Everything is going great for the James Webb Space Telescope. So far.

Astronomers are starting to breathe again.

Two weeks ago, the most powerful space observatory ever built roared into the sky, carrying the hopes and dreams of a generation of astronomers in a tightly wrapped package of mirrors, wires, motors, cables latches and willowy sheets of thin plastic on a pillar of smoke and fire.

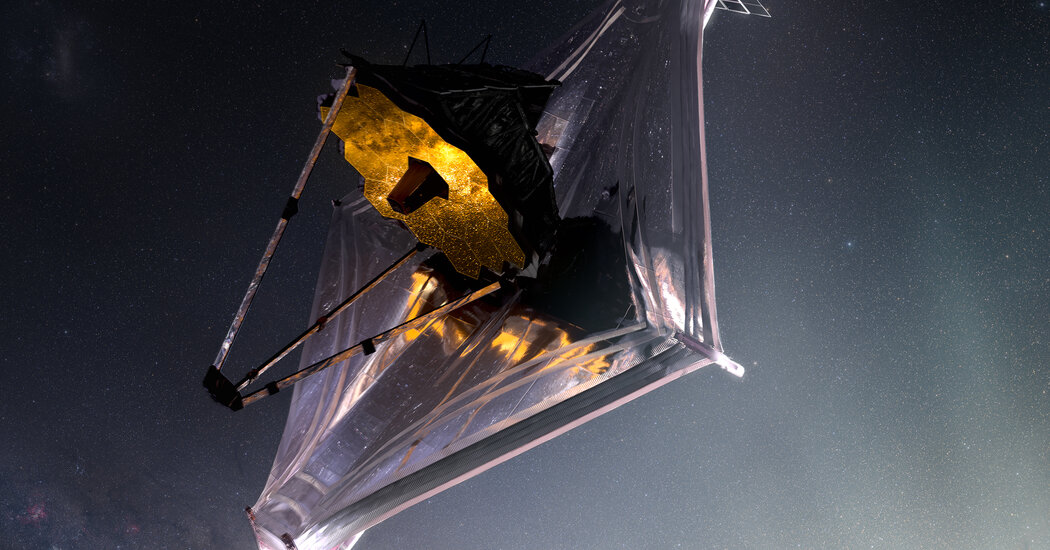

On Saturday, the observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope, completed a final, crucial step around 10:30 a.m. by unfolding the last section of its golden, hexagonal mirrors. Nearly three hours later, engineers sent commands to latch those mirrors into place, a step that amounted to it becoming fully deployed, according to NASA.

It was the most recent of a series of delicate maneuvers with what the space agency called 344 “single points of failure” while speeding far away in space. Now the telescope is almost ready for business, although more tense moments are still in its future.

“I’m emotional about it,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s science chief, said of all the telescope’s mirrors finally clicking into place. “What an amazing milestone — we see that beautiful pattern out there in the sky now almost complete.”

The James Webb Space Telescope, named after a former NASA administrator who oversaw the formative years of the Apollo program, is 25 years and $10 billion in the making. It is three times the size of the Hubble Space Telescope and designed to see further into the past than its celebrated predecessor in order to study the first stars and galaxies to turn on in the dawn of time.

The launch on an Ariane rocket on the morning of Dec. 25 was flawless; so flawless that the engineers said it saved enough maneuvering fuel to significantly extend the mission’s estimated 10-year lifetime. But the telescope must complete a monthlong journey to a spot a million miles up, far beyond the moon’s orbit, called L2, where gravitational fields of the Earth and sun commingle to produce the conditions for a stable orbit around the sun.

With a primary mirror 21 feet across, the Webb was too big to fit in a rocket, and so the mirror was made in segments, 18 gold-plated hexagons folded together, that would have to pop into position once the telescope was in space.

Another challenge was that the telescope’s instruments had to be sensitive to infrared or “heat radiation,” a form of electromagnetic radiation invisible to the human eye. Because of the expansion of the universe, the most distant and earliest galaxies are flying away from us so fast that visible light from those galaxies shifts into the longer infrared wavelengths. As a result, the Webb will view the universe in colors no human eye has ever seen.

But in order to detect infrared radiation from distant sources, the telescope has to be very cold, only a few degrees above zero, so that the telescope itself does not interfere with the work.

After years of deployment tests on Earth, small surprises in space have popped up during the Webb’s deployment, or the “getting-to-know-you phase of the telescope,” Bill Ochs, an engineer at the Goddard Space Flight Center and a project manager for the telescope, told reporters on Monday.

Mission managers detected high temperatures on an onboard motor used only in the deployment process, so engineers repointed the telescope on Sunday to protect the device from the sun’s heat. Then the Webb’s solar arrays were readjusted when engineers noticed the telescope had smaller power reserves than expected.

One of the most dicey moments came on Tuesday, with the successful unfolding of a giant sunscreen, the size of tennis court. It was designed to keep the telescope in the dark and cold enough so that its own heat wouldn’t obscure the heat detected from distant stars. The screen is made of five layers of a plastic called Kapton, which is similar to Mylar and just as flimsy, and which had occasionally ripped during rehearsals of its deployment.

In fact, the unfolding went flawlessly this time.

“It went incredibly smoothly. I feel like we’ve all kind of been shocked that there’s been no drama,” said Hillary Stock, a sunshield deployment specialist at Northrop Grumman, the telescope’s primary contractor.

Then on Thursday, the telescope unfurled its secondary mirror, which points at the 18 hexagons, reflecting what the telescope saw back to its sensors.

“We’re about 600,000 miles from Earth, and we actually have a telescope,” Mr. Ochs said on Thursday in the mission operations control room at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

As the telescope ticked off one chore after another, the astronomers who had been waiting 25 years for this telescope began to relax.

“Strangely I don’t feel so anxious anymore, my inherent optimism (hello optimism bias & anchoring bias) is in full gear,” Priyamvada Natarajan, a cosmologist from Yale, wrote in an email.

Two days later the last mirrors locked in place, and the team at mission control broke into applause and a flurry of high fives and fist bumps.

“How does it feel to make history everybody?” Dr. Zurbuchen asked the mission’s managers in Baltimore after the latching was complete. “You just did it.”

“NASA is a place where the impossible becomes possible,” said Bill Nelson, the former senator and astronaut who is now NASA’s administrator.

Garth Illingworth of the University of California, Santa Cruz, said: “I cannot describe how incredible this feels to have a full mirror. It is an astonishing achievement for the J.W.S.T. Team.”

“NASA and the U.S. can still do great things,” Michael Turner, a veteran cosmologist at the Kavli Foundation in Los Angeles, wrote in an email. “I can’t wait for first light and then first science. It will be even better for our COVID-riddled spirits than Ted Lasso.”

Chanda Prescod Weinstein, an astrophysicist at the University of New Hampshire, wrote in an email, “This is such a reminder of how successful people can be when they work together.” She added “I am absolutely thrilled for the team and genuinely excited for what we are going to learn about the cosmos.”

While the telescope is considered fully deployed, much remains to be completed before it performs any astronomical observations. Its primary mirror segments are not aligned enough to produce a coherent image, part of a process that will take about five months.

“But for sure, light can, in principle, now go through J.W.S.T. from objects in the universe and into Webb’s instruments — albeit as 18 very fuzzy blobs, at best, until it is all tuned up!” said Dr. Illingworth, an astronomer.

By the end of January, the telescope will be in its final orbit at L2. The astronomers will spend the next five months tweaking the mirrors to bring them into common focus and beginning to test and calibrate their instruments.

Then real science will begin. Astronomers have said the first picture from the Webb telescope will appear in June, but of what nobody will say.

“I don’t know what the targets will be,” said Antonella Nota, associate director of the European Space Agency, during the NASA webcast on Saturday. “But I know one thing, that they will be absolutely spectacular.”