He successfully represented the Black Panthers, environmentalists who accused the government of conspiracy and Attica prison inmates.

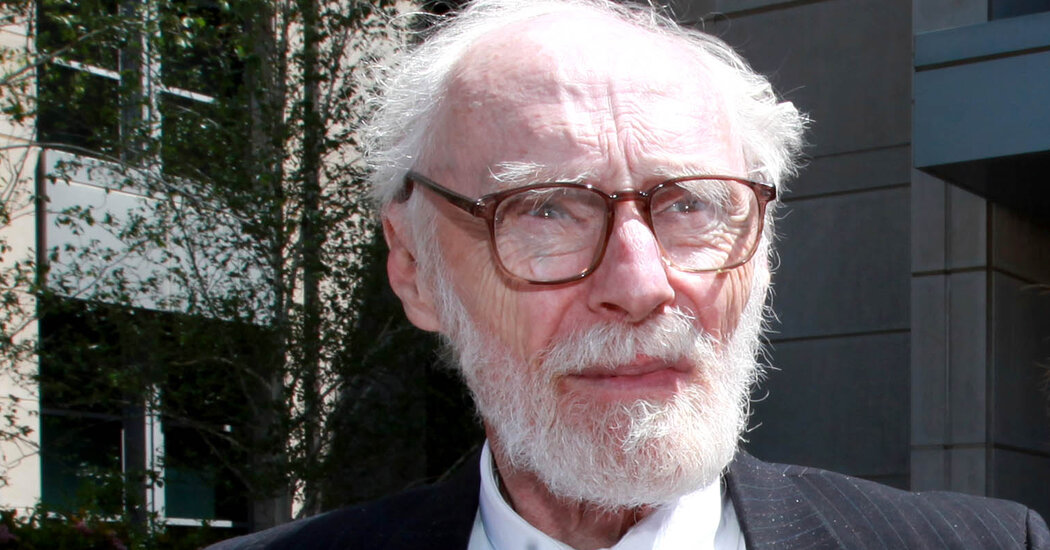

Dennis Cunningham, a civil rights lawyer who successfully sued the government on behalf of the Black Panthers, rebellious Attica prison inmates and fervid environmentalists who claimed they were victims of official misconduct, died on Saturday at his son’s home in Los Angeles. He was 86.

The cause was cancer, his daughter Bernadine Mellis said.

Mr. Cunningham was not as well known as some of his colleagues, but he represented a wide range of protesters after being inspired by the 1963 civil rights March on Washington — “the engine of my enlightenment,” he called it — and attending law school at night in the 1960s.

He practiced in Chicago, where he was a founder of the storefront People’s Law Office; in upstate New York, where a civil suit stemming from the 1971 prison riot at the Attica Correctional Facility was finally settled in 2001; and in San Francisco, where he moved in the early 1980s to be closer to his children.

Mr. Cunningham joined the team of lawyers who sued the authorities after a police raid on a Chicago apartment in which Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, leaders of the Black Panther Party in Illinois, were shot to death in 1969.

Within hours of the police shooting, Mr. Cunningham called Gerald L. Shargel, a fellow fledgling civil liberties lawyer in New York, for advice. Mr. Shargel recommended that Mr. Cunningham immediately enlist a forensic expert to inspect the apartment, the first step in establishing a chain of evidence that helped prove their allegation that the raid was the result of a government conspiracy to murder Mr. Hampton.

After an 18-month trial, the suit was finally settled for $1.85 million on behalf of the survivors and the families of the two victims in 1982.

“It was all about Dennis’s commitment, which is what you want in a lawyer who’s trying to do the right thing,” Mr. Shargel said in a phone interview. “Dennis led that fight for years.”

Mr. Cunningham, Michael Deutsch, Elizabeth Fink and Joseph Heath represented 62 inmates indicted in the aftermath of the Attica riot; eight were convicted. In 1974, the lawyers filed a civil suit on behalf of the Attica Brothers Legal Defense Fund, which was settled for $12 million, including legal fees, a quarter century later.

In 2002, Mr. Cunningham helped persuade a jury in California to award $4.4 million to two Earth First environmentalists who contended that their rights had been violated by the local and federal officers who arrested them.

The authorities said the environmentalists, Darryl Cherney and Judi Bari, were on their way to promote demonstrations against the logging of ancient redwood trees in 1990 when a pipe bomb in their car exploded. Ms. Bari’s pelvis was crushed by the blast and Mr. Cherney was slightly wounded.

The authorities said the bomb had accidentally detonated while the pair were transporting it to use for eco-terrorism. Supporters of Mr. Cherney and Ms. Bari said the timber industry or the government had planted the bomb. Criminal charges were eventually dropped for lack of evidence.

After 17 days of deliberations, a federal jury in a civil trial affirmed the plaintiffs’ contention that the F.B.I. and the Oakland police had violated their civil rights and First Amendment rights by defaming the pair.

The car bomb case became the subject of a documentary film, “The Forest for the Trees” (2005), directed by Mr. Cunningham’s daughter Bernadine Mellis.

Mr. Cunningham acknowledged that “as lawyers, we have it drilled into us that we owe a duty of representation to each client, the rest of the world be damned.” But he was quoted in the book “Representing Radicals” (2021) as saying that many of the cases he took on behalf of politically-motivated defendants had to be approached differently.

In such cases, he said, his obligation is to “take care not to undermine the values or the goals of the client’s activism.”

Dennis Dickson Cunningham was born on Jan. 2, 1936, in Glencoe, Ill., to Robert M. Cunningham Jr., an author, editor and health care policy consultant, and Deborah (Libby) Cunningham, a homemaker.

When he was 15, he entered the University of Chicago under a Ford Foundation program for students who had completed two years of high school.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1955, he performed in theater companies, including The Second City, where he met and married Mona Mellis. Their marriage ended in divorce.

Besides his daughter Bernadine, he is survived by his son, Joseph Mellis; his daughters, Delia Mellis and Miranda Mellis; three grandchildren; his brother, Rob; and his partner, Mary Ann Wolcott.

Mr. Cunningham was in his late 20s when, inspired by the civil rights movement, he earned a law degree at night from Loyola University in Chicago in 1967.

He was admitted to the bar just in time to defend demonstrators arrested at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. With the help of colleagues from the National Lawyers Guild, he helped found the People’s Law Office in a converted sausage store to assist protesters facing charges for what they viewed as their efforts to bring about social and political change.

“We had boldly decided to call ourselves the People’s Law Office — informally at least — and our purpose was easily encapsulated in the obligation to be worthy of that name,” Mr. Cunningham recalled.

He later represented groups opposed to apartheid and to dictatorships in Central America, and others that favored more support for the homeless and the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or Act Up.

After settling in San Francisco, he worked with another lawyer, Ben Rosenfeld, on the Bari case and other litigation.