The vast collection of artifacts at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., includes dozens of items from the careers of Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens. There are bats and helmets used by Bonds, spikes and caps used by Clemens, and much more. Those players are essential to the history of baseball, and the hallowed museum tells their stories.

The plaque gallery does not, because neither Bonds nor Clemens has collected 75 percent of the votes in their first nine appearances on the baseball writers’ ballots. The results of the latest election, the last for Bonds and Clemens, will be announced on Tuesday. It is not looking good for either player.

More than 160 writers — roughly 45 percent of the expected electorate — have publicly revealed their ballots. A Twitter account that compiles the results, run by Ryan Thibodaux, has counted slightly less than 75 percent of ballots for both Bonds and Clemens.

But writers who keep their votes private have been much less likely to vote for either player; last year, Bonds and Clemens just barely cleared the 50 percent mark among that substantial voting bloc. Both players have been stuck between 59 and 62 percent overall in each of the last three elections. That number may be higher this time, but it will likely still be well short of the required 75 percent.

The reason, of course, is that both players — and Sammy Sosa, a curious afterthought among voters — are strongly tied to performance-enhancing drugs. Writers are given these guidelines: “Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.” This is the so-called character clause that has complicated the reckoning of the steroid era and will continue to do so for many years, now that Alex Rodriguez is on the ballot for the first time.

The Hall of Fame has always outsourced the voting to the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, and its board has shown no desire to change that process. (The New York Times does not permit its writers to vote.) Even when candidates fall off the writers’ ballot, they can still be considered by special committees that study various eras of baseball history. Six new Hall of Famers were elected this way in December — Bud Fowler, Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso, Buck O’Neil and Tony Oliva.

But even if the writers elect nobody on Tuesday, there will still be an induction ceremony in Cooperstown this July. These are the trends worth noting when the results are announced on MLB Network at 6 p.m.

David Ortiz and the Pudge Factor

The most likely candidate to be elected this year is David Ortiz, the celebrated Boston slugger, who has been named on nearly 84 percent of public ballots. But Ortiz carries baggage of his own from the steroid era: a positive test in 2003, when baseball conducted survey testing (without penalties) that was supposed to have remained anonymous.

Ortiz made 10 All-Star teams, all after 2003, and never tested positive again. His case could mirror that of Ivan Rodriguez, known to many as Pudge, the 14-time All-Star catcher who was named as a steroid user in Jose Canseco’s book in 2005 and then showed up at spring training looking noticeably slimmer. Those factors deterred some voters, but ultimately weren’t enough to keep Rodriguez out of Cooperstown — he made it in on his first try, in 2017, with 76 percent of ballots.

The Suspension Gap

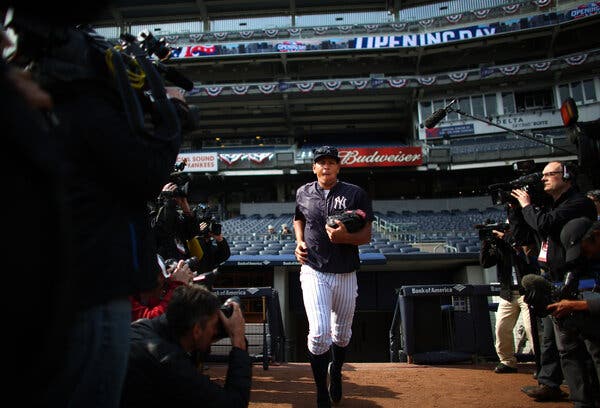

Alex Rodriguez did everything a Hall of Famer could do: 696 homers, 3,115 hits, three Most Valuable Player Awards, Gold Gloves, a batting title, a 40/40 season, a World Series championship. He also served a yearlong suspension for performance-enhancing drugs in 2014, after already admitting to steroid use in the early 2000s.

If you vote for Bonds and Clemens, but not Rodriguez, you’re making a clear distinction between those suspected of cheating before the testing era and those who were suspended during it. We’ve seen this play out, to some degree, with Manny Ramirez, another player with both Hall of Fame credentials and a drug suspension — actually, two — on his record. Ramirez garnered 28.8 percent of votes last year, about 33 percentage points lower than Bonds and Clemens received.

Rodriguez, though, had a better career than Ramirez; he is in that stratosphere, with Bonds and Clemens, among the greatest players ever. The gap between votes for Bonds or Clemens and those for Rodriguez will show just how badly Rodriguez cost himself with the 2014 suspension. This year, he has collected only around 40 percent of public votes.

The Two Curt Schillings

Curt Schilling is the only retired pitcher with 3,000 strikeouts and fewer than 750 walks. He was a postseason standout for three teams, and he won awards named for Roberto Clemente, Lou Gehrig, Fred Hutchinson and Branch Rickey that honored his character and charity work.

Yet Schilling’s social media posts got him fired from ESPN in 2016, the same year he shared a joke about lynching journalists. Even so, he has continued to build momentum among writers, who gave him 71.1 percent of the vote last year — more than any other candidate, but not quite 75 percent.

It is clear now that Schilling will not get the goodwill bump most candidates receive when they come so close. When he narrowly missed election, he blasted the news media in a Facebook post in which he asked the Hall of Fame to remove his name from the ballot, writing: “I’ll defer to the veterans committee and men whose opinions actually matter.”

The Hall denied his request, but many writers have honored it by dropping him from their ballots. Schilling’s share has dipped to around 60 percent, meaning that a different group will have to reconcile the two competing versions of Schilling: the one on the mound and the one on the internet.

The Ascent of Scott Rolen

Of the 422 writers who voted for the 2018 Hall of Fame class, only 43 checked the box for Scott Rolen. It was a loaded ballot, with seven future electees, plus Bonds, Clemens and Schilling. Still, 10.2 percent was a dreary first-ballot showing for Rolen, an eight-time Gold Glove winner at third base, mostly for Philadelphia and St. Louis.

Look at him now. Since that vote, Rolen has appeared on 17.2, 35.3 and 52.9 percent of Hall ballots, and he’s polling at just under 70 percent for 2022. Third base is the least-represented position in the Hall of Fame, with just 17 members, and Rolen’s all-around performance should make him the next person selected at that position. He batted .281 with a .364 on-base percentage and a .490 slugging percentage for his career — very similar to Ron Santo, a five-time Gold Glover who was inducted by an era committee in 2012.

Curiously, Rolen’s longtime Phillies teammate, Bobby Abreu, has received almost no support. Abreu, an outfielder for 18 seasons, reached base more times than Tony Gwynn, Lou Brock, Mike Schmidt and other inner-circle Hall of Famers, yet he has received only about 11 percent of the public votes.

The Men in the Middle

Four players have been polling between 45 and 60 percent: Todd Helton, Andruw Jones, Gary Sheffield and Billy Wagner. Of that group, Helton, the longtime Colorado first baseman, has had the fewest appearances on the ballot (four) and is receiving the most support (about 57 percent). That positions him at the front of this pack.

Jones (fifth ballot) and Wagner (seventh) have compelling positives and negatives. Jones was a defensive marvel but was essentially washed up by age 30. Wagner was a dominant closer but struggled in October and pitched only 903 career innings.

Sheffield (eighth ballot) is probably the best-qualified candidate who has yet to cross 50 percent. A feared slugger who rarely struck out, Sheffield had 509 homers and a .907 on-base plus slugging percentage. Voters have seized on Sheffield’s defense and his rather flimsy tie to performance-enhancing drugs: Sheffield worked out with Bonds one winter and admitted to using a cream on his legs that he did not know was considered a designer steroid.

The Curious Case of Jeff Kent

It’s not that writers are punishing Jeff Kent for his prickly personality; remember, the famously silent Steve Carlton cruised into Cooperstown in 1994. The more likely cause of Kent’s poor showing, it seems, is an overemphasis on wins above replacement.

Kent accumulated 55.5 WAR; among second basemen, that’s right between Joe Gordon, who needed 59 years to reach Cooperstown, and Ian Kinsler. But while Kent added little value on defense, he holds the record for homers by a second baseman, with 351. Overall, he hit .290 with a .356 on-base percentage and a .500 slugging percentage. The only other regular second baseman to exceed all three of those figures is Rogers Hornsby.

The writers gave Kent a Most Valuable Player Award in 2000, but he still hasn’t gotten even one-third of their votes for the Hall. Last year, his eighth on the ballot, Kent managed only 32.4 percent — and he’s polling even lower now.

Mark Buehrle, Tim Hudson, and the Fight for Survival

Though they pitched very recently, Mark Buehrle and Tim Hudson might as well be Pud Galvin and Old Hoss Radbourn. Last season, only four starters in the majors reached 200 innings, a figure Buehrle exceeded for 14 consecutive seasons. He and Hudson both worked more than 3,000 career innings, a threshold only one active pitcher, Zack Greinke, has crossed.

Alas, for Buehrle and Hudson, consistency and durability haven’t counted for much with the voters. Both players are in danger of falling below 5 percent, which would drop them from future writers’ ballots. Buehrle received 11 percent in his debut last year; Hudson just 5.2 percent — and early returns are discouraging.

Whatever happens, their tenuous status is an ominous precedent for another stalwart of the era, Jon Lester, who retired this month. Buehrle, Hudson and Lester all made several All-Star teams but never won a Cy Young Award, earned at least 200 wins while making fewer than 500 starts, and had an E.R.A. between 3.49 and 3.81. Lester’s candidacy will need to rely heavily on his dazzling World Series record.

The Demise of Omar Vizquel

Omar Vizquel holds the record for games played at shortstop, 2,709, and won 11 Gold Gloves at the position. In 2019, his third year on the Hall of Fame ballot, he reached 52.6 percent of the vote.

In December 2020 — after many voters had already cast their ballots — Vizquel’s estranged wife, Blanca, told The Athletic that he had physically abused her on multiple occasions. Vizquel denied the accusations, but his share of the vote dropped to 49.1 percent.

Then came a federal lawsuit filed last August in Birmingham, Ala., in which Vizquel was accused of sexually abusing a batboy with autism in 2019 while managing a team in the Chicago White Sox farm system. The White Sox quietly fired Vizquel shortly after the lawsuit was filed, and last summer he was fired from his position as a manager in the Mexican League.

Vizquel’s case presented a new kind of test for the character clause: not chemically enhanced statistics, not aggressive rhetoric, but allegations of deeply disturbing off-field misconduct. If Vizquel were a stronger candidate, these circumstances would provoke an unavoidable, uncomfortable debate. But because he is not, Vizquel — conveniently — has tumbled down the memory hole and has been dropped from the ballot by dozens of writers, collecting only 11 percent of the publicly available vote.