“Report From Engine Co. 82” was the first of his 16 books. He also started Firehouse magazine and was the founding chairman of the New York City Fire Museum.

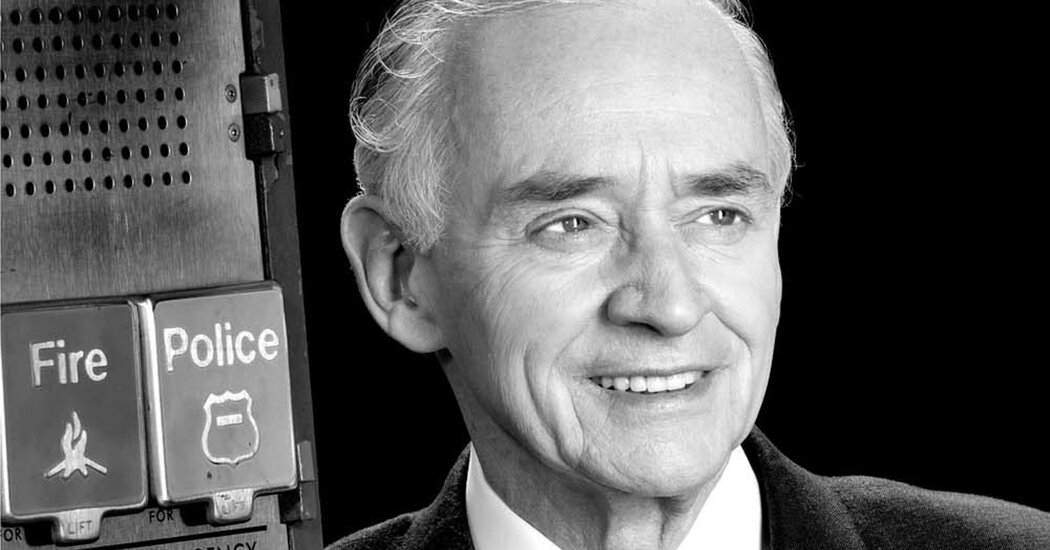

Dennis Smith, a former teenage hellion and high school dropout who transformed himself into a famed New York City firefighter, a gritty best-selling author and a leading guardian of the safety of his colleagues and the public, died on Friday in Venice, Fla. He was 81.

His death, in a hospital, was caused by complications of Covid-19, his son Sean Smith said.

Mr. Smith was headed for jail as a juvenile delinquent when a sympathetic judge offered him an alternative: Join the military. He enlisted in the Air Force, returned to New York three years later and joined the Fire Department.

While earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees at night, his literary career began when a magazine editor read an erudite letter by Mr. Smith published in The New York Times Book Review disputing the author Joyce Carol Oates’s characterization of William Butler Yeats as a universal poet rather than primarily an Irish one. The editor was stunned to discover the letter was signed by a Dennis E. Smith, who identified himself not as a literary critic or public intellectual but as a Bronx fireman.

The editor’s intervention helped lead to a contract for the first of 16 books, “Report From Engine Co. 82” (1972), a chronicle of the city’s busiest firehouse. The book sold some three million copies, ennobled Mr. Smith as a champion of his profession and inspired countless men and women to become firefighters.

“The author’s pride clearly derives not from his writing, but from his job as a firefighter — the most hazardous job of all, according to the National Safety Council,” Anatole Broyard wrote in his Times book review. “The risk one takes in writing a book — and there are those who will tell you that this is the most hazardous occupation — must seem comparatively small to him. One hopes he will go on taking it.”

He did. His “Report From Ground Zero: The Story of the Rescue Efforts at the World Trade Center” (2002) was No. 2 on The Times’s best-seller list.

Mr. Smith was a Renaissance firefighter.

He played eight musical instruments; founded Firehouse magazine in 1976 (and sold it in 1991, making $7 million); was the founding chairman of the New York City Fire Museum and was instrumental in converting the Engine Company 30 firehouse in SoHo as its site; was president and chairman of the Kips Bay Boys and Girls Club, which moved from Manhattan to the South Bronx; and was a chairman of the New York Academy of Art.

Mr. Smith was the first chairman of the International Association of Fire Chiefs’ Near Miss task force, focused on preventing firefighter injuries and deaths, and won awards from the Congressional Fire Services Institute, the National Fire Academy and the New York Fire Department.

Dennis Edward Smith was born on Sept. 9, 1940, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. He was raised in the East 50s of Manhattan when it was an Irish and Italian neighborhood that inspired Sidney Kingsley’s play “Dead End.”

His father, John, a Scottish immigrant, was committed to an asylum when Dennis was 2. His mother, Mary (Hogan) Smith, was a telephone operator and took in laundry and cleaned apartments on nearby Sutton Place to support her two sons when the family went on welfare.

His mother was a disciplinarian who instilled in Dennis a love of books. He attended parochial schools, where, as a profile in The Times put it, “when you were poor and Irish and growing up on the East Side in the 1950s, the nuns never told you to become a doctor or a lawyer — President of the United States perhaps, but if not that, then a policeman or a fireman.”

He wrote about his childhood in “A Song for Mary: An Irish-American Memory” (1999).

He quit Cardinal Hayes High School in the Bronx at 15 during his first year; he delivered flowers but also went joy riding in stolen cars and bought heroin in Harlem. After being arrested during a brawl in Queens, he was saved from himself by the sentencing judge and an earnest boys’ club counselor.

Mr. Smith served as an Air Force radar operator in Nevada, returned and joined the Fire Department in 1963. He was assigned to a Queens firehouse and in 1966 transferred to the Engine Company 82 in Morrisania when the Bronx was burning. He later moved with his family to suburban Orange County, N.Y.

Deciding that he might eventually teach at a community college, he earned a bachelor’s degree in English from New York University in 1970 and a master’s in communications from N.Y.U. two years later. While he was still a part-time student, working full-time as a firefighter, he wrote the letter to The Times Book Review challenging Ms. Oates’s definition of Yeats as a universal poet.

“Please remember,” Mr. Smith wrote, “that the poet, as evidenced by his writings, was Irish first.”

Through circuitous routes, he was contacted by an editor at McCall’s magazine, was featured in a New Yorker interview, was commissioned to write an article for True magazine for $1,500 and received a $30,000 advance for his proposed book on Engine Company 82.

His marriage to Patricia Kearney in 1962 ended in divorce in 1985. In addition to their son Sean, he is survived by two other sons, Brendan and Dennis; two daughters, Deirdre Smith-Wisniewski and Aislinn Falzarano; and 11 grandchildren.

He remained with the department until 1981, returning as a volunteer after the World Trade Center attack in 2001 where he worked for months on the cleanup. He helped retrieve the body of the son of a fellow firefighter, Lee Ielpi, that December. He later developed cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which his family attributed to dust inhaled at the site.

In a Times opinion essay in 1971, Mr. Smith recalled his ebullience at the prospect of becoming a firefighter: “I would play to the cheers of excited hordes — climbing ladders, pulling hose, and saving children from the waltz of the hot masked devil. I paused and fed the fires of my ego — tearful mothers would kiss me, editorial writers would extol me in lofty phrases, and mayors would pin ribbons to my breast.”

After eight years, he wrote, the romantic visions had faded.

“I have climbed a thousand ladders, and crawled Indian fashion down as many halls into a deadly nightshade of smoke, a whirling darkness of black poison, knowing all the while that the ceiling may fall, or the floor collapse, or a hidden explosive ignite,” Mr. Smith added. “I have watched friends die, and I have carried death in my hands. With good reason have Christians chosen fire as the metaphor of hell.”

“There is no excitement, no romance, in being this close to death,” he wrote, later adding: “Yet, I know that I could not do anything else with such a great sense of accomplishment.”

He recalled a tenement fire in which an 18-month-old girl died. The teary would-be rescuer, a fellow firefighter, sat by him on the stoop, holding the body and saying over and over, “Poor little thing, she never had a chance.”

To which Mr. Smith wrote: “I wish now that each man who intends to file for the coming fireman’s test could have seen the humanity, the sympathy, and the sadness of those eyes, for they explained why we fight fires.”