President Putin has put Russia’s nuclear forces on “special” alert, raising concerns around the world.

But analysts suggest his actions should probably be interpreted as a warning to other countries not to escalate their involvement in Ukraine, rather than signalling any desire to use nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons have existed for almost 80 years and many countries see them as a deterrent that continues to guarantee their national security.

How many nuclear weapons does Russia have?

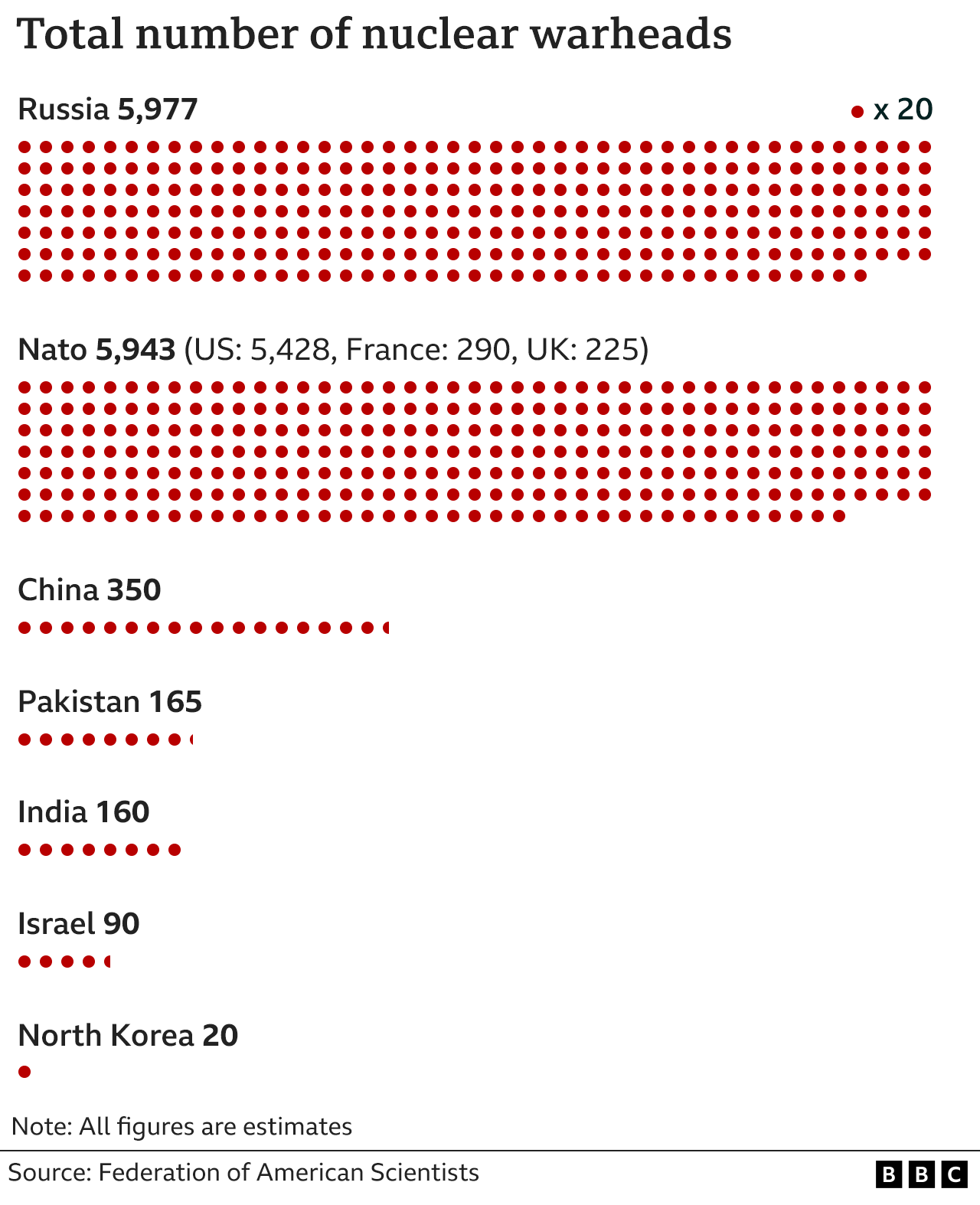

All figures for nuclear weapons are estimates but, according to the Federation of American Scientists, Russia has 5,977 nuclear warheads – the devices that trigger a nuclear explosion – though this includes about 1,500 that are retired and set to to be dismantled.

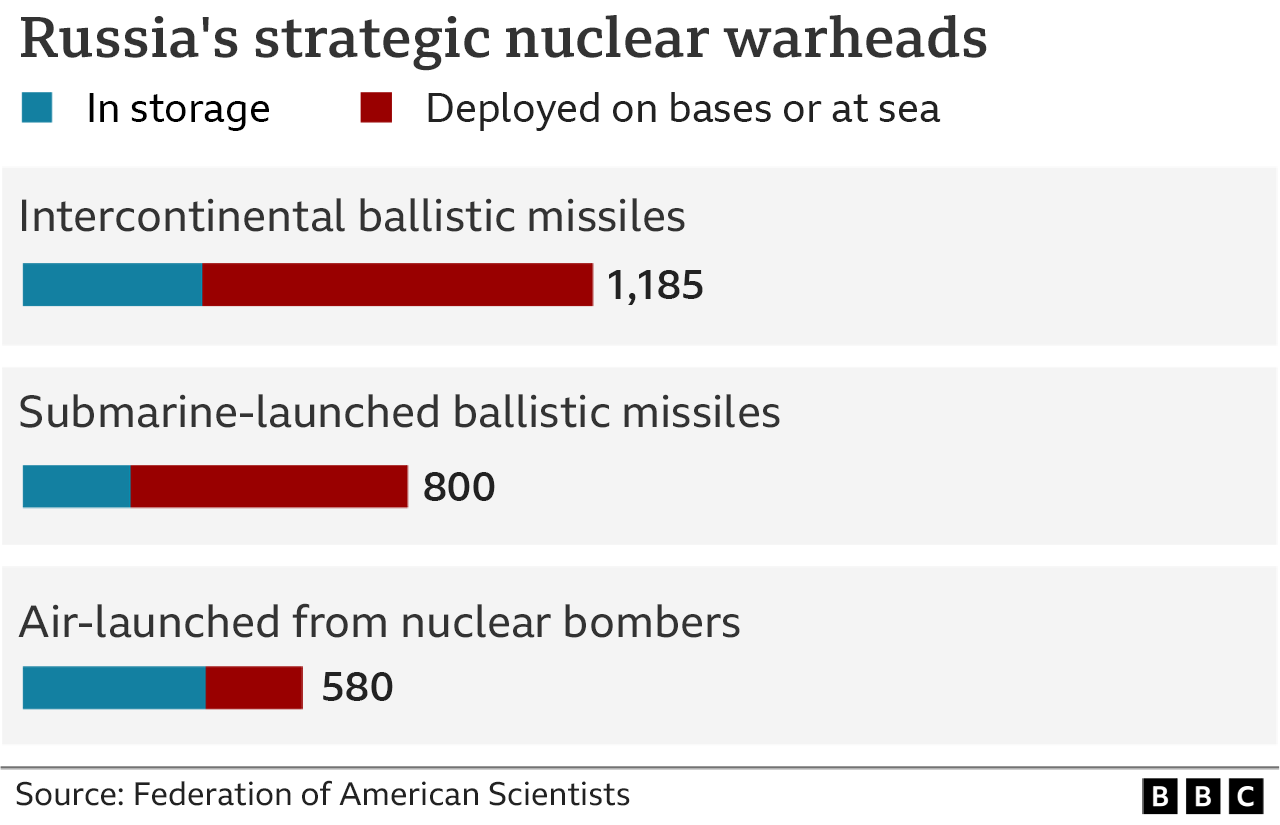

Of the remaining 4,500 or so, most are considered strategic nuclear weapons – the ones usually associated with nuclear war, which can be targeted over long distances.

The rest are smaller, less destructive nuclear weapons for short-range use on battlefields or at sea.

But this does not mean Russia has thousands of long-range nuclear weapons ready to go.

Only 1,588 Russian warheads are currently “deployed”, experts say, meaning sited at missile and bomber bases or on submarines at sea.

How does this compare with other countries?

Nine countries have nuclear weapons: China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the US and the UK.

China, France, Russia, the US and the UK are also among 191 states signed up to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

Under the agreement, they have to reduce their stockpile of nuclear warheads and, in theory, are committed to their complete elimination.

And it has reduced the number of warheads stored in those countries since the 1970 and 80s.

India, Israel and Pakistan never joined the NPT – and North Korea left in 2003.

Israel is the only country of the nine never to have formally acknowledged its nuclear programme – but it is widely accepted to have nuclear warheads.

Ukraine has no nuclear weapons and, despite accusations by President Putin, there is no evidence it has attempted to acquire them.

- LIVE: Latest updates from on the ground

- THE BASICS: Why is Putin invading Ukraine?

- MAPS: Tracking day six of Russia’s invasion

- RUSSIA SANCTIONS: ‘If I could leave, I would’

- UKRAINE: Desperate scenes in Lviv train station

- IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict

How destructive are nuclear weapons?

Nuclear weapons are designed to cause maximum devastation.

The extent of the destruction depends on a range of factors, including:

- the size of the warhead

- how high above the ground it detonates

- the local environment

But even the smallest warhead could cause huge loss of life and lasting consequences.

The bomb that killed up to 146,000 people in Hiroshima, Japan, during World War Two, was 15 kilotons.

And nuclear warheads today can be more than 1,000 kilotons.

Little is expected to survive in the immediate impact zone of a nuclear explosion.

After a blinding flash, there is a huge fireball and blast wave that can destroy buildings and structures for several kilometres.

What does ‘nuclear deterrent’ mean and has it worked?

The argument for maintaining large numbers of nuclear weapons has been having the capacity to completely destroy your enemy would prevent them from attacking you.

The most famous term for this became mutually assured destruction (Mad).

Though there have been many nuclear tests and a constant increase in their technical complexity and destructive power, nuclear weapons have not been used in an armed confrontation since 1945.

Russian policy also acknowledges nuclear weapons solely as a deterrent and lists four cases for their use:

- the launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territory of the Russian Federation or its allies

- the use of nuclear weapons or other types of weapons of mass destruction against the Russian Federation or its allies

- an attack on critical governmental or military sites of the Russian Federation that threatens its nuclear capability

- aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy

How worried should we be? The likelihood of nuclear conflict may have gone up slightly but remains low.

Even if Putin’s threat is meant as a warning rather than signalling any current desire to use the weapons, there is always the risk of miscalculation if one side misinterprets the other or events get out of hand.

UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace told BBC News the UK had so far seen no change in the actual posture of Russia’s nuclear weapons.

That will be watched closely, intelligence sources confirm.

You can read more from Gordon Corera here.

-

Day 6: Tracking Russia’s invasion in maps

-

Why has Putin invaded Ukraine?

-

Could the fighting spread across Europe? And other questions