TV reporters, responding to footage of a West Virginia journalist being hit by an S.U.V., said stations should be more careful about sending reporters out alone.

A video that circulated widely online of a TV reporter in West Virginia being hit by a car during a live broadcast was met with outrage by broadcast journalists who said it underscored the risks of sending reporters to cover stories on their own.

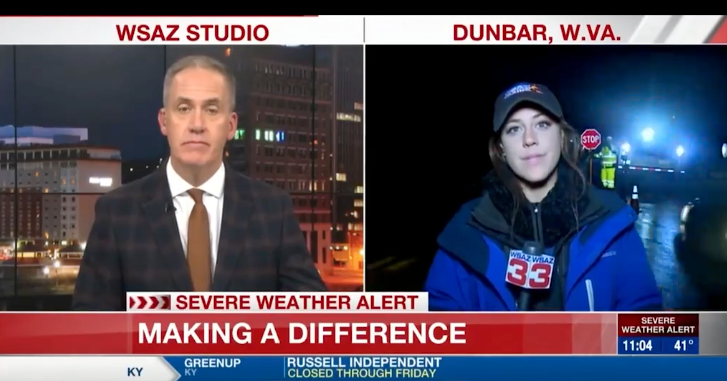

Tori Yorgey of WSAZ-TV in Charleston, W.Va., was reporting on a water main break in nearby Dunbar during the 11 p.m. broadcast on Wednesday when she was struck by a white S.U.V. and knocked down. The camera fell to the ground, and from outside the shot, Ms. Yorgey, 25, could be heard saying, “I just got hit by a car, but I’m OK.”

She got up, adjusted the camera and continued, in what appeared to be good spirits. “You know, it’s my last week on the job, and I think this would happen specifically to me, Tim,” she said, addressing the newscast’s anchor, Tim Irr.

It was not clear whether the station had sent someone to report with Ms. Yorgey, who described moving the camera herself in an exchange with Mr. Irr. “I thought I was in a safe spot, but clearly we might need to move the camera over a bit, so let me do that,” she said.

Her resilience was celebrated in some circles, but the segment hit a nerve with TV reporters, particularly those who are thrust into situations where they are expected to cover stories without a camera operator or producer by their side — a practice known in the industry as using a “one-man band.” Such assignments are often performed by multimedia journalists, or MMJs, who are responsible for setting up the camera, then stepping in front of it to deliver a report.

“She was a good sport about it, but she should not have been put in this situation,” said Ashley Thompson, 35, who worked as a multimedia journalist in Montgomery, Ala., before moving to jobs at television stations in Phoenix and Atlanta. In April 2020, a reporter at her station was carjacked after finishing a live shot in downtown Atlanta. The reporter had been working with a photojournalist who traveled in a separate car.

Ms. Thompson, who no longer works in journalism, said the video was the only thing people who have worked in broadcast news were talking about on Thursday. “As horrified as the industry is, I doubt anything will change, because local news is all about saving money,” she said.

The practice of sending reporters out as a “one-man band” is not new, but it is more widespread today, said C.A. Tuggle, a distinguished professor of journalism at the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“I would really like to see the industry cut back on the number of one-man-band-type of live shots because it is hard to be situationally aware, but I just don’t know whether it would have made a difference in this case,” he said.

Professor Tuggle, who did “one-man band” shots in the 1980s, said that if someone had been with Ms. Yorgey, she still could have been hit by the car because it came from outside the shot.

Whoever assigned the story could have decided the water main break was not a significant enough story to warrant sending out a young reporter on her own late at night, he said. The newsroom could also have provided a reflective jacket or told her to stand farther from the road than she might have thought necessary, he said.

Representatives for WSAZ and the company that owns the station, Gray Television Broadcasting, did not respond to requests for comment on Thursday. Ms. Yorgey, who is starting a job at WTAE-TV in Pittsburgh next month, also did not respond to interview requests.

The controversy was all too familiar to Alanna Autler, 31, who worked as a multimedia journalist for another news station in Charleston years ago. Ms. Autler said she would sometimes enlist help from friends, colleagues and even strangers to feel more secure as she reported from the scene of a crime or natural disaster.

Ms. Autler said managers had on occasion acknowledged that she was being sent to an unsafe location, but there was no one else around to go with or instead of her. “If you’re the lead story, or the only story, because you are the only reporter, then you feel pressure that the entire newscast falls because of you,” she said.

Once, after being asked to cover a rape for an 11 p.m. broadcast, Ms. Autler told her managers she was scared to go by herself, but they did not provide support. She asked her cousin’s boyfriend to ride with her in the news van.

“Station managers and these ownership groups that own local television stations have all of the power, and a lot of these reporters are young, out of college, this is the first job they have, they have no power to voice their concerns,” said Ms. Autler, who left broadcast journalism last year and is now in law school.