgency that this review requires.”

“Getting at the facts, documenting them, doing a rigorous, complete review, is not simple or quick,” Ms. Struzzi said.

Officials also have not released certain records related to African American Planning Commission, including the organization’s line-item budgets and lists of the subcontractors and vendors it has paid over the years.

Founded in 1996 by Mr. Okebiyi, the group operates nine shelters in the city, including two for victims of domestic violence, and collected more than $173 million in city money since July 2017.

Mr. Okebiyi said in a statement that his organization had always operated with its clients’ best interests at heart. He said the nonprofit had drawn up detailed plans to comply with city contracting rules and he noted that his brother, Raymond Okebiyi, would stop working as the organization’s finance chief on April 1.

He said that his sister-in-law, Raymond Okebiyi’s wife, would remain on the five-person board as an unpaid, volunteer member and that she had recused herself over the years from decisions involving him and his brother.

Mr. Okebiyi added that he had worked hard to expand his organization and that the number and size of the contracts it had gotten were evidence of its success.

“Over the years, the city has seen what great work we do and has partnered with us to take on more services to fill the unmet need,” he said. “The city is working with us to support us and ensure we can continue to do this high-quality work at this expanded scale.”

African American Planning Commission is just one of about five dozen groups that city officials rely on — compelled by a court order to house every homeless person — to operate shelters in the five boroughs. Last year, the city paid the groups more than $2.6 billion.

City officials have placed nine of those providers on an internal watch list, citing possible conflicts of interest, questionable spending and financial problems. They said they plan to add Mr. Okebiyi’s group to the list but had not finalized the paperwork. All of the organizations have continued to receive city funding.

One reason, city officials said, is that homelessness reached record levels in New York in recent years, and there are a limited number of organizations willing to operate shelters. Against that backdrop, the city has preferred to bring errant organizations into compliance rather than banning them from receiving future contracts, said Isaac McGinn, a spokesman for the Department of Social Services, which oversees shelter contracts.

“The services and programs that thousands of New Yorkers rely on every day are not suddenly canceled or terminated based on one strike and a rush to judgment,” Mr. McGinn said. “The fact is, we provide vital emergency services to thousands of New Yorkers every day — and at the same time, we are reforming and transforming the system.”

Family business

For years, Mr. Okebiyi’s group has been a steady source of employment for members of his family, often operating in ways that could run afoul of city rules.

Initially started by Mr. Okebiyi to operate a Brooklyn domestic violence shelter, African American Planning Commission hired Raymond Okebiyi as an accountant in 2003. By 2020, records show, he had become chief financial officer — reporting to his brother and earning more than $247,000 a year.

At one point, the group also hired an outside firm owned by Raymond Okebiyi, Okayson Consultants, for technology services, according to corporate filings and city records. Mr. Okebiyi said the nonprofit used his brother’s firm off-and-on from 2007 to 2020, but he declined to say how much the consulting firm had been paid.

The group also brought on Raymond Okebiyi’s wife, Onyekwere Onwumere, as a board member and in 2020, hired Mr. Okebiyi’s nephew as a worker at one of its shelters. Mr. Okebiyi said that his nephew no longer worked for the group, and that he had had no role in hiring him.

Mr. Okebiyi’s relatives benefited in other ways. From 2012 to 2016, the group paid an athletic shoe company run by another of Mr. Okebiyi’s brothers, Michael, to provide “tech support,” records and interviews show. Mr. Okebiyi said the payments to the company totaled “less than $20,000 a year.”

African American Planning Commission even hired a firm founded by Mr. Okebiyi himself, Lafayette Consultants, also for “tech consulting,” and made payments to the business until 2019, according to city records.

It was unclear whether Mr. Okebiyi disclosed his ownership of the company before the nonprofit chose it as a contractor, as city rules require. Mr. Okebiyi told The Times that payments to the company were rolled into the compensation he received as the group’s chief executive.

In 2017, as the number of homeless people in the city was swelling, the group sought to expand from domestic violence services to running other types of shelters.

It won lucrative new contracts and grew rapidly, with Mr. Okebiyi’s salary rising apace. He was earning more than $532,000 a year by 2019, tax filings show — one of the highest salaries paid to any nonprofit shelter executive in New York that year.

Mr. Okebiyi said the group’s board had approve the increases to his compensation, and that the raises were tied to his performance and expanded job responsibilities.

By May 2019, the city was paying the group tens of millions of dollars a year, and the relationships between Mr. Okebiyi, his brother and sister-in-law caught the attention of city investigators.

Records show that the Department of Investigation examined questions of nepotism at the organization and concluded that it was inappropriate for Mr. Okebiyi to supervise his brother and to have a relative on the board overseeing him. But the agency closed the matter without taking action, aside from recommending that the city devise a better way for executives to disclose conflicts of interest.

In February 2021 — more than a year after first flagging problems at the group — the city sent a letter to African American Planning Commission demanding answers about Mr. Okebiyi’s high salary, his brother’s employment and payments made to his family’s businesses, records show. City officials ordered the group to restructure but the nonprofit refused, Mr. McGinn, the social services spokesman, said.

Last fall, the Department of Social Services issued its stern directive to Mr. Okebiyi, who agreed to stop employing his brother.

Lax oversight

But Raymond Okebiyi has remained on the nonprofit’s payroll, records and interviews show.

In response to questions from The Times, the city echoed what Mr. Okebiyi had said: that Raymond Okebiyi would part ways with the organization on April 1.

Despite the lack of immediate compliance, Mr. McGinn, the social services spokesman, said the city had been effective at monitoring African American Planning Commission and other shelter operators.

But New York’s record of policing its homelessness contractors has been far from perfect.

Last year, The Times revealed that one shelter executive, Victor Rivera, had hired family members, steered contracts to close associates and intermingled nonprofit business with for-profit companies he ran. He pleaded guilty this month to federal charges of accepting bribes and kickbacks from contractors doing work with his organization.

Another report by The Times, in October, disclosed that the chief executive of CORE Services Group, who was making $1 million a year, steered $32 million to for-profit companies tied to him. A month later, the city announced it would sever contracts with CORE. The group will nonetheless receive city funds through March.

A third article found that properties owned by a landlord whom the city had castigated over shoddy housing conditions had been chosen as sites for nearly a third of New York’s new shelters — even as the landlord required some nonprofits that rented his buildings to use his maintenance company. The landlord has continued to do business with the city.

Social services officials have said the broad audit they began last year was meant to root out bad actors, focusing on conflicts of interest, nepotism and questionable contracts.

So far, a number of operators have responded to inquiries by investigators, who have reviewed about 3,000 records, said Ms. Struzzi, the Department of Investigation spokeswoman.

She declined to say when the review would be complete.

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.