Listen to This Article

Audio Recording by Audm

To hear more audio stories from publications like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.

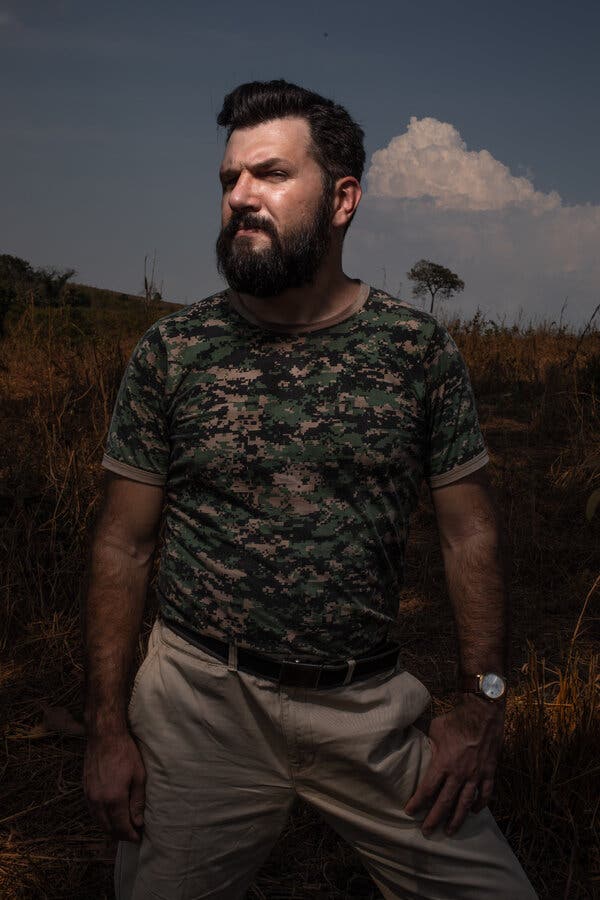

On a sweltering afternoon in the wilds of the Brazilian Amazon, Edward Luz rode on the back of a motorbike into a forest clearing to confront a squad of combat-armed environmental police who, for their own safety, had helicoptered in. Luz is an anthropologist, a tall, powerfully built man of 43. He is a right-wing activist and, figuratively speaking, a hired gun. On that February afternoon in 2020, he wore tinted prescription sunglasses, a bushy beard and a radical haircut close-cropped on the sides. He did not have access to a helicopter. To get to the clearing, he traveled for eight hours by a ferry crossing and down muddy tracks from Altamira, a small city in the state of Pará on the far side of the wide brown Xingu river.

The clearing contained a corral, a shed and a makeshift shack. It was an illegal homestead carved by settlers out of a 550-square-mile Indigenous reserve that is meant to be inviolate. The environmental police intended to expel the settlers by burning their structures, as they had burned more than 200 similar constructs over the previous few weeks. The reserve is called Ituna-Itatá after two small rivers there. It was established in 2011 for the protection of an isolated Indigenous group that has never been contacted by outsiders or fully confirmed to exist. Despite the reserve’s special status, it has become among the most invaded Indigenous territories in all of Brazil since the election of the pro-development, anti-regulatory president, Jair Bolsonaro, in 2018 — a poster board for the Amazon’s eventual demise.

The creation of Indigenous reserves is meant to serve a dual purpose: slowing deforestation through broad restrictions on extractive activities (logging, ranching, farming, mining) while simultaneously protecting Indigenous cultures. The arrangement’s advantages may seem obvious from a distance, but they are ignored by large numbers of Amazonian pioneers whose main concerns do not include cultural diversity or the preservation of nature. These are Bolsonaro’s people. Those who live in the forests endure hardscrabble lives as wildcat miners, loggers and subsistence farmers. Ample documentary evidence exists that many in Ituna-Itatá also work as agents of speculative land-grabbing schemes and related forms of criminal enterprise.

In Ituna-Itatá, Luz was hired by a local association of settlers to challenge the claim that the territory was inhabited by an isolated tribe — and by extension, the legitimacy of the reserve and the legality of the policing taking place there. Luz was raised in the Amazon by evangelical Brazilian missionaries, affiliates of a Florida-based group called the New Tribes Mission, whose beliefs he abandoned as a young man when he set off on a vaguely Marxist college career. That career stopped short of a Ph.D. when Luz decided to throw it all over and set himself up as a consultant for the diametrically opposed camp promoting commercial interests in the region and arguing against the idea of exceptional Indigenous rights. Recently he had acquired a measure of fame by lending his energies to some of the most visible forces shaping the Amazon today — not as we might wish them to be, but as they have evolved. Renowned anthropologists at Brazilian universities and government officials accused him of harboring hidden agendas toward Indigenous peoples, a charge that Luz disputes. Some critics feared him, though more because of the company he keeps than of any evidence that he might resort to violence.

The police he confronted in the clearing were not of the sort to be pushed around. They belonged to a federal agency called IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente), which was formed in 1989 not to protect Indigenous groups but to enforce environmental laws, particularly those meant to counter deforestation in the Amazon. The agency is famously despised by Bolsonaro, who as a junior legislator, after being ticketed for fishing in a marine reserve, proposed a bill prohibiting field agents from carrying weapons — a tantrum, even as a suggestion, that in the context of a hostile environment some agents regarded as posing immediate lethal threats to them. Such is the hostility toward IBAMA in the Amazon, agents told me, that the enforcement teams rotate through Altamira for only a few weeks at a time. While there, they are tracked by networks of informants and spies so dense that even when carrying out raids by helicopter, they rarely achieve surprise.

On the afternoon in question, Luz knew just where to find them. He got off the motorbike and strode toward an agent standing guard. The agent brought him up short at rifle point. Luz raised his hands. The commander, a tightly wound man with a compressed smile, came up to confront him. Close behind the commander came another agent, masked, cradling a weapon, while a fourth agent, unmasked, stood to the side. Luz was visibly angry. He raised his smartphone to record the encounter. The video began with him booming, “…the rights of my clients!” A small group of settlers who arrived with him watched from nearby. They did not appear on camera. The commander said, “Sir, do you work for the Environment Ministry?”

Luz answered: “I am the anthropologist Edward Luz! I am here to enforce the ministerial order of Minister Ricardo Salles, whom I met last Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2020, at 14:26 in the fourth chamber of the Federal Public Ministry, where it was agreed that no property of a population in a situation of fragility will be destroyed.”

At the time, Salles was Brazil’s minister of the environment — a youthful-looking man in pale glasses who is seen to represent the far right of the rural upper classes and who, at a cabinet meeting several months later, was recorded recommending taking advantage of the media’s focus on the pandemic to “streamline” the Amazon’s protections. Nominally, IBAMA worked under his direction. Luz continued to rant. Along with two ultraright politicians, he had indeed met with Salles. Extrapolating from the meeting, he said to the commander: “Was I clear? If any property here is destroyed, you are responsible and will answer criminally!”

The commander said: “So I am being clear with you. If you do not withdraw from this territory now, you will be arrested for invading Indigenous lands.”

Luz said, “Look, we have a problem with interpretation here.”

The commander said: “No, no, there’s no problem. What is your name?”

“I am the anthropologist Edward Luz!”

“So. You, sir, are inside Indigenous land.”

“Right!”

“I’m ordering you to leave.”

“Under whose authorization?”

“If you don’t leave now, you will be arrested.”

“No! Please, what is your document? Please show me the arrest warrant!”

“You are in flagrante delicto, sir.”

Luz said: “You are a public servant of IBAMA! You do not have that authority! I’m sorry.”

“OK, then, you are under arrest.”

The agents closed on him hard. The video went shaky. As he fell, Luz could be heard saying: “I apologize! No, no! I apologize!” And also, “Keep filming!”

The Amazon forest is nearly the size of the contiguous United States. It spreads into nine countries but lies mostly in Brazil. Within Brazil, a fifth of it has been set aside for the use of Indigenous groups. Through a deliberative process involving extensive cultural surveys, those lands have been divided among several hundred reserves that collectively cover close to a half-million square miles, an expanse greater than the states of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona combined. The largest reserves are the size of midsize European countries. There are more than 200 distinct Indigenous groups, the largest of which number more than 20,000 people, and the smallest in the hundreds. Altogether, according to a 2010 census, they number about 800,000 people, if “Indigenous” is narrowly defined. Among the hundreds of groups are at least 60 like the one believed by government agencies to exist within Ituna-Itatá: extremely isolated or “uncontacted” bands that under Brazilian law are given special protections. The special status of such peoples, along with illegal land-grabbing and catastrophic deforestation, have made Ituna-Itatá a political flash point in the struggle between those who would preserve the Amazon and those who would exploit it.

The number of isolated peoples in the Amazon is not known, but it is most likely in the low thousands. For lack of contact, those who are said to inhabit Ituna-Itatá have not been counted or named by the government. Indeed, if they exist, they are so furtive that they may not realize that they inhabit their own official preserve. Nonetheless, like all Indigenous groups in Brazil, they are overseen and aided (in this case from a careful distance) by a branch of the Ministry of Justice known as FUNAI (Fundação Nacional do Índio) that is roughly equivalent to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and is staffed by civil servants, some with a taste for adventure, but none to be confused with the hard-charging agents of IBAMA.

FUNAI is the agency that created Ituna-Itatá. The reserve is wedged between two larger and older reserves whose people — the Kayapó Xikrin to the southeast, the Asurini to the southwest — occupy established villages and are attuned to the modern world. As early as the 1960s, some among them mentioned that an unknown group might be living in the wild interfluvial forests where they sometimes hunted. Though Brazil was still in the grip of a military regime at the time, it was beginning to move away from policies of forced assimilation and toward cultural accommodation. Nonetheless, for decades afterward FUNAI did nothing largely because of the area’s isolation. It was assumed that if uncontacted people lived there, the immensity of the surrounding forests would provide them with natural protection.

By the mid 2000s, however, the situation had changed. After three decades of national effort, one of the principal trans-Amazonian roads, a brutal 2,500-mile-plus east-west axis known as BR-230, was largely built, passing about 100 miles to the north. It was unpaved for long stretches and sometimes became impassible in the rainy season, but it ushered in a large new population of settlers who were devastating the forests on an unprecedented scale. The consequences to the global environment — exacerbating global warming and reducing biodiversity — were already known. From the vantage point of Ituna-Itatá, the land-grabbing was approaching inexorably upriver along the Xingu, propelled by the economic boom that resulted from the construction near Altamira of a large hydroelectric dam. The Asurini and Kayapó Xikrin were protected by the reserves that FUNAI had staked out for them, but people from both groups continued to speak about furtive Indigenous peoples in the adjacent forests. They told FUNAI that they had not interacted with the strangers but saw footprints and other clues to their existence. A neighboring homesteader added to the information. He said he had come upon “three brave Indians with long hair” who fled from his presence.

FUNAI has a division dedicated to maintaining the isolation of isolated groups. In 2009 it dispatched agents from Altamira to look around. An Asurini hunter told them of having been surrounded in the forest one night by unseen people who hurled nuts at him and ran away. Another man spoke of having come upon a temporary shelter. Eventually, the agents found footprints that, according to their Indigenous guides, were unattributable to neighboring peoples. It wasn’t much to go on, but protection of the obscure is the nature of the job, and when the agents returned to Altamira from their second foray, they filed a report suggesting the need for a temporary reserve to create a haven until further information could be gathered.

The wheels turned slowly, but in 2011 FUNAI provisionally set aside Ituna-Itatá for the group’s protection. The area’s status would have to be renewed every two to four years. The quest was then taken up by a newly arrived FUNAI investigator named Luciano Pohl, who at 38 had the strength to endure weeks in the jungle and indeed to thrive on the experience. Accompanied by a few FUNAI stalwarts and Indigenous hunters, he embarked on a series of extended explorations of Ituna-Itatá, moving by pirogue and on foot and largely living off the land. On the assumption that uncontacted Indigenous peoples are intentionally so, and that any such group would be fleeing from the oncoming settlers, Pohl and his companions pushed southward into forests so remote that they were unknown even to the guides. Pohl makes little of it now, but the effort was extraordinary. Eventually it led to the sort of evidence that Pohl was looking for: saplings hacked by unusually dull blades like those of handed-down machetes, fragments of a temporary shelter — branches bound with vines — and an area of crushed vegetation where people had bedded down. Some of the signs were fresh. It is possible that Pohl was being watched at the time. More recently, in September 2020, a FUNAI colleague of his named Rieli Franciscato was attacked while tracking an isolated group that he was trying to protect from encroaching settlers in the remote western state Rondônia. The group did not know that he was on its side. An unseen archer shot an arrow into Franciscato’s chest. Franciscato said, “Ai!” yanked it out, staggered back and died.

I asked Pohl if he had considered such risks when pushing so deeply into Ituna-Itatá. He said yes, but pointed out that greater dangers exist in Altamira, where FUNAI officials have been attacked for obstructing development, and where he himself has been threatened with death by the agents of land speculators and loggers. (Official spokespeople for FUNAI declined to speak on the record for this article.) At the time of his discoveries in Ituna-Itatá, he was mostly concerned not to expose the unseen tribe to contact, including his own. That is the biggest challenge of the job, he said: the need to gather evidence while respecting people’s desired isolation. After documenting and photographing the signs, he retreated hastily from Ituna-Itatá. He wrote up official reports that were closely held for the protection of the group and used to justify the continuation of the reserve. Pohl has come to believe firmly in the existence of the uncontacted people. He told me that after more than a decade, the fact that none have been spotted is evidence that, at least, initially, the protective strategy worked.

But now, as they invade, the settlers, loggers and land speculators scoff openly at the protections. They say that the reserve was founded on the wishful thinking of agenda-driven bureaucrats. They say that no Indigenous people reside there now, and maybe never did, and that the reserve is a put-up job by outside interests, most likely foreign environmentalists or even, somewhat illogically, the opposite: a gold-mining company with plans for an open-pit quarry. With the advent of Bolsonaro and his cabinet ministers, such views have gained the upper hand in the region. Under threat of violence, Pohl quit FUNAI in November 2020 and in 2021 relocated his family to distant Manaus.

The settlers’ local base, meanwhile, has blossomed. It is a ragged village called Vila Mocotó, which sprawls across denuded land several miles north of the reserve. Perhaps 1,000 people live there, in scattered wooden shacks and cinder-block houses. A single track leads to the settlement, several hours from the Altamira ferry crossing, and is sometimes impassable in the rainy season. Mocotó has electric power (recently brought in by the state of Pará), a diesel-fuel depot, a cafe, a school, an automotive shop, several small grocery stores, an untold number of pirated internet connections, a Facebook page and at least two Assembly of God churches. Many residents are armed and all, it seems, are angry. Agents of FUNAI and IBAMA urged me to avoid the place lest I be mistaken for an environmentalist and assaulted.

It took me two weeks in Altamira to arrange for a safe visit. As it turned out, the gatekeeper was a man with a checkered past, known to have deployed gunmen against state officials. He praised Bolsonaro and posed for a picture holding Donald Trump’s book “The Art of the Deal.” I did not argue with him. He made the necessary calls. After two forays, the first of which was defeated by door-high mud, I reached the settlement in heavy rain and, together with a Brazilian colleague, met with a group of residents — rough-looking men and women who had assembled on a veranda for our arrival. Among them were people who claimed to be recently displaced by IBAMA’s helicopter raids. They denounced their treatment and portrayed themselves as subsistence farmers trying to raise their families in a wholesome environment. I knew that the IBAMA agents did not believe them, but those were the stories the residents told. On their smartphones, they showed me videos of what they said were their homesteads being burned. One scene was set to music.

A minister pulled up a chair for a formal interview. He said that even his church had been destroyed. He mentioned that he had been on vacation at the time. I asked him if he intended to rebuild. With an audience of parishioners in attendance, he predicted that IBAMA would be forced to retreat. I may have expressed some doubt. This was not the safest approach to take in Mocotó at the time, and it seemed to anger a small group of men who had been standing together in the background. Others, however, were accepting and merely suggested that I seek out a very smart man who could explain their side: a certain anthropologist named Edward Luz.

Luz had developed a local reputation for trying to reduce the size of the Indigenous lands belonging to another group, the Arara. Luz lost the argument against them, but the settlers in Mocotó were impressed. He told me afterward that they said of him, “He’s not a leftist.”

So when IBAMA started burning buildings in Ituna-Itatá, a member of the Mocotó settler’s association contacted Luz at home in Santarém, sending him a photograph of his brother’s burned pickup truck. Luz drove to Altamira and challenged a senior IBAMA agent. According to Luz’s account, Luz said: “This is not Indian land. It is just reserved for more studies. Why are you burning houses? Can you just hold off? Can you be more peaceful?”

The agent, who prefers not to be named out of fear for his safety, remembers less-reasoned wording. When Luz predicted that someone would die — meaning anyone would or could — the agent understood it as a threat. Luz went to Brasília, where he met with Salles, then flew back to Altamira and got himself arrested in Ituna-Itatá.

On the afternoon of his arrest, Luz was handcuffed, shuttled by IBAMA helicopter to Altamira and turned over to the police. Altamira is a violent city. It is riddled with gangs and narcotics and has at times had one of the highest murder rates in the country. Gunfire can be heard most nights on the streets. Some of the police are themselves racketeers. Out by the airport stand the ruins of a small prison where in July 2019 five hours of gang fighting broke out that burned the facility and left around 60 inmates dead; 16 of them were decapitated. The guards looked on from watchtowers. Some prisoners recorded the battles on their mobile phones. As best I know, none of the videos were set to music, but one of them included narration like that of a sporting event. Altamira is that kind of place. For the police there, Luz was just an annoyance. They booked him, then released him.

But Luz was determined to maintain the struggle. Twice — immediately before and after his arrest — he barged into the local offices of FUNAI and announced that the new national policy was to stop shielding uncontacted Indigenous people and to usher them into the mainstream of modern Brazilian life. This was false and wishful thinking, but not beyond the imaginable. Bolsonaro was in the process of naming an evangelical missionary named Ricardo Lopes Dias to lead FUNAI’s department for isolated peoples — Luciano Pohl’s bureau. Dias was an especially provocative choice. Previously he proselytized for the New Tribes Mission (Luz’s childhood group), and he was notorious for later insistently intruding into the Javari Valley, an Indigenous territory near the Peruvian border that shelters one of the largest concentrations of isolated groups in the world.

Pohl was in the FUNAI office during Luz’s visits. He told me that Luz gloated over the coming appointment of Dias and was accompanied by various shady characters. Luz denies such characterizations of his companions but confirms the encounter. He and Pohl each say that on one of those visits, he demanded copies of the original reports and that Pohl refused, saying that the reports were confidential for the safety of the isolated group.

Pohl is a man of obvious courage. Other staff members in the office had been unnerved by the violence in Ituna-Itatá. Some sensed that they were being surveilled — an intuition that had to be taken seriously in those parts. When I asked Luz about this, he shrugged off their fear. Of his visits to FUNAI, he said that he had proposed a de-escalation to calm people down. But he spread the video of his arrest through social media from which it was picked up by national newscasts, where it sparked disapproving panel discussions whose tone bolstered his credentials as a defender of impoverished settlers and a consultant to the right-wing fringe. This seems to have been his calculation. He became known as “that crazy anthropologist.” Before speaking to him, I went to see a retired Catholic bishop in Altamira, an eminent liberation theologist named Erwin Kräutler, who is the author of “Indians and Ecology in Brazil” and lived under full-time police protection because of his advocacy for Indigenous rights. When I mentioned Luz to him, he frowned and asked if I knew that luz means “light.” He said a better name for the man would be Edward of Darkness.

The father of Edward Luz, whose name is also Edward Luz, heads the Brazilian offshoot of the New Tribes Mission today. The parent organization in the United States and its affiliates deploy about 3,000 missionaries worldwide. It subsists on ample donations from evangelical churches throughout North America. In 2017 it changed its name to Ethnos 360, a few years after a child-abuse scandal in its boarding schools in Senegal and the Philippines. The group was founded in 1942 by a bright-eyed Californian named Paul Fleming. who as a young man woke up one night in Los Angeles to find his mother kneeling beside his bed praying for his salvation. It seems that the experience marked him. He became a missionary, shipped off to British Malaya to save souls, caught malaria and returned to California to heal. When subsequently he helped found the New Tribes Mission, it was to bring the Gospel to all the world’s “unreached” peoples as he believed was required by the Bible to usher in Christ’s return. This remains the main purpose of the organization today. Even after the first missionaries he sent out were murdered — stabbed to death in 1943 and buried in an Amazonian vegetable garden — Fleming found the hand of God all around him.

By 1949 the New Tribes Mission had gathered sufficient funds to purchase its first aircraft: a 21-passenger DC-3, in which it began to shuttle missionaries to South America. The following year, the airplane wandered off course one night and hit a mountain in the Andes, killing everyone aboard. Months later a replacement aircraft flew into another mountain — also at night, this time in Wyoming — again with a full loss of life. Fleming was one of those killed in the crash. According to the organization’s literature, upon impact the victims encountered the bright light of Christ. Over the decades since Fleming’s death, his followers have persisted with this providential view of things. Publicly they have reacted to the coronavirus pandemic by pausing their outreach. The same was true in Brazil, the elder Edward Luz emphasized to me during a phone conversation. Another insider told me confidentially, however, that many within the group, anticipating the “end times,” privately rejoiced.

Into this mind-set, the younger Edward Luz was born in 1979 in the state of Goiás. His parents dedicated their marriage to evangelizing Indigenous people. The family moved to Santarém, a port on the south bank of the Amazon River well situated for reaching isolated peoples. There were few restrictions on such activities at the time. In 1982, word arrived of a barely known group called the Zo’é, who lived 200 miles to the north of Santarém. They numbered about 300 and inhabited settlements visible from overhead in the vicinity of two small rivers in an inaccessible forest. They were so isolated that they barely needed a name for themselves, Zo’é meaning “true human.” Previous fleeting encounters showed that they wanted to be left alone. The New Tribes Mission Brazil decided to go after them. By 1985 the senior Edward Luz had built a station two days’ walk from the Zo’é settlements. It included some wooden buildings and a dirt runway that allowed for supply flights from Santarém. He called it Esperança, or “Hope.”

I heard from his son that he saw himself as progressive. He learned Indigenous languages. He enjoyed Indigenous foods and appreciated Indigenous ways. He did not object to nudity among Native peoples. He hoped to persuade them someday to assume the burden of spreading the Gospel among themselves. Yet because he could not accept the tribe’s isolation, he provoked its decline. This became obvious after 1986 when the Zo’é stopped being shy. A band of them materialized at the mission station, planted a manioc garden and built an encampment nearby. The following year, the younger Edward Luz, the future anthropologist, arrived for the first time. He was 7. He sat in the back of a single-engine Beechcraft looking down at the uninterrupted forests below, wondering what exception to the foliage might allow the airplane to land, and then, during the descent into Esperança, with trees flashing by the wingtips, wondering how the airplane could survive such a narrow runway. Afterward, he spent the first of several long stays with his family at the station. He made friends with Zo’é children and began to learn their language. He now calls that experience the greatest privilege of his life.

But all was not well with the Zo’é. At the mission station and in their forest settlements, many grew sick and died from flu and malaria. At first this posed less of a burden to the New Tribes Mission than might be expected, perhaps because the organization was focused primarily on the Zo’é’s afterlife.

Brazil, meanwhile, was moving in new directions. An early sign appeared in 1978, when an attempt by the military regime to offer up Indigenous lands to free-market forces (the so-called Indian Emancipation Decree) provoked urban protests against the abuse of Indigenous peoples. Seven years later, following waves of unrelated street demonstrations, the dictatorship was forced from power. The change stripped the New Tribes Mission of a useful alliance, and three years later exposed it to the new national constitution — the one that remains in effect today and mandates protections for Indigenous groups. With Zo’é deaths outstripping religious conversions, Luz turned to FUNAI for medical help if perhaps only to buy time. Shocked by the abysmal conditions they encountered upon arrival, FUNAI officials soon shuttered the station and banned the New Tribes Mission from returning. (New Tribes Mission Brazil denies this version of events.) FUNAI installed a medical clinic to handle the immediate crisis and encouraged the Zo’é to embrace their earlier isolation. The Zo’é never quite did, but eventually they gained a territorial reserve and slowly rebuilt their population. The elder Edward Luz moved to other pastures, and with him went his family.

Among the toxic legacies of Brazil’s former military dictatorship, only deforestation in the Amazon still threatens the world. To the extent that its effects spread into the global atmosphere, it has raised doubts among environmentalists about the very validity of national sovereignty — particularly that of Brazil. This is paradoxical because the military leaders were, to a man, ultranationalists. Large-scale deforestation dates back 50 years, to the early 1970s, when Brazil’s economy was booming partly because of its investments in totalitarian-style megaprojects — monumental bridges, dams, divided highways and a whole new capital city. These were seen to reflect Brazil’s modernity. To the military mind, the Amazon forest was a vulnerability and a void. As part of a new national “integration” plan (“Integrate not to forfeit!”), the generals resolved to conquer the wilds in imperial style, by building roads.

At the top of the plan was the Trans-Amazonian Highway, the 2,500-mile lateral that parallels the Amazon River south of its course and feeds through Altamira before proceeding toward the Peruvian borderlands, days of rough travel to the west. This is the road, still largely unpaved and incomplete, that passes 100 miles above Ituna-Itatá and has ushered in so much destruction and conflict there. In a sense, the generals meant it to do so from the start. Accompanied by an offer of small homesteads, the road was intended to provide Brazil with a social outlet, relieving economic and political pressure primarily from the country’s parched northeast, which had long been feared by the military government for its revolutionary potential. The regime promoted the Amazon as “a land without men for men without land.” The claim was untrue, and soon the homesteading plan was riddled with problems. But over the years, tens of thousands of people answered the call and came down the road anyway. Most of the newcomers were very poor. Once they arrived, they found ways to stay.

Many who failed at homesteading ended up in Altamira and a string of smaller towns. Others remained in the forest as hired hands and subsistence farmers. At first their clearings were confined to the proximity of the main roads, but as side roads proliferated and land speculation and corruption grew, the invasion got out of control. By the late 1980s, it seemed for the first time that the very existence of the Amazon might be threatened unless a sufficiently large network of self-policing Indigenous reserves was established. Self-policing would be the key, which in turn would require the legitimization of special Indigenous rights, if not necessarily of cultural preservation. But such niceties went largely unheeded by powerful forces in Brazil.

The generals were pushed out in 1985, and the constitution of 1988 cemented the new democracy and guaranteed Indigenous rights, but every successive civilian government — left, right, reformist, reactionary — continued with the road building and policies that furthered the destruction of the forest. Indeed, it was under the first civilian government (led by President José Sarney) that a military-era hydroelectric project to dam the Xingu River at the Belo Monte cascades, downstream from Altamira, was put forward. This was to be one of the largest dam complexes in the world. The design required the creation of 700 square miles of holding reservoirs, energy banks that would drown untold numbers of trees, disrupt the riverine ecosystem, bleed methane gas into the atmosphere, flood Indigenous lands and profoundly disturb the lives of many thousands of inhabitants, including Luciano Pohl’s future guides, the Asurini and the Kayapó Xikrin.

In protest of the initiative, Kayapó from a number of regions staged a media spectacle. Known as the Altamira Gathering, the event took place across five days in 1989 in an Altamira community center. It featured 600 representatives from as many as 40 Indigenous groups. The participants performed ceremonies and made speeches. Many dressed traditionally in colorful feathers. Reporters, camera crews and advocates flew in from abroad, as did politicians and celebrities, most notably the British musician Sting, who had allied himself with an upstream Kayapó leader known as Chief Raoni Metuktire, and later toured Europe and the United States with him.

As a consequence of the Altamira Gathering, the dam initiative was forced into a decade of delays, resulting in an inefficient run-of-river redesign that accepted seasonal fluctuations in the Xingu’s flow and, with it, reductions in electrical-generation capacity for roughly half the year. Eventually, the structures were built. In aggregate they were completed in 2019 as one of the world’s largest dams, diverting most of the Xingu’s dry-season flow into excavated channels that feed the generators’ turbines and leave 60 miles of the riverbed largely denuded of water, interrupting the river’s ecosystem and threatening the natural balance of the region. A consensus exists that however spectacular the Altamira Gathering may have seemed at the time, the completion of the dam meant that the protests had proved ineffectual and that the Kayapó had been disregarded as usual.

But alternative understandings are possible. An argument can be made that for the Indigenous groups who were not directly dependent on riverbank living, the gathering was in the long term a success. It taught lessons about the power of spectacles, the ease with which the press could be enlisted, the sympathy that resides overseas, the potential for funding and, most crucial, the need to frame initiatives within the views of foreign advocates. These were homegrown Amazonian insights, but they were noted within academic circles abroad, where a dynamic new field of anthropological inquiry, the study of “dressing up” — of the importance of costume and adornment — was born. The seminal thinker was a longtime observer of the Kayapó, the late Terence S. Turner of the University of Chicago, whose article “The Social Skin” helped shape the field. He started as a conventional anthropologist, coolly observant of his subjects, but gradually began advocating for the groups he studied. He attended the Altamira Gathering. Afterward he promoted the idea of Kayapó-made video productions to reinforce Kayapó culture. The Kayapó embraced the idea to the extent of developing a distinctive cinematographic style that involves extensive use of wide-angle lenses and drones. To simplify history, the Altamira Gathering became an exercise less in Indigenous pride than in Indigenous power and, unexpectedly, in assimilation. Through stage-managed displays of tradition, during those five days the Kayapó joined the modern world.

Edward Luz was 9 at the time and enjoying his visits to the Zo’é station. He knew of road-construction projects somewhere far away in the Amazon, but nothing of the Belo Monte dam, the Altamira Gathering or the gathering strength of Indigenous rights movements worldwide. For him the 1990s slid by in the immediacy of childhood and the certainties of his parents’ faith. In 1998 he turned 19. His mother wanted him to become a medical missionary. Instead, he went off to the University of Brasília, where he discovered the field of cultural anthropology. In the evenings he attended a Baptist seminary, where he dutifully pursued a parallel degree. But he began to change. To me, he said: “When I found anthropology, I found myself. It was a science I was so curious about: the Indians, how they live, what they believe.” I asked him if he had lost his religion. He said: “I don’t know if you know someone who really believes. Believes in Christ. Believes in heaven and all the prophets. My father is just like that. I did not choose to be born in a missionary house. But I had to live with my parents’ religion.”

He finished with the seminary in 2003, graduated from the university the same year and proceeded into graduate studies in anthropology. He became an all-in academic. He frequented symposia. He wore T-shirts emblazoned with Che Guevara. He did not mention his missionary background. He said to me: “I recommended to my dad not to work with isolated tribes. Not to reach out to them. Because it is too much responsibility. Heaven can wait, OK?”

For his master’s thesis, Luz went to Tocantins in 2004 to study the Xerénte, a group that spoke Portuguese widely and had long been in contact with the outside world. The Xerénte had previously been studied by a Harvard anthropologist named David Maybury-Lewis, who founded the Cambridge-based advocacy group called Cultural Survival, which emphasizes Indigenous peoples’ economic empowerment and self-determination, and who was responsible for persuading Terence Turner to work among the Kayapó. Maybury-Lewis was an activist, as both Turner and Luz were to become — all three of them insisting on the inherent modernity of Indigenous groups, though ultimately for opposite political ends. Having settled on studying one of the more assimilated groups in Brazil, Luz concentrated his research on the small number of traditionalists among them who clung to aspects of their foundation myths, albeit modified to accommodate the arrival of Europeans. He saw his role as helping the Xerénte shore up their defenses against the onslaughts of big commercial farmers who were steadily approaching with their huge tractor-tilled fields. To me, he said, “I thought this is exactly what I want to do with my life.”

His Xerénte informants were dualists whose world consisted of paired oppositions: the sun and moon, day and night, woman and man, good and evil. He says they told him that they were the children of the sun and that before the Portuguese possessed technology — the guns, the clothes, the cars, the computers — the sun offered it first to the Xerénte. The Xerénte said, What is that? The sun said, It’s a rifle: You can kill whatever you want. The Xerénte fired the rifle and were surprised by the noise and smell. They said obviously we don’t want this device. So the sun gave the rifle to the moon, and the moon gave the rifle to the Portuguese. The sun also offered clothes to the Xerénte. The Xerénte began to wear clothes, but the clothes soon smelled and grew scratchy, so the Xerénte gave them back to the sun, and the sun gave them to the moon, and the moon gave them to the Portuguese. And so on. Luz says he heard the story several times. After each recounting, old women came to him and lamented the decisions that their ancestors had made. “How stupid we were in the past! If we had accepted the technology, we would be rich now and the whites would be a poor tribe like us. They would be hunting like us, and we would be traveling by car!”

This was not a theme that Luz wanted to hear, but he came to see it as their legitimate choice, and it resonated with memories from his childhood. He told me: “I realized that these people were not fighting development. They had cellphones and wore new bluejeans and sunglasses. And I was walking around in T-shirts with heroes of the revolution on them, thinking I could help keep capitalism from continuing to destroy their tribe. But the Xerénte were thinking the opposite. They wanted to make up for lost time.”

People who worked with Luz then remember him as a promising field researcher but an unusually private one. Luz kept his doubts to himself — “I did not want to mess with the establishment,” he told me. An influential professor who wishes to remain anonymous now because of the increased polarization of Brazil under Bolsanaro recommended him for a doctoral program. Luz took a temporary contract job with FUNAI to travel to the upper Solimões River, near the border with Peru, and perform the cultural surveys necessary for the demarcation of three new Indigenous reserves. He said, “I felt like a hero because I was helping those guys to live like Indians.”

In 2005 FUNAI gave him another temporary job, to go back to the upper Solimões and adjudicate Indigenous claims that had been vouched for by another contract anthropologist. This time it did not go so well. Luz came to believe that the claims were fraudulent or inflated, and he wrote them up as such. He says that he was disappointed by what he found, but he continued with his studies.

Two years later FUNAI dispatched him once again on a survey mission, this time as a team leader tasked with creating a large new reserve on the Rio Negro. It was 2007, long before Luz first heard of Ituna-Itatá. He was 28. The team was to be based in Barcelos, a former colonial capital 270 miles upriver from the Rio Negro’s confluence with the Amazon at Manaus. The town was the urban core of a huge municipality of the same name — 47, 288 square miles of rivers and rainforests inhabited by numerous Indigenous groups whose historical presence was well documented. Prominent among them were the Baré and Warekena, who lived in dispersed villages along the Rio Negro and its northern tributaries. These people had been brutalized for centuries, and many had lost their traditional beliefs and language.

Luz told me that he approached the project knowing that the claims were indisputable, as was the need for restitution; he said that after the earlier disappointments he viewed the Barcelos assignment as a way to legitimize himself within the anthropological establishment. But his final FUNAI supervisor, who came aboard partway through the effort, told me that she believed he had secretly opposed special government assistance from the start. Asking that I not use her name out of fears for her personal safety, she said, “His work was bad work,” meaning she thought it was biased. She added: “He took a position against those people. This is a complicated subject because he does not understand who the Indigenous are and how many were forced to hide their identity to survive. But Edward Luz is a missionary. He is trying to get the missionaries back onto Indian lands.”

Luz denies being a missionary and told me that he did not mean to make trouble, but that the first meeting in Barcelos proceeded awkwardly when he laid out unmarked topographical maps and the Indigenous representatives countered with an electronic satellite image of the forest on which they had superimposed their request. He says it was an enormous expanse almost as large as the nearby Yanomami reserve (at the size of Indiana, one of the largest in Brazil) and included the city Barcelos. This was probably just an opening gambit, but Luz was shocked. He said, “Wait, you also want the city of Barcelos?”

“Yes,” they said.

According to Luz, the representatives reasoned that Barcelos had been an Indigenous village before becoming a colonial capital. They also argued that most of the city’s current residents were Indigenous. Surveys showed that since the year 2000 the declared Indigenous population had indeed rapidly increased, while the number of non-Indigenous residents (known to some as neo-Brazilians) had leveled off. This raised the question of definitions. A Brazilian sociologist named Sidnei Clemente Peres has written extensively about the connection between new territorial demarcations and ethnicity in Barcelos and has made the case that the prospect of reparations has enabled previously oppressed groups to renew their collective life and reaffirm their identities. As a scholar, Luz might once have made a similar case. How Indigenous do you have to be to be Indigenous, and how is Indigenousness measured? How long must your ancestors have inhabited a patch of the world for you to take possession of it now? If you currently live in the manner of neo-Brazilians, should that disqualify you? And what is the measure of the manner? Reasonably enough, FUNAI relies on judgment, compromise and negotiation. In Barcelos this turned out to be difficult for Luz to provide.

To me, he said, “I realized that in the city, there was no difference between the ‘Indians’ and other Amazonian citizens.” Using a sometimes derogatory Brazilian word for the mestizos of mixed Indigenous and European descent who constitute the majority of the Amazon’s residents, he said: “This is caboclo territory! You lived for centuries as caboclos. Why now do you want to be an Indian?”

Luz returned to Brasília empty-handed and submitted a report to FUNAI in which his skepticism showed through. His FUNAI supervisor terminated the agency’s relationship with him and dispatched a replacement team to patch things up. Luz admits that he failed in Barcelos, but he blames the local residents, not his refusal to compromise.

Two years after returning from Barcelos, he spoke publicly about his perceptions. It was 2009. He went to the Brazilian Congress and described his suspicions of fraud. Initially, his message interested only the extreme right wing: disciplinarians who yearned for the former military regime; evangelicals called the Three Bs for Bible, bullets and beef; oppressive farmers known as ruralistas; and a group of fascist Catholics in a movement called Tradition, Family and Property. These groups overlapped. They saw Indigenous peoples as obstacles. Bolsonaro once went on record asserting that in the 19th century, the United States cavalry had done things right. Today’s Brazilian Army cannot now do the same, but if the Indigenous peoples could be absorbed into the mainstream of society, the conquest of the Amazon could proceed unimpeded. With his warnings about fraud, Luz played into that thinking. His university colleagues looked on in surprise. He says he believed that he was politically neutral. He criticized the academy for stylish thinking and the field of anthropology for paternalism.

His initial objections were mostly confined to his area of expertise: the procedures used by FUNAI to conduct its surveys. Lengthy guidelines including cultural and linguistic studies, historical studies and archaeological evidence mandate the process. But Luz came to believe that the process was often politicized and arbitrary. In 2010, at a congressional hearing in Brasília, he went further, questioning the formation of a certain Indigenous reserve and proposing what he called “technical reforms” to how such territories were granted. He maintained that his colleagues had fallen for a “sacred story” — that Indians will preserve the forest and are environmentalists by nature — but that this was in fact a lie. To me, he said: “My colleagues would not speak to me anymore or even be seen in my presence. It was as if I had become radioactive.”

Luz left the Brazilian Anthropological Association, which issued a statement emphasizing that he did not speak in the association’s name. Luz retorted that of course he did not speak in the association’s name. He said the academics wanted to keep Indians in the past and treat them as if they were animals in a zoo. Bolsonaro had used similar language but to insult Indians as less than fully human. Luz expected people to accept his claim when he said that his own meaning was different.

He went home to Santarém in 2010 and set himself up as a consultant — an independent anthropologist with an unfinished degree and no clients in sight. For Luz, his beliefs were affirmed when a delegation of Zo’é leaders traveled the following year to Brasília to demand less isolation, not more. He acknowledged that the Zo’é had suffered grievous injury from contact with his father and the New Tribes Mission, but of the Indigenous as a category, he said: “They are tired of being poor. They are tired of living by making manioc flour, fishing and hunting. They realize that they can have much more. Many of them have smartphones and internet, and they can watch videos. They see that Indians in the U.S. and Canada — they have oil wells, mining.”

I answered skeptically, “Some do.”

He mentioned that the Seminole Tribe in Florida owns the Hard Rock empire. He said: “The people here see that North American Indians can be rich. Maybe they are not rich, but they can be rich. And our people ask: ‘And we are condemned to poverty? Is that our fate?’ Brazil has to start listening to what they are saying. ‘We have our land, we have our resources, we want to exploit them!’” He added, “I don’t know if I make myself clear?”

I said that he did but noted that many of the assimilated Indigenous peoples in Brazil have dispersed into the country’s urban slums and that some have been reduced to sheltering in cardboard constructs beside country roads. “Isn’t it possible that some want to join the modern economy and others do not?”

“Yes, of course,” he said.

Luz mentioned the Yanomami, who say that the sky will fall if it is overcome by a smoke they call shawara that emanates from mining. Luz told me that he believes their thinking should be respected. He said: “The shawara is their cosmology, their apocalyptic mythology. OK, that’s very comprehensible to me. I have mine, you have yours, they have theirs. But ask a Kayapó on the Xingu river or a Munduruku on the Tapajos. Ask them about gold mining. They have wanted to mine their land for the last 30 years.”

This has been true for some, not all.

He went on: “Tribal mining has been outlawed as one of the original conditions on Indigenous reserves. But they are no more stupid than you and I. They know what precious metal is. They know what gold is. They follow the market on their smartphones. They’ve watched ‘Gold Rush’ on the Discovery Channel.”

As Luz puts it, the Amazon is a rich but impoverished place. The dilemma is simple and intractable. Despite its size, the forest cannot accommodate all the demands that are placed on it. It may endure in patches on some hard-fought reserves, but elsewhere it will disappear. In its place will come homesteads, followed by consolidated properties, followed by denuded scrublands with dirt roads that turn muddy among mines that scar the earth. The pressures are overwhelming. The anecdotes swing to extremes. The struggle over Ituna-Itatá dates back to a time, more than a decade before Edward Luz roared into the clearing to confront the agents of IBAMA, when the forest had been cut down for miles around Anapu, a lawless settlement on the Trans-Amazonian, and territorial clashes were common. The most violent of them lay an hour to the south along the receding frontiers where subsistence farmers were invading forests on behalf of wealthy speculators filing fraudulent claims. The claims formed redundant grids on a confusion of maps, eventually including those that covered the lands of Ituna-Itatá. Forged deeds that needed to look historical were aged in boxes containing crickets that chewed the documents’ edges and defecated on the sheets — an art form known as grilagem (from grilo for cricket) that is widely practiced in rural Brazil. Around Anapu, early land claims soon achieved legacy status within established families, and new ones bred raw emotions. It was easy to guess which of the invading homesteaders worked secretly for the land-grabbers. They were the ones who were not being brutalized. Legitimate homesteaders had to band together to keep their equipment intact and their buildings from being burned by thugs.

When the government of President Lula da Silva, a left-wing populist, revived the plan for the Belo Monte dam in 2010 — this time unstoppably — Altamira boomed with workers seeking construction jobs. Then as now, illegal logging led the invasions, bulldozing primitive roads deep into previously untouched territory in order to harvest the rare hardwood trees called ipé, whose extraction opened the way for the wholesale logging and ranching to come. Given the obviousness of the logging roads (which necessarily cross reserve perimeters after approaching from the outside), you would expect that they would stop at the edge of the Indigenous reserves, where logging is strictly forbidden, but often they do not.

I set off with an IBAMA patrol that passed along a newly cut road within view of an Indigenous village. We followed the road 20 miles into a reserve to an illegal logging site from which a crew had just fled, leaving behind a fortune in felled ipé trees. The IBAMA agents expressed frustration about lacking the heavy equipment necessary to confiscate the logs or even sufficient personnel to guard the site. Inevitably the illegal loggers would return after hours and haul away the treasure. It was impossible that the Indigenous residents did not know. When I expressed surprise after my return, Luz called me naïve. He said: “If illegal loggers are caught by IBAMA, they get arrested. If they’re caught by Indians, they get killed. So what do you think? No one is logging on that territory without Indian permission.”

I thought he might be simplifying matters, and I mentioned it to an anthropologist of outstanding authority, an emeritus professor of the universities of Chicago and São Paulo, Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, who is the former president of the Brazilian Anthropological Association and was instrumental in writing the Indigenous rights clauses into the constitution. Da Cunha is familiar with the Kayapó, a former student of Claude Lévi-Strauss and highly respected in Brazil today. She is a formidable opponent to Luz and his clients. She disagreed with his portrayal but did not summarily dismiss the idea that corruption exists on Indigenous reserves.

To paraphrase her, she said, look, this is Brazil.

She said: “In mining — in gold, in diamonds, in logs — there is always an attempt to co-opt Indigenous people. Corruption is always part of the story. Men are more easily co-opted than women” — some tribesmen, for example, have been recruited by illegal gold miners, or garimpeiros, to allow work on their land — “There is always an attempt. But there is also resistance.”

It is well known, for instance, that logging trucks regularly emerge from the Kayapó-Xikrin reserve hauling illegally harvested trees to the sawmills in Anapu. To combat these incursions, some in the same Kayapó group disseminate videos of its members defending their territory with armed patrols that confront gold miners and settlers, tear down their structures and frighten them away. The Kayapó’s historic reputation as warriors is now mostly obsolete, but it may help them in their defense. Da Cunha’s hope is that the constitution has provided a structure that allows for such efforts sometimes to succeed.

The rate of deforestation in the Amazon has varied with the ebbs and flows of the Brazilian economy, hitting a low point about a decade ago. Luciano Pohl told me that in 2012 he found only one homestead inside Ituna-Itatá and in 2013 only a few but that greed for land there was so intense that by 2016 the property maps of the reserve were smothered in fraudulent claims, many of them overlapping and rampantly illegal. The claimants tended to be local opportunists of limited means but raw ambition. Their claims were less absurd than they were cynical. They followed a tested Brazilian principle that illegality often leads to law.

Pohl was disgusted. He told me that in late 2016 after the left-wing president Dilma Rousseff was removed from office (nominally for her proximity to corruption; Pohl calls it a coup d’état) and Bolsonaro’s establishment predecessor Michel Temer temporarily assumed her place, the illegal assertion of titles in Ituna-Itatá escalated. According to Pohl, a new crowd shoved aside the first generation of claimants, beginning the systematic invasion of the land and building Mocotó into a logistics base primarily for the maintenance of heavy equipment and the distribution of diesel fuel. I asked Pohl to consider that these were merely the actions of the poor, squatting on land as they have for generations elsewhere in Brazil in desperation to survive. He emphatically contradicted that, saying the invasion of Ituna-Itatá was the story of profound political corruption, financial corruption, moral corruption and calculation.

Pohl received his first death threats not long after a municipal environmental official named Luiz Alberto Araújo was assassinated on Oct. 13, 2016, while sitting in his car at home in Altamira, in the presence of his family — shot seven times, then for good measure twice more, supposedly for having tried to block development schemes. The killers arrived and left on a motorcycle and were never found.

Surveying Ituna-Itatá became increasingly dangerous. Pohl told me that a riverbank logistics depot was guarded by men armed with rifles, themselves fearful of calling down the wrath of Amazonian warriors if they angered Indigenous guides. According to him, if IBAMA approached the depot at all, it was only by overflight. When Bolsonaro won the election in 2018, the land-grabbers went rushing by the thousands into the old-growth forests, where they encountered no Indigenous opposition, either because the native residents had fled or because they had never existed in the first place. Ituna-Itatá became a free-for-all, the most heavily invaded reserve in Brazil; from August 2018 to July 2019, it accounted for 30 percent of the deforestation within Indigenous lands. Across the Amazon, land-grabbers cleared so much territory so fast that during the accompanying dry season of July and August 2019, when they set fire to the bulldozed debris, the ensuing smoke caused day to turn to night in distant São Paulo and made international news that the jungle itself was burning. Given the extent of deforestation, it might as well have been.

The pattern repeated in 2020 to an even greater degree, augmented by enormous wildfires in the Pantanal grasslands to the southwest of the Amazon basin. Early that year Covid-19 was known to be approaching, but it had barely touched down in São Paulo and had not yet entered the forests when IBAMA, despite the ascent of Bolsonaro, the agency’s mortal enemy, decided to proceed according to its still-standing mandates and take action against the radical encroachments in Ituna-Itatá. Given that IBAMA’s helicopter campaign ran counter to Bolsonaro’s desires, the surprise was that the agents were able to draw it out for months. It was not, however, destined to succeed.

The video Luz took of himself turned out to be effective. After his release, he sought out the senior IBAMA agent, this time at the agency’s Altamira base, and said: “Do you know why I am trying to get you to stop burning houses? Do you even have a clue?”

“Ah, because you work for the farmers. We know who you are.”

“Man, I think you should rethink your view. I am here because your fires are doing nothing at all. Those settlers will not leave. Because many of them have no place to go. They will never go away. And they will continue to clear the forest to survive.”

Over the period that followed, Luz’s efforts spread through the Brazilian political ether, exciting scorn among environmentalists and mainstream commentators on television but also in no small measure eliciting sympathy and admiration from the right-wing forces in power. In Ituna-Itatá, Luz got what he wanted. IBAMA was withdrawn from the reserve, and the principal agents were demoted or fired as Bolsonaro’s administration wreaked vengeance against them for their attempts to enforce the law. The pandemic arrived at about the same time, decimating the remnants of environmental defenses and pushing Indigenous groups deeper into the reserves. Much to the gloating of the right wing, the unseen Indigenous peoples of Ituna-Itatá remained unseen.

In December 2021, as required by Ituna-Itatá’s provisional status, a FUNAI investigator produced a report that recommended that the territory should remain protected, as there continued to be evidence of the existence of an isolated tribe. This was predictable given the hard work that FUNAI had done on the ground. In late January of this year, despite a judicial decision affirming the territory’s protections, FUNAI headquarters in Brasília disagreed and announced that after 11 years of failing to conclusively find an isolated tribe, it was time to remove Ituna-Itatá’s special status. This was predictable given the proximity of FUNAI’s leadership to the Bolsonaro administration. Federal prosecutors of the famously independent Ministério Público Federal appealed and, following another judicial order in early February, FUNAI was forced to reverse itself and extend the area’s protections, but only by six months.

It seems hardly to matter anymore. About two years have gone by since the practical collapse of restraints, and in the decimated shell of the Ituna-Itatá reserve, as in much of the Brazilian Amazon, deforestation has resumed in full force. The next dry season is fast approaching and the fires seem sure to intensify as one sort of burning is replaced by another.

William Langewiesche is a contributing writer for the magazine. He is a former national correspondent for The Atlantic and international correspondent for Vanity Fair, where he covered a wide variety of subjects throughout the world. João Castellano is an independent photojournalist working for Brazilian and international media since 2007.