Americans are used to wars against people who don’t so casually speak our language. Zelensky can respond to Russian propaganda by directly addressing the Russian people — in Russian.

The thing about the videos from the war in Ukraine in 2014 was that there were very few war videos. It was, at least at first, a small-arms war. Fighting, when it erupted, happened on city streets. As soon as shots were fired, whoever was making the video would put away the phone and run.

The videos that characterized the conflict were not of rifle fire but of protests: riot police beating demonstrators as people shouted, “What are you doing?”; later, young men on the same square, outfitted in motley assortments of helmets and kneepads, counterattacking; videos of people arguing; videos of people being forced, in eastern Ukraine, to get on their knees. After pro-Russian forces took over cities in the east and the Ukrainian Army finally moved to restore its authority, there were videos of pro-Russian protesters trying to prevent tanks from entering their towns. These were the images of a country falling apart.

Soldiers speak Russian as they fire on Russian tanks. Locals speak Russian as they survey annihilated Russian columns.

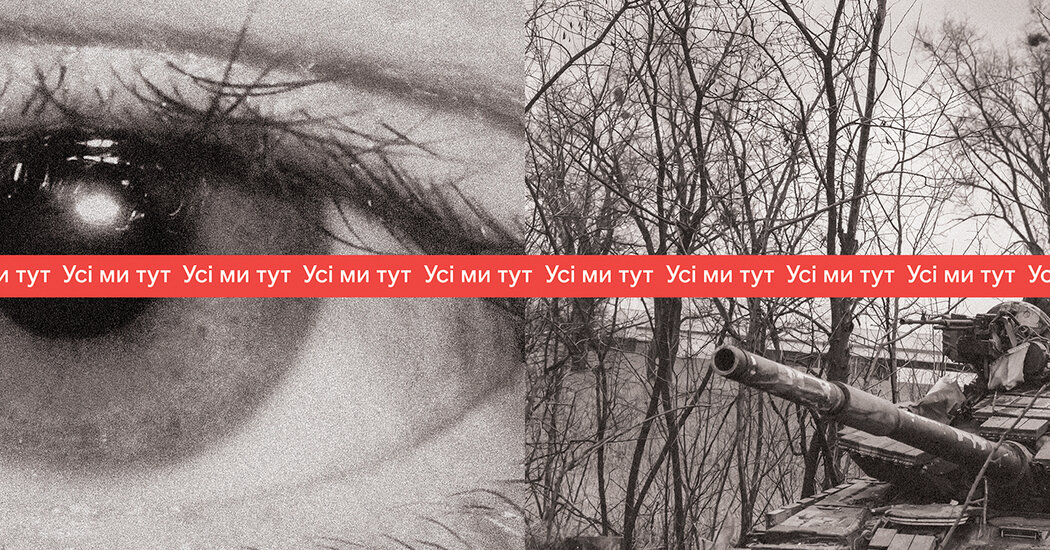

Now war has arrived again to Ukraine — in the east of the country, it never left — and with it come new videos. In the first hours of the war there were rumors that President Volodymyr Zelensky had fled from Kyiv, as Viktor Yanukovych fled before him in 2014. Then came Zelensky’s video response. Standing in the square in front of the president’s office on Bankova Street in central Kyiv, surrounded by his political allies and advisers, he pointed to each in turn and said that they were tut — here. The head of the party faction was tut. The chief of staff was tut. The prime minister was tut. His adviser Podoliak was tut. “Vsi my tut,” he concluded. “We’re all here.”

The next day brought a video from the front, a dashcam clip of a man pulling up to an armored vehicle by the side of the road. “What happened, boys?” he says to the soldiers milling around behind the vehicle.

“We ran out of gas,” one of them says.

“Want me to tow you? Back to Russia?” the driver asks.

The soldiers laugh. The driver asks if they know where the road they’re on leads to. They say they don’t. He says it goes to Kyiv. They seem surprised.

This video was revealing on a number of levels. There was the courage of the driver, pulling up to armed soldiers in a war zone, and the simple incompetence of the Russian invasion, allowing an armored vehicle to run out of gas on the way to Kyiv. But most fascinating was the fact that the driver could communicate so easily, so freely, with the Russian soldiers. Like a great many of his countrymen — especially in the east, where the invasion began — he is a native Russian speaker.

The language question has been a painful one in Ukrainian politics, though it looms far larger in the minds of Kremlin propagandists than it does in actual Ukrainian life. There are young Ukrainians for whom it is a matter of principle and honor to not speak Russian, the language of the former empire. And the government periodically passes contentious laws that aim to encourage further Ukrainianization. But most people continue to speak the language that makes most sense to them in their everyday lives, sometimes switching between the two depending on the context and situation. Russian propaganda claims that the language is discriminated against, and there are people in Russia who believe that you will get shouted at, or even attacked, for speaking Russian in Kyiv. Yet in the videos now emerging from Ukraine, over and over again, people are speaking Russian. Soldiers speak Russian as they fire rocket-propelled grenades at Russian tanks. Locals speak Russian as they survey annihilated Russian columns. Americans are accustomed to wars that take place far away, against people who don’t so casually speak our language, but of course most wars take place between people who live right next to one another. Russia invading Ukraine is less like our wars in Iraq or Vietnam and more like the United States invading Canada.

What was Putin thinking? We know a fair amount about this: Last summer he published, on the Kremlin’s website, a very long essay on “The Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine.” He repeated some of its contents in a long televised speech on the eve of his invasion. The essential argument was that Ukraine could not exist if it moved away from Russia — because it was part of Russia, and always had been.

The answer to these historical ruminations came, again, from Zelensky — and, again, in Russian, as the president switched languages during a speech in order to directly address the Russian people. Responding to the Kremlin’s claims that it was protecting the separatist regions from Ukrainian plans to take them by force, Zelensky asked whom, exactly, Russia thought he was going to bomb. “Donetsk?” he asked incredulously. “Where I’ve been dozens of times, seen people’s faces, looked into their eyes? Artyoma Street, where I hung out with my friends? Donbas Arena, where I cheered on our boys at the Eurocup? Scherbakov Park, where we all went drinking after our boys lost? Luhansk? The house where the mother of my best friend lives? Where my best friend’s father is buried?”

Russia-Ukraine War: Key Things to Know

Expanding the war. Russia launched a barrage of airstrikes at a Ukrainian military base near the Polish border, killing at least 35 people. Western officials said the attack at NATO’s doorstep was not merely a geographic expansion of the invasion but a shift in Russian tactics.

Zelensky was making an argument about nationhood — that it is formed not by history or by language, but by individual memories, by personal connections. “Note,” he continued, “that I’m speaking now in Russian, but no one in Russia understands what I’m talking about. These place names, these streets, these families, these events — this is all foreign to you. It’s unfamiliar. This is our land. This is our history. What are you going to fight for? And against whom?”

He was also making an argument about history. History was not something that happened centuries ago, as in Vladimir Putin’s boring essay, but something that happened in the course of a single lifetime. Your home was the place that stored your memories and the memories of your loved ones. And when someone tried to invade it, there was only one response.

As the fighting continued, and as the Russian Army responded to Ukrainian resistance by dropping huge bombs on Ukrainian cities, the news and the images out of Ukraine became bleaker. And there is no question that the worst and most terrifying parts of war take place out of sight, with no smartphones filming. But in that first week, we learned important things. Few expected this level of resistance from Ukraine. The country had changed since 2014; it had taken time to think about what happened in Donbas and Luhansk, and to see what became of those places. And in Zelensky it had found a surprising leader — a Russian-speaking Jew who was nonetheless a profound patriot of Ukraine. What he has offered is a vision of a transnational, multiethnic, multilingual country on the eastern edge of Europe, and something worth fighting for.

Keith Gessen teaches journalism at Columbia and is the author of the novel “A Terrible Country.”

Source photographs: Alexander Venzhega/EyeEm/Getty Images; Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times, via Getty Images