As Covid-19 continues to reverberate throughout the United States, millions of Americans remain catastrophically delinquent on rent.

Fortunately, the federal government has created a roughly $46 billion program for state and local governments to help keep renters in their homes. Called the Emergency Rental Assistance program, it is one of the largest rental assistance efforts in U.S. history.

But the E.R.A. program is fundamentally flawed. The way that the money is generally distributed — a relatively simple formula based on population, rather than each state’s need — could leave hundreds of thousands of renters facing eviction across half the states.

To calculate the amount of money that renters in each state need, we analyzed regional differences in unemployment, poverty and housing costs. We estimate that the average renter household behind on rent owes three months’ worth. Renters’ total arrears are often even larger, as surveys have shown that many renter households have also fallen behind on utility payments.

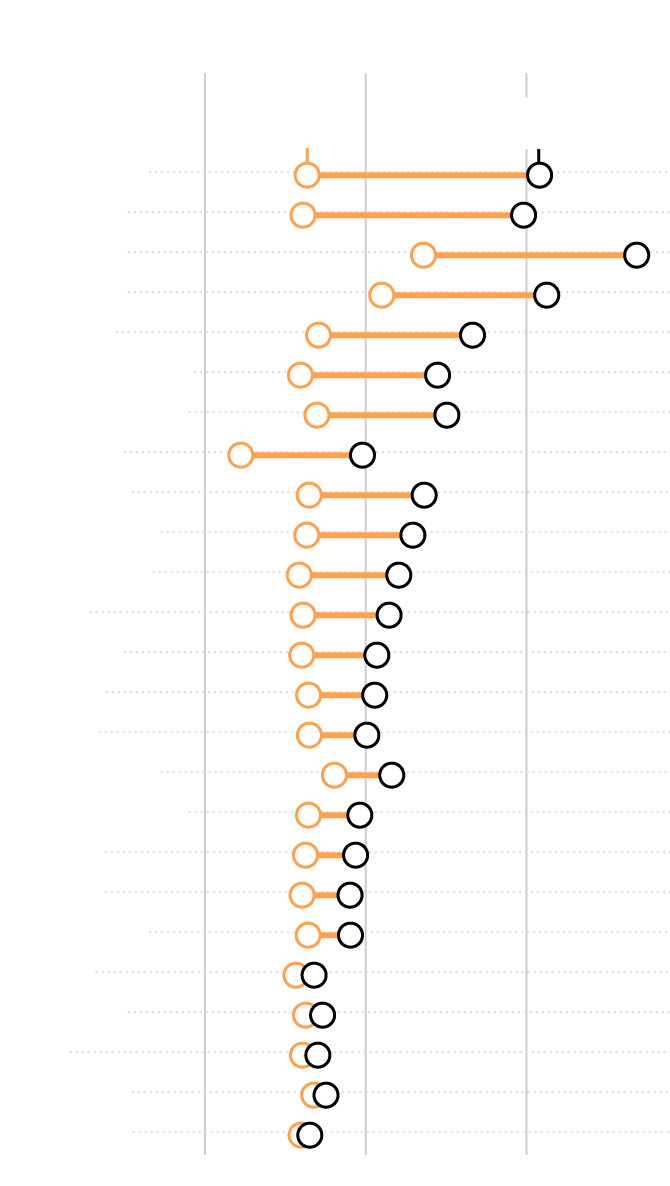

Our analysis shows that some states have received far more rental assistance than they need, while many others could run out within the next few months.

New York, for instance, allocated or spent more than 80 percent of its $2.4 billion in E.R.A. funds by mid-November. Gov. Kathy Hochul has repeatedly requested additional money, asking the Treasury Department to “re-examine its reallocation formula to prioritize high-tenant states like New York.” Yet when the Treasury reallocated some of the program’s funds this winter, it gave an additional $27 million to New York — less than 3 percent of the amount that she had requested.

Renters in many of the underfunded states are already in a precarious position, according to our Covid-19 Community Vulnerability Index, which rates states and counties based on their residents’ access to health care, affordable housing, transportation, child care and employment. Out of the $7.5 billion in additional funding that we believe would ensure renters’ needs are met nationwide, $5 billion is missing in states that we deem highly vulnerable.

What’s worse, the Treasury Department has started reallocating funds away from states and local governments that have been slower to spend the money that was originally allocated to them.

On its face, reallocating E.R.A. funding makes sense: If money isn’t being spent, it probably isn’t needed. But like the initial allocation formula, the Treasury’s reallocation process ignores on-the-ground conditions in states where renters have struggled with the application process.

The Treasury has an opportunity to make the rental assistance program smarter by reworking its reallocation formula to account for differences across states that our barometer identifies. The reallocation process shouldn’t punish renters who live in areas that are harder to reach or have higher housing costs or whose E.R.A. programs struggled to get off the ground.

After the national eviction moratorium ended in August, eviction filings began to tick up, and many state-level renter protections have fallen off the books. The Treasury must act now to prevent a potential wave of evictions in states where renters are struggling the most.

Sema K. Sgaier is a co-founder and the chief executive of Surgo Ventures and an affiliate assistant professor at the University of Washington. Staci Sutermaster is an associate researcher at Surgo Ventures.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.