The magazine’s Ethicist columnist on what you owe to a sibling who didn’t treat you right and how to handle a potential bullying situation at your child’s school.

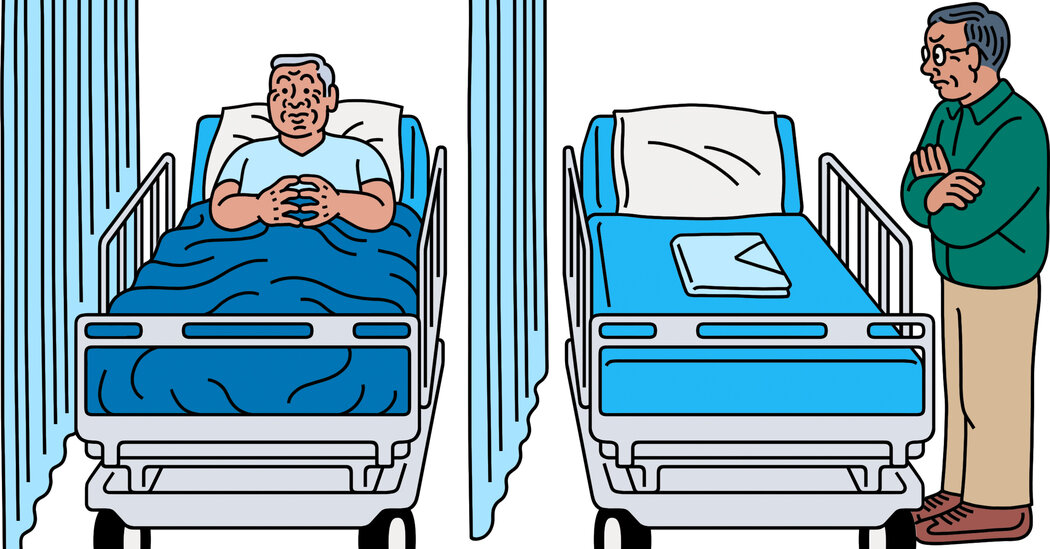

My only sibling, an older brother, is facing kidney issues and may need a donor. I dread receiving a call asking me to fill that role.

When we were quite young, he regularly beat me up, switching to emotional bullying when I was about 11. My parents never thought to intervene. As we got older, distance helped us eventually get along. But in our 50s, when I announced I was marrying, he bullied our mom into rewriting her will to ensure, should I predecease him, that my future stepson would not inherit any of the estate: He would get it all. When settling the estate some years later, he went after more than was justified and showed a marked lack of trust in me. I really don’t think any of his behavior was intentionally malicious — just what he felt he deserved or needed for his own safety. At that point I had enough and stopped interacting with him, except for birthday cards. I’ve politely laid out my feelings in a letter; he eventually acknowledged he may have made “some errors.” But that’s about it.

What’s my ethical responsibility? If it were one of my close cousins needing a kidney, I would most likely be fine with it. But for someone who has never been able to provide, undoubtedly because of his own childhood trauma(s), a “normal” brotherly relationship, I think this would raise old feelings of being his victim. Name Withheld

Every year, thousands of people in our country donate a kidney, and we rightly honor them for that act of generosity. The procedure itself involves some discomfort (a small percentage of people will have long-term pain in the affected region), and it typically takes a few weeks to recover fully. There’s some evidence that donors have an elevated, albeit still low, lifetime risk of kidney failure. Still, the overall medical risks to donors are small, while the benefits to the recipients are typically huge — their lives can be extended by many years. Because of your genetic proximity to your brother, there’s a good chance that your tissues will be well matched, and a well-matched donation will significantly increase the chance of long-term success.

In the light of these facts, some people will see an easy choice here. For them, the key fact is that, if you prove to be histocompatible, your brother can have a longer, better life at little cost to you. Given that you two are brothers, in fact, they may believe that you have even more reason to do it; they may say it rises to the level of a duty.

Oddly, though, utilitarians, who think that morality is a matter of maximizing the good consequences of your acts, are unlikely to agree — because you could probably increase the good done in donating your kidney by looking for a recipient who’s younger than your brother. (And maybe someone who’s nicer, too — extending the life of nicer people contributes not just to their welfare but to the welfare of those they interact with.)

The question isn’t so much what you owe to your brother as what you owe to yourself.

You wouldn’t have written, however, if you thought that all you needed to do was to measure the consequences of this donation. You’re troubled because your brother is . . . well, he’s your brother. And you think — rightly, in my view — that this relationship is relevant to what you should do. Morality doesn’t just permit you to give special consideration to the needs of those with whom you have certain relationships; it requires that you do so. Most people would agree that your brother has a special claim on you. To be sure, kidney donation is not ordinarily a duty. Even if you were on the warmest of terms with your brother, that fraternal claim wouldn’t mean you had a duty to give him your kidney. The donation would still be an act of “supererogation,” something above and beyond what was required.

If being on warm terms doesn’t convert this fraternal claim into a duty, the question arises of how to weight this special claim if you’re on lousy terms. When a responsibility arises from our relationships, does it derive from the fact that we value them? That condition doesn’t hold here: You don’t much value the relationship. Some have argued that we have obligations to our kin simply because they are our kin. But then is it the bare fact of biological relatedness that matters, or is it the fact of being connected through family relationships, so that the duties extend to adopted members of our family? And, if the latter, do we have no obligations to biological kin who were adopted into other families? It’s easy to get lost in this thicket of issues.

In your case, I find myself moved by two thoughts. One is that you’re not the selfish type — you would probably be willing to donate a kidney for a close cousin. Your reluctance here arises from the fact that your brother has been a jerk to you over the years. And whatever your duties are to your brother, there is something ethically troublesome about refusing to help him because it would, as you put it, “raise old feelings of being his victim.” Let’s grant that he has treated you very badly and never apologized adequately for doing so. You have been, in that sense, his victim. But why shouldn’t an act of generosity to someone who has mistreated you make you feel magnanimous instead?

The question isn’t so much what you owe to your brother as what you owe to yourself. Choosing to deny him a life-extending opportunity because he has been rotten to you would be understandable. It would also be ungenerous enough that you shouldn’t want to be the kind of person who would do it.

I am the father of an eighth grader in a suburban New Jersey middle school. Tonight he told me about Paul (not his real name), a boy in his class who eats lunch alone every day in the cafeteria. My son says he remembers Paul as having friends in elementary school, but now he is seemingly friendless, and he is perceived as “weird.”

My son said he recently witnessed a couple of incidents in which Paul was bullied by other students, both boys and girls, in gym class and during lunch hour, bordering on the physical. I asked my son if he would consider befriending Paul. He said no, as he also perceives Paul as somewhat weird and is not interested in being friends. He is also worried about his own standing in the school social structure. (My son is a nonjock, average student who leans toward the arts.)

It’s possible my child may have misperceived the situation, but I am inclined to send the parents a letter, anonymously, to let them know what my son shared. I asked my son if he is OK with this approach, and he said yes, as long as he is not outed as the “snitch.” I do not know the parents, but via the internet I discovered that they appear to be an affluent, civically involved family. Is my idea of sending an anonymous letter to alert them to the possibility that their son might be a victim of bullying the right thing to do? I feel compelled to inform them of what could potentially be a dangerous situation for their son. However, I can’t help feel I’m copping out by dropping this potential bombshell on their plate and saying, “Good luck.” But if I were unaware of my son possibly being bullied, I would want to receive such a letter. Name Withheld

Although you could send that unsigned letter to these parents, why not alert school administrators (and perhaps a guidance counselor) to this situation? If your son is still worried about being identified as the informant, you could alert them anonymously. An educator from your state tells me that even an anonymous note about bullying will trigger an investigation. Responsible school officials know how harmful bullying can be. They’re also in a position to keep an eye out and prevent this misconduct from continuing.

Your son is a decent kid, with a good-hearted father. I just hope you didn’t feel disappointed in him for declining your request. Friendship and affection simply aren’t the kinds of goods you can redistribute. If you were feeling generous, you could give your money to the poor; you cannot give your friends to the friendless. I doubt you could force yourself to enjoy some random person’s company, and you can’t ask this of your son. The fact that he’s concerned about a classmate’s plight doesn’t mean it’s up to him to be his savior.

To submit a query: Send an email to ethicist@nytimes.com; or send mail to The Ethicist, The New York Times Magazine, 620 Eighth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10018. (Include a daytime phone number.) Kwame Anthony Appiah teaches philosophy at N.Y.U. His books include “Cosmopolitanism,” “The Honor Code” and “The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity.”