“We should all agree,” President Biden declared in his State of the Union address on Tuesday:

The answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them. Fund them with resources and training. Resources and training they need to protect their communities.

It’s not hard to understand why this paragraph was in the speech. For more than a year, moderate and conservative Democrats have been in a state of panic over the impact of “defund the police” — a controversial slogan from the George Floyd protests of 2020 — on their electoral fortunes.

Despite slim evidence of any particular impact on voters, and despite even slimmer evidence that “defunding the police” is a priority for much more than a small handful of elected Democrats, anger and consternation over the slogan continues to shape political and strategic thinking within the Democratic Party.

What doesn’t, somehow, shape political and strategic thinking about law enforcement within the Democratic Party is the reality of police budgets in this country. The president’s rhetoric notwithstanding, police departments in the United States are not actually strapped for funds.

Let’s just look at the numbers. Despite some cuts, according to a 2021 analysis of police budgets in the nation’s 50 largest cities by Bloomberg CityLab, law enforcement spending as a share of general expenditures rose slightly from 13.6 percent to 13.7 percent from 2020 to 2021, even as many cities cut spending in other areas as a result of the pandemic. And out of 42 major cities where Democrats gained votes from 2016 to 2020, more than half increased police spending for fiscal year 2021. Some cities that cut spending, or pledged to cut it, later reversed or restored that funding.

In 2020, for example, New York City’s former mayor, Bill de Blasio, pledged to cut $1 billion from the New York Police Department’s $6 billion budget. In the end, most of these cuts never materialized. Instead, de Blasio approved, for fiscal year 2022, a $200 million increase in police spending.

City officials in Austin, Texas, embarked on a similar journey, cutting the city’s police budget during the George Floyd protests, reversing those cuts the following year and then expanding the budget for law enforcement with additional funds for more officers and more training. For this year, the Austin Police Department budget stands at $442 million, a record high.

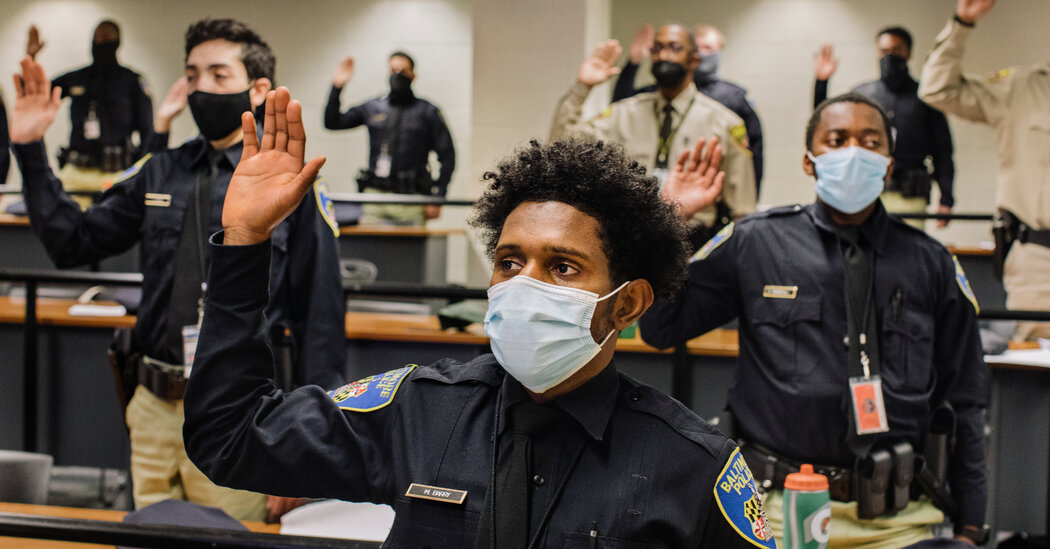

Last year, the mayor of Los Angeles, Eric Garcetti, proposed an $11.2 billion city budget that increased funding for the L.A.P.D. from $1.71 billion for fiscal year 2021 to $1.76 billion for fiscal year 2022. In Baltimore, likewise, police funding grew to $555 million for 2022, a $28 million increase from the previous fiscal year.

Yes, since the start of the pandemic there has been an increase in violent crime. It has been happening everywhere, in big cities and small towns, in Democratic strongholds and Republican ones. At the same time, there is no real relationship between crime rates and police budgets. As Philip Bump observed for The Washington Post in 2020, “More spending in a year hasn’t significantly correlated to less crime or to more crime. For violent crime, in fact, the correlation between changes in crime rates and spending per person in 2018 dollars is almost zero.”

And even if there were a connection, it is not as if there has been a peace dividend for crime. Cities spend big on police when crime is up and they spend big on police when crime is down. They spend big when police solve crimes and they spend big when they don’t. In 2020, the Miami-Dade County police department — one of the largest in the country — resolved (or cleared) just over 40 percent of the violent crimes reported in its jurisdiction. Commit a violent crime in Miami-Dade and you had a roughly 6-in-10 chance of not being caught, at least not that year. Despite that low clearance rate — despite a decade of low clearance rates — the budget for the Miami-Dade County police department has only increased, reaching nearly $800 million for this fiscal year, up from $765 million for 2021 and $707 million for 2020.

In short, there is no pressing, national need for greater police funding. If anything, police departments and their allies have skillfully used anxiety over “defund” to successfully lobby for even larger budgets, despite the striking inability of many police departments to solve crimes and clear murders.

There does remain, however, a pressing, national need for police accountability. In theory, the police are subordinate to elected officials. In practice, police departments in many areas exist beyond democratic control. That’s especially true in states where police contracts and state law make it difficult, if not impossible, to remove bad or abusive officers from their jobs.

In Oakland, Calif., for example, police simply ignored a 2018 ordinance that placed limits on police use of surveillance technology. In Asheville, N.C., the prospect of accountability for bad actors in the police department led to an exodus of officers from the force. When, in 2014, de Blasio expressed sympathy for the death of Eric Garner at the hands of the N.Y.P.D., the city’s police officers went on the offensive against him, as if this were an unacceptable breach of conduct.

In other words, President Biden’s pledge to “fund the police” is divorced from the actual circumstances of police funding in the United States. It is a solution to a problem that does not exist. Worse, if Congress acts on this pledge and provides more money for cops, it will be funneling money to police departments that hold the people they serve, and the elected leaders they presumably serve under, in contempt.

The most memorable images from the protests of 2020 were those of civil unrest, but we should not forget the extent to which those protests were marked by police unrest as well. Police drove vehicles into crowds, assaulted peaceful bystanders, pepper-sprayed cooperative protesters and attacked journalists with so-called nonlethal rounds.

In one particularly egregious example of misconduct, police in Portsmouth, Va., charged a state senator and several public defenders with felonies over the protests in that city and then served a summons on the vice mayor, who had called for the police chief’s resignation.

Few police officers are held accountable for killings. Even fewer have to answer for more common forms of abuse and bad behavior. And too many cops act with impunity, as if they are above the laws that govern the rest of us. We don’t need to “fund the police” — American law enforcement has more than its fair share of cash — we need to control them.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.