Biden administration officials told lawmakers that a large-scale Russian invasion could kill as many as 50,000 Ukrainian civilians and prompt a refugee crisis in Europe.

WASHINGTON — Senior Biden administration officials told lawmakers this past week that they believed the Russian military had assembled 70 percent of the forces it would need to mount a full invasion of Ukraine, painting the most ominous picture yet of the options that Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin, has created for himself in recent weeks.

During six hours of closed meetings with House and Senate lawmakers on Thursday, the officials warned that if Mr. Putin chose the most aggressive of his options, he could quickly surround or capture Kyiv, the capital, and remove the country’s democratically elected president, Volodymyr Zelensky. They also warned that the invasion could prompt an enormous refugee crisis on the European continent, sending millions fleeing.

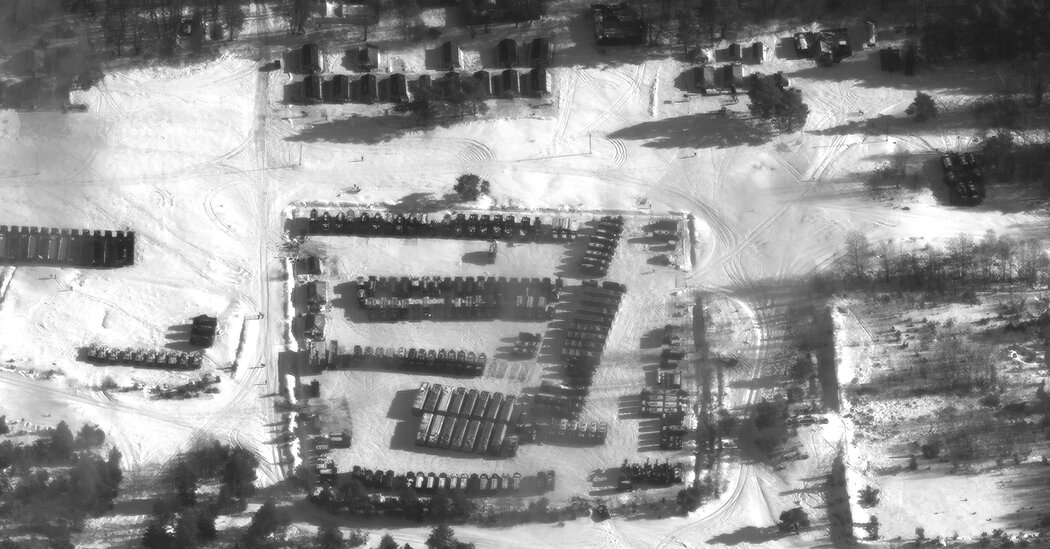

The officials stressed that U.S. intelligence analysts still did not assess that Mr. Putin had made a final decision to invade. But satellite imagery, communications among Russian forces and images of Russian equipment on the move show that he has assembled everything he would need to undertake what the officials said would constitute the largest military operation on land in Europe since 1945.

They also warned of enormous possible human costs if Mr. Putin went ahead with a full invasion, including the potential deaths of 25,000 to 50,000 civilians, 5,000 to 25,000 members of the Ukrainian military and 3,000 to 10,000 members of the Russian military. The invasion, they said, could also result in one million to five million refugees, with many of them pouring into Poland.

Should Mr. Putin decide to invade, American officials believe he is not likely to move until the second half of February. By that point, more ground will have frozen, making it easier to move heavy vehicles and equipment, and the Winter Olympics in Beijing will have ended or be winding down, which could help Mr. Putin avoid antagonizing President Xi Jinping of China, a critical ally for the Russian president.

The grim briefings were the latest salvo in weeks of grave messaging from the Biden administration about Mr. Putin’s plans. On the same day as the briefings, the administration also publicly warned that Russia may try to stage a false-flag operation suggesting that Russian-speaking populations are being attacked, which could create a pretext for an overt military operation. The drumbeat of warnings is part of a concerted campaign by the administration to expose Mr. Putin’s maneuvers in an attempt to build international pressure on him and make clear to him the risks to Russia of escalating the situation further.

Whether Mr. Putin decides to go through with a maximalist approach or a more scaled-down version is the question with which American, European and Ukrainian officials are all grappling.

For example, European officials, examining the same evidence, suggest that Mr. Putin could start smaller and test the reaction — with cyberattacks to paralyze Ukraine’s electric grid and communications, an invasion limited to the Russian-speaking territory in eastern Ukraine or an effort to cut the country in half, roughly along the Dnieper River. American officials have acknowledged the possibility, especially if Mr. Putin wants to see if a smaller military action would create more divisions within Europe over whether to impose the most crushing economic sanctions.

Western intelligence officials also say they have picked up chatter suggesting Russian military leaders are confident they could take Ukraine in a blitzkrieg attack, but worry that they may not be able to hold on to the country, especially if the invasion sets off a significant insurgency. That has prompted speculation inside the NATO alliance that Mr. Putin might invade, seek to change the Ukrainian government and then partly withdraw his forces.

The briefings to Congress on Thursday were led by Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III; Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken; Avril D. Haines, the director of national intelligence; and Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The American officials described to lawmakers five options that Mr. Putin could take, depending on the scope of his ambitions and his calculations about whether he would rather try to take the whole country quickly, no matter the human and economic cost to Russia, or attack it in pieces, in hopes of dividing Europe and NATO allies.

The options include a coup that would depose Mr. Zelensky; a limited incursion into eastern Ukraine similar to what Mr. Putin did when he annexed Crimea in 2014; an incursion into the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine accompanied by a Russian declaration of Donbas as an independent republic; or a Donbas incursion followed by an invasion and annexation of all of the eastern part of the country.

The worst-case assessment is that Mr. Putin is preparing to take the entire country — the scenario that would most likely produce the greatest casualties and, presumably, prompt the harshest sanctions from the United States and Europe.

Mr. Putin, General Milley told lawmakers, is putting in the “military capability to do any and all, building himself a set of options.”

The unclassified parts of the briefings to lawmakers were described to The New York Times by officials in the room, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Diplomats and intelligence officials from three other countries involved in seeking to deter a Russian invasion confirmed the broad outlines of the status of Russian forces, though they disagreed about the importance of certain elements.

After hearing from administration officials, Senator Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, told reporters that a Russian invasion was a “near certainty.” He added that “if we now live in an era where someone can move into a country and just take it over and claim it as their own, I don’t think it’s going to stop at Ukraine,” echoing the fear that Mr. Putin may be trying to redraw the map of the continent to return to the days of the Soviet Union.

Increased planning in Russia’s military apparatus began last fall, Biden administration officials told lawmakers. The expansiveness of the effort alarmed intelligence analysts, who assessed that Mr. Putin had concluded that he would need some 150,000 troops from 110 battalion tactical groups to conquer Ukraine, which the Russian president views as a part of Russia.

The officials said that, as of this past week, Mr. Putin had amassed about 70 percent of the forces he would need to pull off a large-scale invasion to take the entire country, with more than 110,000 troops at the border with Ukraine from 83 battalion tactical groups. Some 14 additional groups were in transit to the border, the officials said.

They said that more Russian troops were heading to the border and that they had been positioned in a manner that suggested a pincer movement, in which Russia would invade the country from three sides. Thirty thousand troops, according to American and NATO estimates, are now in Belarus, which borders Ukraine to the north.

Ballistic missiles in Belarus, and to the east inside Russian territory, have captured British and Ukrainian attention in recent days. The Iskander-M missiles are mounted on mobile launchers, meaning they can be rolled closer to the border in short order, and they have a range of about 300 miles. That suggests that Mr. Putin, if he chose, could begin attacking cities and military emplacements before he moved any troops over the border.

Understand the Escalating Tensions Over Ukraine

A brewing conflict. Antagonism between Ukraine and Russia has been simmering since 2014, when the Russian military crossed into Ukrainian territory, annexing Crimea and whipping up a rebellion in the east. A tenuous cease-fire was reached in 2015, but peace has been elusive.

Mr. Austin and General Milley described to lawmakers a bristling array of additional Russian military assets that have encircled Ukraine. They include 11 amphibious assault ships, in the Black Sea and in the Mediterranean, with the capacity to carry five battalions of Russian Marines who could land in Ukraine from the south, the officials said. In addition, Mr. Putin has deployed a number of submarines to the Black Sea, the defense officials told lawmakers.

Mr. Putin has also deployed Special Operations forces — some 1,500 troops — near and even inside the Ukrainian border, the officials told lawmakers. Those troops, they said, work closely with the Russian military intelligence agency, the G.R.U., which has in the past directed cyber and other attacks on foes.

European officials tend to be more skeptical that Mr. Putin would try to take the country in a large-scale invasion. Some believe that he would seek to take the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, where a grinding proxy war has been underway since 2014.

Another theory is that Mr. Putin could expand that operation in an effort to annex all of eastern Ukraine, up to the Dnieper River. Along the way he could try to decimate Ukrainian troops in that part of the country, roughly half of the Ukrainian military. That could incite panic in the western part of Ukraine — where resistance to Russia might be highest — and prompt people to flee the country. Over time, that could lead top government officials to flee or to try to rule from exile.

American and European officials have made clear that a physical attack over the borders of Ukraine would lead to enormous sanctions on Russia’s banks, trade restrictions on semiconductors and other high-tech items and the freezing of the accounts of Russian oligarchs and leaders. But there is far less unanimity, as President Biden himself has acknowledged, about how to respond to a “minor incursion.” Or even what a minor incursion might be.

European and American officials worry that Mr. Putin might try to stage a coup in Kyiv. Another possibility is a cyberattack devised by Russia that tries to bring down parts or all of Ukraine’s electric and communications infrastructure, similar to the 2015 and 2016 attacks on parts of the country’s electric grid.

European officials say it is unclear how the Western allies would respond to such an attack. If they believed that the cyberoperations were a face-saving way for Mr. Putin to act and then retreat, they note, there might be a temptation to de-escalate and not seek to impose major sanctions, especially if there were few human casualties. On the other hand, a cyberattack could be a prelude to a full invasion, essentially cutting off Ukraine’s ability to communicate or track where Russian forces were coming from.

Michael Schwirtz contributed reporting from Kyiv, Ukraine.