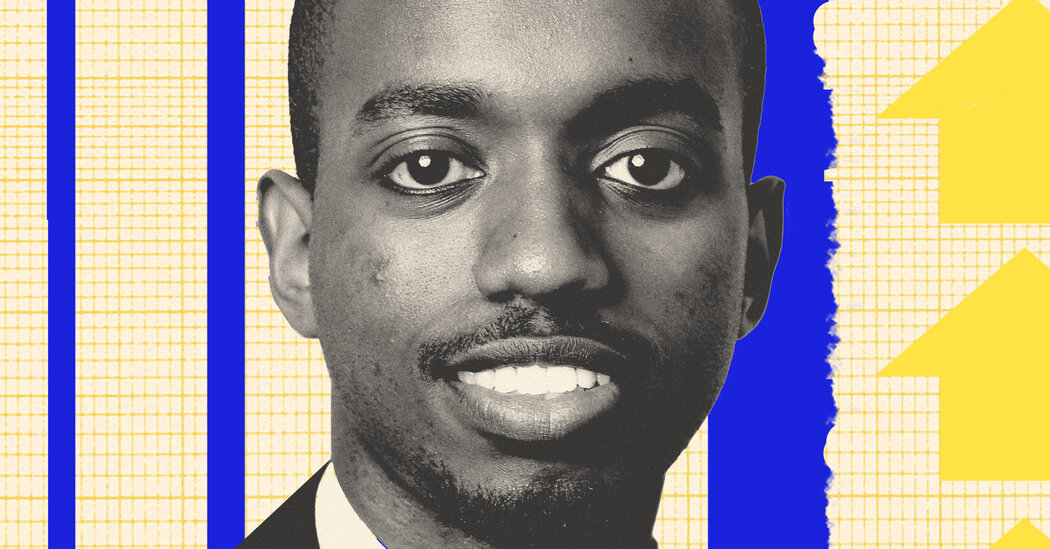

Fred Mutsinzi grew up in Rwanda, moved to the United States for college, then wound up homeless in Portland, Maine, after his money ran out. In 2014 he scraped together the funds for a bus to Boston, where he sold merchandise to tourists from a cart. That is when his life changed.

“I saw a young man my age, a Black man, maybe early 20s,” Mutsinzi recounted recently. “I asked him, ‘You seem successful. You’re in a suit.’ He said, ‘I’m in a school.’ I said, ‘Why are you wearing a suit?’ He said, ‘I do this program called Year Up.’”

Year Up, as Mutsinzi discovered, provides six months of tuition-free job training and then places its trainees in six-month internships with major employers such as Amazon, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase and Microsoft. Those internships frequently lead to job offers or college admissions. Year Up, which began in 2000, is designed for low-income high school graduates who are 18 to 26 years old (up to age 30 in some locations). Year Up says that 83 percent of its graduates are working or enrolled in school within four months of graduation from the program and that the average starting salary of those who are working is $44,000.

Mutsinzi went through the Year Up training, found work in finance, and this week, at age 27, began a job as an investment analyst for a venture capital firm in Boston specializing in early-stage investments in robotics and artificial intelligence. (The company is in stealth mode ahead of the planned introduction of its first fund in March, so I’m not naming it.) “It’s going great,” Mutsinzi told me on Thursday. “I’m really enjoying it. I’m learning a ton.”

It’s an inspiring story. There is, however, a problem. Year Up is too small to have a large-scale effect on the unemployment and underemployment of disadvantaged youth in the United States. It has served about 34,000 students since it began. It plans to serve about 4,900 students this year and about 7,200 by 2025. By contrast, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data released this morning, there were over 1.7 million unemployed Americans aged 20 to 29 in December. The December unemployment rate for high school graduates aged 25 and up was 4.6 percent, compared to 2.1 percent for people 25 and older with bachelor’s degrees or higher. What’s more, millions of Americans who do have jobs are stuck in low-wage work because they lack the skills or opportunities to advance.

Mutsinzi recognizes the scale problem. So does Gerald Chertavian, the founder and chief executive of Year Up and a former Wall Street banker who built and sold an internet marketing company, Conduit Communications. Year Up says it has an annual operating budget of more than $170 million, and that figure doesn’t include the spending by the blue-chip companies that take its trainees.

“Right now we’re growing linearly,” Chertavian told me recently. “The question is, how do you take this from a linear growth model to an exponential growth model?”

The answer: not easily. Year Up costs a lot because it aims high. It takes young men and women who are at risk of being stuck at the bottom and puts them on a path to the middle class. Cutting back too much on the coaching and mentoring that students get could render it ineffective. “We’re putting a huge amount of time and effort into holding what we know works, the special sauce, but innovating new models that are faster, that require less philanthropy per student,” Chertavian said.

One solution that Year Up is experimenting with is to outsource the teaching of hard skills — such as proficiency in Microsoft Office — and focus on the “special sauce,” which is Year Up’s inculcation of soft skills such as showing up on time, meeting deadlines and working in teams. The sorts of things students learn, Chertavian said, are: “How do you make small talk when you’re in the elevator with someone? What does proactivity look like? What does it mean to take initiative?”

Year Up is also experimenting with shortening the six-month training for some people. “We have to meet the students where they are rather than say everyone goes through the exact same programmatic experience,” Chertavian said.

For older workers, Year Up has developed a program called Grads of Life, which helps companies gear their hiring and promotion practices for diversity, equity and inclusion. One thrust of the organization, which operates as a subsidiary, is getting companies to relinquish their insistence on bachelor’s degrees for jobs that don’t truly require them.

I asked Mutsinzi for his thoughts about Year Up. His story is colorful. He decided to attend a small Christian college in Oklahoma even though he had essentially no money and only a partial scholarship. He thought he might earn the rest of the tuition by playing basketball, but he wasn’t good enough. A friend told him about a community college in Maine so he transferred there, not realizing that there were also community colleges in Oklahoma. He studied in Maine for two years but again ran out of money. Then came Boston and Year Up.

Mutsinzi is smart and charismatic and managed to impress some influential people along the way. Seth Klarman, the billionaire co-founder and chief executive of the hedge fund Baupost Group, invited him to his office, where they talked for an hour. Mutsinzi had an internship at JPMorgan and converted it into a full-time role, then moved to KPMG and later Cambridge Associates. Over this period he earned a bachelor’s degree online through Southern New Hampshire University and put on charity basketball tournaments to benefit Year Up, raising, he said, about $100,000.

Mutsinzi said that he agrees with Chertavian that for some people, the six-month training program can be sped up. He also agrees with Year Up’s cost-saving initiative of moving more of its training out of expensive downtown office space, affiliating with community colleges and using space there.

Most of all, he said, employers should open their minds to hiring people who don’t check all of their boxes. (I’ve written about this before.) He’s still thankful to a manager at KPMG who made an exception and gave him a full-time job even though he hadn’t completed his bachelor’s degree. “I was already there, doing a good job,” he said. “It’s really absurd that they would have required that piece of paper.” (“KPMG has made its degree requirements for certain positions more flexible in recent years,” James Powell, the national partner-in-charge of university talent acquisition for KPMG, said in a statement released to me today.)

Good employment matches require serious effort and fresh thinking by both students and employers. “Year Up is almost a hack to a broken system,” Chertavian said. “You’d want to change the system.” He added: “It’s partly consciousness-raising. If we can change people’s beliefs, we have a shot at changing their behaviors.”

The readers write

For all the attention paid to the recent and short-lived out-performance of the stock market’s largest stocks, as you mentioned in your newsletter on Wednesday, the longer story is very different.

As this chart shows, the average stock in the S&P 500 has outperformed the better-known size (or cap-weighted) benchmark since the tech bubble of 2000. Investors might consider this before they give up on portfolio diversification.

Daniel P. Wiener

Newton, Mass.

The writer is chairman of Adviser Investments.

Quote of the day

“The mainstream profession seems to be following the path of the Spanish Habsburgs and not controlling inbreeding of close intellectual relatives.”

— David Colander, “Intellectual Incest on the Charles: Why Economists are a little bit off,” in Eastern Economic Journal (2015)

Have feedback? Send a note to coy-newsletter@nytimes.com.