THE HARD SELL

Crime and Punishment at an Opioid Startup

By Evan Hughes

The pharmaceutical industry is enjoying a very good crisis. The rapid development of safe and effective Covid-19 vaccines and treatments has turned drug companies into much-feted heroes. Chipper executives are boasting about saving billions of lives. Shareholders are swimming in profits.

It is a remarkable turnaround for an industry that had been widely reviled. Prepandemic, pharmaceutical companies were routinely berated for the outrageous prices they charged for drugs developed with taxpayer support. They were hauled before grand juries for their roles in what was, until the onset of Covid-19, the country’s most pressing public health crisis: the opioid epidemic.

Even as it has been overshadowed by the coronavirus, the opioid crisis has grown worse. In the most recent 12-month period for which data are available, more than 100,000 Americans — a record number — died of overdoses. Many were killed by fast-acting synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which is found in illegal street drugs and prescription painkillers.

Anyone who has read “Empire of Pain,” Patrick Radden Keefe’s epic exposé of the Sackler family behind Purdue Pharma, is aware of opioid peddlers’ dirty hands. But until I read “The Hard Sell,” about the outrageous behavior of an obscure drug company, I hadn’t appreciated the full extent of the filth or the dark stain the opioid sector has left on the entire industry.

“The Hard Sell,” by the journalist Evan Hughes, is a fast-paced and maddening account of Insys Therapeutics, whose entire business model seemed to hinge on crookedness. (The book is based in part on a 2018 article Hughes wrote for The New York Times Magazine.) Its sole branded product was Subsys, a fentanyl-based liquid that patients sprayed under their tongues. Insys executives went to extraordinary — and at times criminal — lengths to get their addictive and dangerous drug into as many mouths as possible.

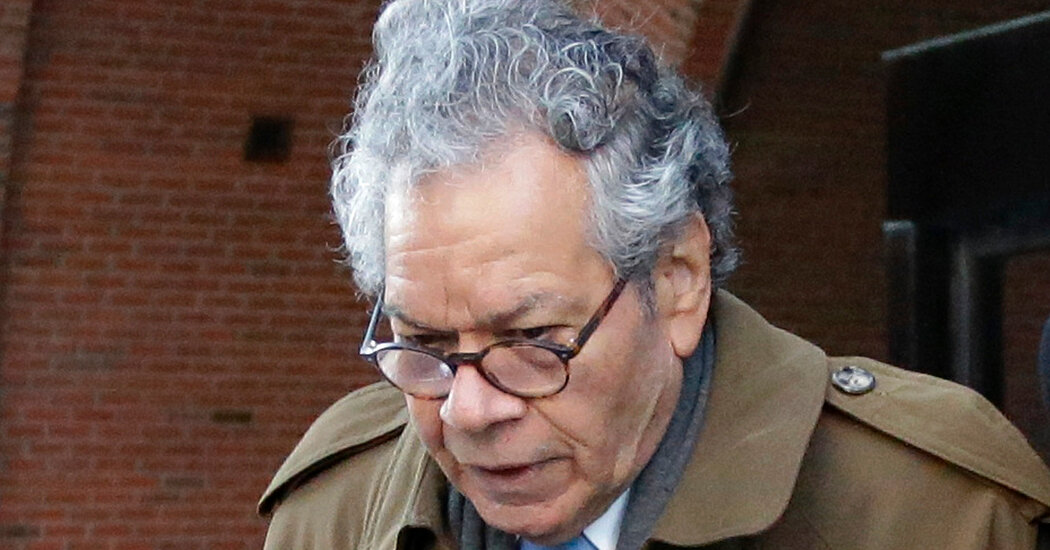

The company was founded in Arizona by “an Indian-born visionary,” John Kapoor. He was a serial drug company entrepreneur who, despite repeated scrapes with regulators, investors and business partners, managed to emerge, over and over, with his fortune and reputation largely intact. (A judge found one of his early companies to have been, as Hughes puts it, “rife with misconduct,” and the Food and Drug Administration reprimanded it for endangering patient health.)

Kapoor was cut from a mold that will be familiar to readers of “Bad Blood” or “The Cult of We” (about the Theranos and WeWork debacles, respectively). He was blindly ambitious, with a sympathetic origin story that disguised his broken moral compass. Whereas Elizabeth Holmes would tell people that she started her pinprick blood-testing company because she feared needles, Kapoor claimed to have come up with the idea for Subsys after watching his wife endure excruciating pain as she died from breast cancer.

Hughes is skeptical about this cover story. The more likely explanation, he suggests, is that Kapoor detected a lucrative opportunity to jump into the booming opioid market with a newfangled narcotic.

The innovation with Subsys was not the drug itself — its active ingredient, fentanyl, has been around since 1960 — but the delivery mechanism. An arms race was underway to develop the fastest-acting opioids. Spraying fentanyl molecules under your tongue turned out to be a super-efficient way — “close to the speed of IV drugs administered in a hospital,” Hughes writes — to deliver pain relief.

Kapoor’s company won F.D.A. approval for Subsys to be used as a treatment for cancer patients. But that was a limited and already crowded market. From the get-go, Insys’ goal was to tap into the much larger pool of people who suffered from a broad range of pain. To do that, Kapoor and his team at Insys borrowed tactics from their rivals and exploited the peculiarities of the pharmaceutical industry.

The company bought access to pharmacy data that showed which doctors were prescribing lots of fast-acting synthetic opioids. About 170 doctors nationwide were responsible for roughly 30 percent of all prescriptions for these drugs, and Insys dispatched its sales force to persuade this tiny group of like-minded physicians to start prescribing Subsys. (Yes, it is crazy that drug companies are permitted to access this sort of easily abusable data.)

Allowing for even more precise targeting of amenable doctors, the F.D.A. required drug companies like Insys to closely monitor who was prescribing their drugs. “The purpose of collecting this data was to protect patient safety, but Insys found itself with a marketing gold mine,” Hughes writes. Soon doctors who prescribed Subsys began finding Insys salesmen in their offices, pushing them to write more scripts.

The Insys sales force initially tried to pitch Subsys on its merits, but there was a problem: Competitors were showering this small band of doctors with free meals, gifts and money. To succeed, Insys needed to play the same game.

Bribery is frowned upon, so, in addition to being plied with food, booze and fun, the doctors were paid to give speeches about Subsys to small audiences — sometimes to the staffs of their own offices. “The idea was to funnel cash to the speaker so that he would prescribe Subsys in return,” Hughes writes. “If he didn’t live up to his end of the deal, he wouldn’t get paid to speak anymore. It was a quid pro quo.”

The entire opioid business seems to have been awash in these underhanded tactics; as Hughes notes, “Nothing that Insys did was truly new.” Indeed, what’s most surprising and powerful about “The Hard Sell” is not one company’s criminality — we’ve grown inured to corporations behaving badly — as much as how institutionalized these practices were across the modern drug industry.

For Insys and its top executives, this was highly profitable. The price of some Subsys prescriptions ran into the tens of thousands of dollars. (When insurance companies began balking at covering these costs, Insys set up a centralized office to secretly file and process paperwork on doctors’ behalf.) Insys went public in 2013 and was the year’s best performing I.P.O., with its shares more than quadrupling.

By then, even as Wall Street and the business media celebrated Insys, the wheels were beginning to come off.

Conscientious insiders warned the government about the company’s fraudulent and abusive practices. Soon federal investigators were closing in. Kapoor and his inner circle would be the rare corporate executives to face criminal prosecution. Hughes recounts the chase and trial in dramatic fashion.

My one big complaint about “The Hard Sell” is that it’s unclear how much damage Subsys did in the context of the broader opioid epidemic. Hughes includes tales of people overdosing and becoming addicted, of lives and families shattered, but I was left unsure whether prescription drugs like Subsys were a root cause of the fentanyl crisis, a contributing factor or a meaningless blip.

At times I wondered if the answer might be the latter and if Hughes was dodging an inconvenient fact so as not to deflate an otherwise compelling story. If so, he needn’t have worried. Even if Insys turns out to be a footnote in the opioid epidemic, there is value in exposing the world to the scummy underbelly of a powerful industry — especially one that has become the sudden object of so much public gratitude.