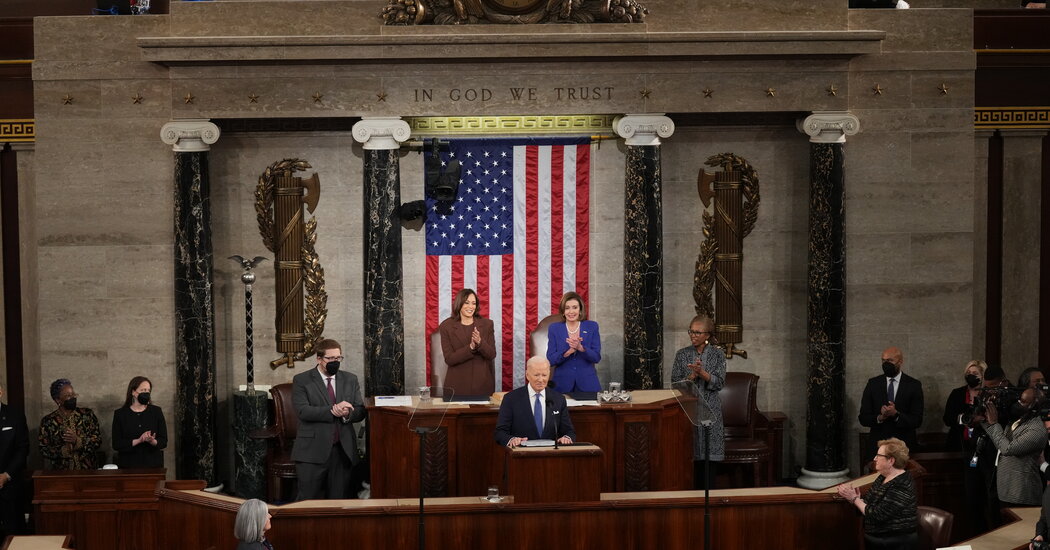

President Biden’s State of the Union address on Tuesday night sounded like two speeches grafted together.

First came a stirring paean to the bravery of the Ukrainian resistance and a vow to ravage Russia’s economy in a bid to turn back Vladimir Putin’s tanks. Biden forswore sending troops to fight alongside Ukrainians, but he promised to wage financial war on their behalf, cutting Russia off from its foreign reserves, its oligarchs off from their yachts and villas, and its economy off from the financial flows and technological trades needed for continued growth.

“Throughout our history, we’ve learned this lesson,” Biden said. “When dictators do not pay a price for their aggression, they cause more chaos.”

Then came the more traditional speech, the one Biden would have given if the State of the Union had come a month ago. He bragged about the economic growth, job creation, infrastructure investment and wage gains seen on his watch. He admitted that inflation was undermining America’s economic boom, but that he had a plan.

“One way to fight inflation is to drive down wages and make Americans poorer,” Biden said. “I have a better plan to fight inflation. Lower your costs, not your wages. Make more cars and semiconductors in America. More infrastructure and innovation in America. More goods moving faster and cheaper in America. More jobs where you can earn a good living in America. And instead of relying on foreign supply chains, let’s make it in America.”

That these speeches felt so tonally separate was a rhetorical choice, not a reflection of reality. Because they are circling the same problems — and the same solutions.

Let’s start with the problems. The West’s sanctions on Russia are punishing precisely because Russia is intertwined with Western economies. That’s particularly true in energy and agriculture, where Russia is a major exporter. The sanctions, as proposed, are ferocious in cutting Russia off from global financial markets, but they exempt energy and agricultural goods. That’s a big loophole. “If we’re not interrupting the payment for energy deliveries, we are not hitting the bit of the Russian economy which generates the juice, which sustains Putin’s regime,” Adam Tooze, director of the European Institute at Columbia University, told me.

Those exemptions exist because the United States and Europe fear the pain that cutting off Russia’s core exports would cause their economies. That’s exactly what Putin is banking on, and what mutes the West’s leverage over him. But the images of Russia’s invasion, and the heroism of the Ukrainian people, is hardening the West’s resolve and quickly.

The sanctions imposed on Friday were a pale shadow of what the West did on Monday, when it took aim at Russia’s central bank and its fortress of foreign currency reserves. Putin’s hope for a lightning invasion, with only token resistance, has crumbled, and Russia appears to be preparing for a far more brutal campaign. Pressure will build on Biden and the Europeans to choke off Russia’s energy exports. Both the sanctions we’ve seen and the sanctions that may come will be felt, in America and Europe and elsewhere, as inflation.

Biden signaled all this, if a little obliquely. “To all Americans, I will be honest with you, as I’ve always promised,” he said. “A Russian dictator, invading a foreign country, has costs around the world. I’m taking robust action to make sure the pain of our sanctions is targeted at Russia’s economy. And I will use every tool at our disposal to protect American businesses and consumers.” Every tool will not be enough if Biden is as committed to stopping Putin as he says.

I don’t want to suggest there’s symmetry here. The pain the United States and Europe can inflict on the Russian economy dwarfs any feedback effects. Measured in G.D.P., Russia has a smaller economy than Italy, and it is one-fourteenth the size of that of the United States. But the exemptions tell the story. For all Biden’s resolve on Tuesday night, he did not try to prepare Americans to sacrifice on behalf of Ukrainians in the coming months, if only by paying higher prices at the pump. Instead, he said, “my top priority is getting prices under control.” That’s the tension Putin is exploiting.

At the same time, it adds force to the agenda Biden laid out in the rest of his speech. “Economists call it ‘increasing the productive capacity of our economy,’” Biden said. “I call it building a better America.”

There are parts of Biden’s agenda that, if passed, could help to lower prices for families, rapidly. Medicare could negotiate drug prices next year. Child care subsidies could take effect quickly. There is no resource limitation stopping us from lowering Obamacare premiums. The same cannot be said for Biden’s more ambitious proposals to build the productive might and critical supply chains of the United States. To decarbonize the economy and rebuild American manufacturing and lead again in semiconductor production is the work of years, perhaps decades. It won’t change prices much in 2022 and 2023.

But it needs to be done, and not just because of Russia. Covid was another lesson, as America was caught without crucial supply chains for masks and protective equipment in the beginning of the pandemic, and without enough computer chips as the virus raged on. And while I don’t like idly speculating about conflict with China, part of avoiding such a conflict is making sure its costs are clear and our deterrence is credible. As of now, whether we have the will to defend Taiwan militarily is almost secondary to whether we have the capability to sever ourselves from Chinese supply chains in the event of a violent dispute.

Biden devoted a large chunk of his speech to his Buy American proposals, which economists largely hate, but which voters largely love. As a matter of trade theory, I’m sympathetic to the economists, but as Russia is proving, there’s more to life than trade. You could see that in an analysis done by The Economist, which has long been one of the loudest voices arguing for the logic of globalization. “The invasion of Ukraine might not cause a global economic crisis today but it will change how the world economy operates for decades to come,” it wrote. Russia will become more reliant on China. China will try to become more economically self-sufficient. The West is going to think harder about depending on autocracies for crucial goods and resources.

This was, in the end, the unfulfilled promise of Biden’s speech. Russia’s invasion and America’s economy were merely neighbors in the address, but no such borders exist. And connecting them, explicitly, would bring more coherence and force to Biden’s agenda.

Energy, for instance, is central to Russia’s wealth, power and financial reserves. Biden could have used that to mount a full argument for his climate and energy package, which is languishing in the wreckage of Build Back Better. As the energy analyst Ramez Naam has noted, Biden’s package would reduce American demand for oil and natural gas, both of which would weaken Russia — and plenty of other petrostates we’d prefer that neither we nor our allies were dependent on.

Helpfully for Biden, Joe Manchin seems not just open to this line of argument — he’s leading on it. “The brutal war that Vladimir Putin has inflicted on the sovereign democratic nation of Ukraine demands a fundamental rethinking of American national security and our national and international energy policy,” the senator said in a statement on Tuesday.:

The United States, our European allies and the rest of the world cannot be held hostage by the acts of one man. It is simply inexplicable that we and other Western nations continue to spend billions of dollars on energy from Russia. This funding directly supports Putin’s ability to stay in power and execute a war on the people of Ukraine.

Manchin went on to say that “we must commit to once again achieving complete energy independence by embracing an all-of-the-above energy policy to ensure that the American people have reliable, dependable and affordable power without disregarding our climate responsibilities.” I do not claim to know what Manchin truly has in mind here, nor what he will vote for when the roll is called. But it is a door ajar, and Biden should step through it.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.