Before five men stand trial in March, prosecutors and defense lawyers are examining more than 1,000 hours of secretly recorded conversations.

On a rainy night in northern Michigan in September 2020, a group of armed men divided among three cars surveyed the landscape around the vacation cottage of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, considering how to kidnap her as payback for her Covid-19 lockdown measures.

Two men descended from the lead car to inspect a bridge on Route 31 in nearby Elk Rapids, assessing what was needed to blow it up to delay any police response to the house on nearby Birch Lake.

Later, after team members returned to the rural camp where they had already conducted military-style training exercises, a man identified as “Big Dan” in government documents asked the assembled group, “Everybody down with what’s going on?” Another man responded, “If you are not down with the thought of kidnapping, don’t sit here.”

Of the dozen men on that nighttime surveillance mission, four of them including “Big Dan” were either government informants or undercover F.B.I. agents, according to court documents.

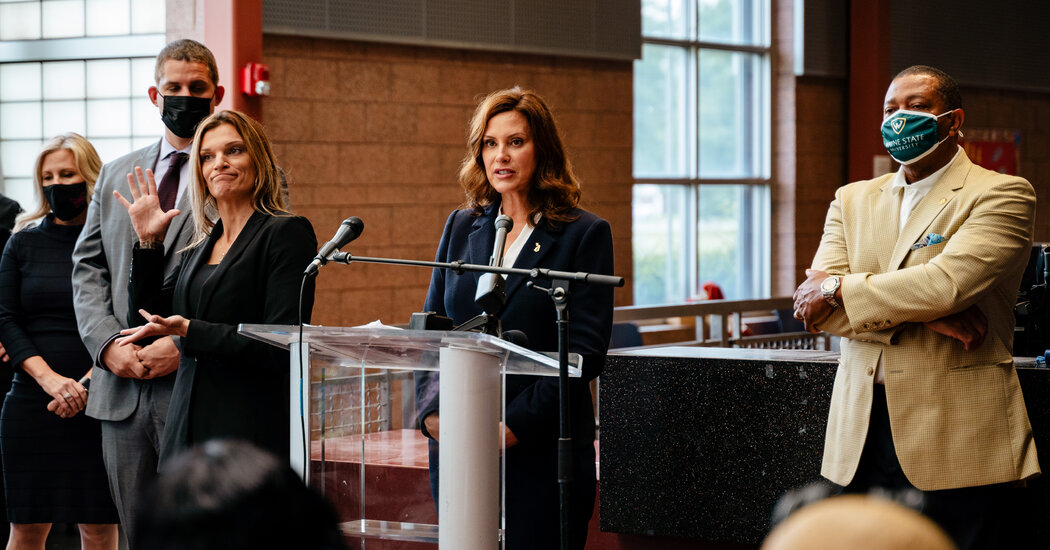

The events of that night will be a key element when, on March 8, five men charged with plotting to abduct the Democratic governor from her vacation cottage will go on trial in U.S. District Court in Grand Rapids, Mich.

The trial is being closely watched as one of the most significant recent domestic terrorism cases, a test of Washington’s commitment in the wake of the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol to pursue far-right groups who seek to kindle a violent, anti-government insurgency or even a new civil war.

The effort to prosecute the kidnapping plot is sprawling. Both the prosecution and the defense are relying heavily on more than 1,000 hours of conversations and other events secretly recorded by informants or undercover agents. The defense lawyers want the case thrown out on entrapment grounds, accusing investigators of “egregious overreaching” by manipulating the accused men to drive the plot forward. Prosecutors will attempt to prove that the suspects were inclined toward the violence from the start.

In another challenge for the case, prosecutors have made an unusual decision not to call to the witness stand three F.B.I. agents with high-profile roles in the investigation. One agent was fired last summer after being charged with domestic violence. Another agent, while supervising “Big Dan,” tried to build a private security consulting firm based in part on some of his work for the F.B.I.

All 14 suspects arrested in October 2020 were members of the Wolverine Watchmen or other armed, paramilitary groups. One of the six facing a federal kidnapping conspiracy charge pleaded guilty and is expected to testify against the rest. The other eight, who participated in some military-style training, were accused in two separate, ongoing state cases on a lesser charge of providing material support for terrorism.

In recent weeks, the already complicated case has become more entangled, with the two sides arguing over what evidence can be presented in federal court.

The informant known as “Big Dan” or “Confidential Human Source-2” in government papers will be the star witness for the prosecution. Descriptions of Dan’s interactions with the suspects are rife throughout the court documents, and he already testified extensively in one state case last year.

Around March 2020, Dan, a veteran in his mid-30s who was wounded in the Iraq war, was working at the post office, looking online for ways to practice his military skills, according to the court documents, when the Wolverine Watchmen’s Facebook page popped up. Members were adherents of the so-called boogaloo movement who seek to speed a societal collapse.

Alarmed by their discussions about targeting law enforcement officers, Dan reported them to local police and eventually agreed to become an F.B.I. informant, he said in state court. He was paid about $54,000 over the course of the roughly six-month investigation.

He was not alone. The F.B.I. deployed at least 12 informants, as well as several undercover agents, according to defense filings. On the nighttime surveillance operation of the governor’s cottage, for example, the defense described “Big Dan” as the main organizer. Stephen Robeson, with a long history of both past crimes and work as an informant, was there too. The “explosives expert” who could topple the bridge was actually an undercover F.B.I. agent, as was a man in another vehicle.

The defense lawyers using that same trove of evidence material have built an entirely different scenario of what happened. They depict the accused as reluctant puppets entrapped by the F.B.I. agents and informants whom they say came up with the kidnapping plot.

Within weeks of joining, Dan took over the training exercises, introducing a much higher level of military tactics, defense lawyers said. They describe him as consulting closely with his main handler, Agent Jayson Chambers, on matters like who should participate in two surveillance trips to Ms. Whitmer’s cottage.

The suspects discussing violence on the recordings or in encrypted chats was just inflammatory rhetoric, the defense says. Prosecutors say Adam Fox, 38, the group’s ringleader, was living in the basement of a friend’s vacuum cleaner shop where he worked, talking about assaulting the Michigan statehouse just as “Big Dan” was getting involved.

The defense lawyers in the federal case either declined or ignored requests to comment, while a spokesman for the U.S. attorney in Western Michigan said the office would not discuss pending criminal matters. The F.BI referred questions to the U.S. attorney.

Sting operations using informants are a thorny tactic in terror cases. In those developed after the 9/11 attacks, F.B.I. agents often got involved when someone expressed interest in joining Al Qaeda or in fomenting some kind of terrorist act. If the suspects had trouble agreeing on a plot or acquiring weapons, the informants or undercover agents would sometimes help them as a way of gauging criminal intent.

Critics of such F.B.I. methods like Michael German, a former undercover F.B.I. agent, accuse the agency of acting like Cecil B. DeMille, manufacturing complicated, theatrical scenarios rather than pursuing the more complex task of unearthing actual extremist plots.

Mr. German, who is now a fellow at the Liberty & National Security Program of the Brennan Center for Justice, said, “Rather than focus on those crimes and investigating them, there appears to be more interest in this method of manufacturing plots for the FBI to solve.”

Prosecutors argue that they remove real threats. Nils R. Kessler, the assistant U.S. attorney prosecuting the kidnapping suspects, has drawn parallels between their plans and the Jan. 6 attack. “As the Capitol riots demonstrated, an inchoate conspiracy can turn into a grave substantive offense on short notice,” he wrote.

Still, prosecutors have sought to distance themselves from Mr. Robeson, 58, another pivotal F.B.I. informant. A paving contractor from Wisconsin and the leader of a paramilitary group, he pleaded guilty in October to federal charges of possessing a high-powered sniper rifle, illegal for a felon. His list of felonies and other crimes dating back to the 1980s included forgery, jumping bail and battery.

Mr. Robeson organized a meeting in Dublin, Ohio, in June 2020 involving members of armed paramilitary groups from half a dozen states as far away as Virginia and Missouri. He also hosted a field training exercise in Wisconsin in July and helped to survey the governor’s cottage. He received nearly $20,000.

In an extraordinary filing in early January seeking to bar recorded statements by Mr. Robeson from the trial, prosecutors called him a “double agent” who had worked “against the interests of the government.” He attempted to get evidence destroyed and offered the defendants funds from a charity to buy weapons, among other acts, they said.

His lawyer, Joseph Bugni, declined to comment.

The entrapment defense has not been uncommon in terrorism cases after 9/11, but is one that juries have not embraced.

“It is a really hard defense. You are saying my client did it, but you should not punish him anyway because it wasn’t fair, somebody manipulated him into it,” said Jesse J. Norris, an associate professor of criminal justice at the State University of New York at Fredonia.

Federal law on entrapment boils down to two issues: whether the suspect was induced to commit the crime, and to what extent he was predisposed toward it. The latter is a gray area, because prosecutors can use almost any conversation referencing violence as proof, legal experts said. The three defendants in one state case are also seeking to have it dismissed on entrapment grounds.

Defense attorneys in the federal case say in court papers that it was Mr. Robeson, an informant, who broached the kidnapping idea at the Ohio meeting, where four of the 15 militia representatives were informants.

The prosecution holds that two of the men charged, Mr. Fox and Barry Croft, first proposed the idea. In denying Mr. Croft bail, a judge quoted him from a recording made at the Ohio meeting. In a conversation that included threats of hurting people, Mr. Croft said, “I’m going to do some of the most nasty, disgusting things that you have ever read about in the history of your life.”

Mr. Croft is among several of the accused who also face federal weapons charges for exploding a homemade bomb.

When the trial begins, the prosecution will have to build its case without some of the F.B.I. agents who were central to the investigation.

After the suspects were arrested, Agent Robert J. Trask II was the main government witness, taking the stand during the first court hearings to describe the entire scenario.

The F.B.I. fired him in July after he was arrested and charged with beating his wife during an argument over an orgy that the two had attended at a hotel in Kalamazoo, Mich. In pleading no contest last December, Mr. Trask said he could not remember that night.

Two other F.B.I. agents have prompted objections from defense attorneys.

Defense attorneys accused Mr. Chambers of trying to leverage his role in the case to help build a private security consulting firm that he eventually disbanded in October 2021. As evidence of the significance of his role, they noted that Mr. Chambers wrote 227 reports about his exchanges with “Big Dan.” Prosecutors said the defendants failed to prove that Mr. Chambers had a financial stake in the case’s outcome.

Defense lawyers in both the federal and state cases have raised questions in court about Henrik Impola, Dan’s other handler, who has testified in court in the investigation. A lawyer in a separate federal case had complained to the F.B.I. that Mr. Impola had committed perjury, they said. Federal prosecutors in the Whitmer case called the accusation “unfounded,” noting that the court in that case made no finding of misconduct against Mr. Impola.

Nonetheless, the government announced in court papers last month that it would not be calling any of the three men to testify, and sought to bar mention of the incidents, saying that they “carry a high risk of unfair prejudice, confusion and misleading the jury.” It has endeavored to downplay the significance of the three men, noting that dozens of agents worked on the investigation.

Even if it is impossible to fully assess a case before the trial reveals all the facts, said Mr. German, the former undercover F.B.I. agent, the revelations thus far have encumbered the prosecution’s task. “There is certainly a lot of lumber that this case seems to have given defense attorneys to build a story about what happened,” he said.

Kitty Bennett contributed research.