What happened in a Rockville, Maryland, high school this January was a scene all too familiar for police officers across the US. An altercation between two boys ended with a shot ringing out, and a 15-year-old left bleeding on a bathroom floor.

What witnesses to the crime did next, however, shocked even Betsy Brantner Smith, a nearly three-decade law enforcement veteran and spokesperson for the National Police Association.

“The students started tweeting about it,” she said. “That’s just, unfortunately, the era we live in.”

Montgomery County police confirmed that fellow students tweeted about a shooting taking place, along with information about the victim and the shooter.

What they didn’t do was call for police or for help. The wounded boy was only found later.

The era that Ms Brantner Smith is referring to is one in which taking out a mobile phone has become almost a reflex, even when witnessing a crime.

Sometimes bystanders take photos or film, and sometimes they take to social media.

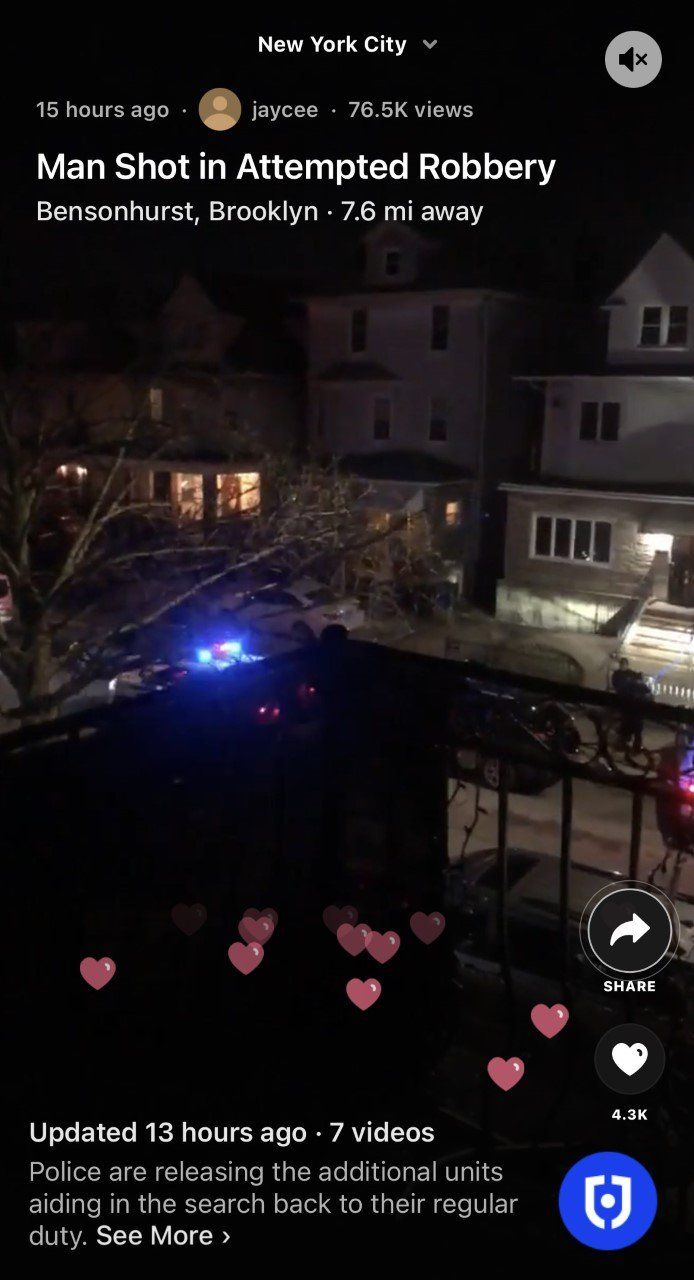

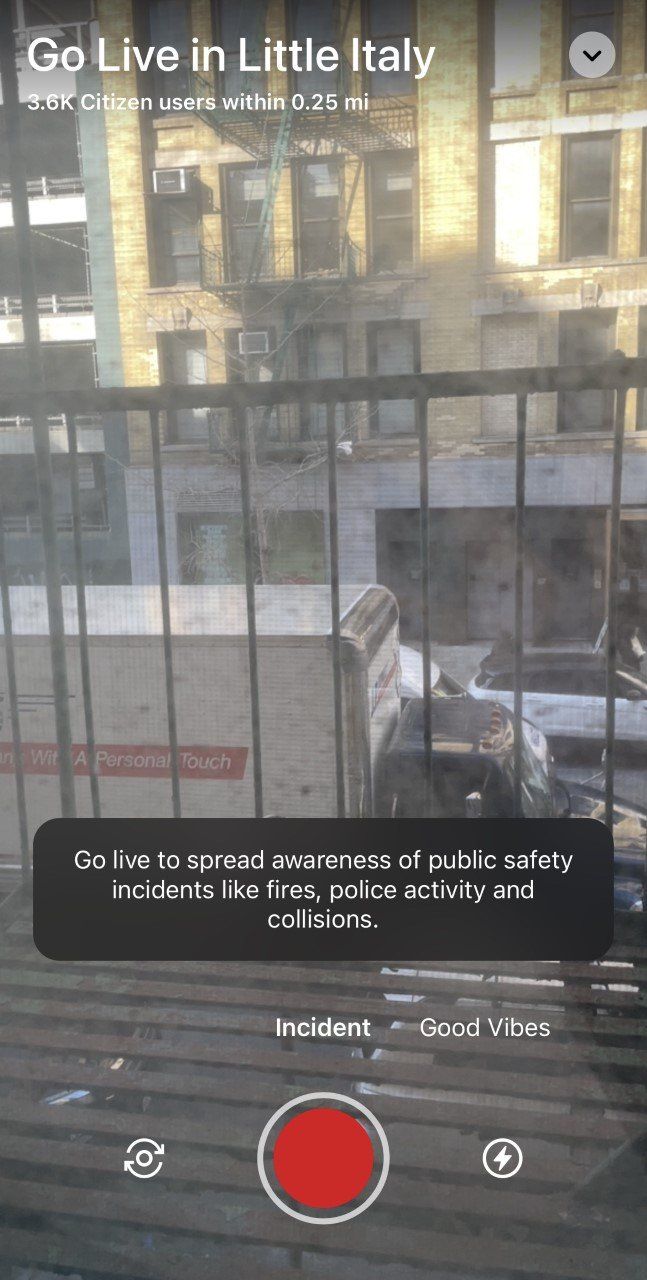

In recent years, commercial phone apps have emerged encouraging bystanders to report crime to these platforms.

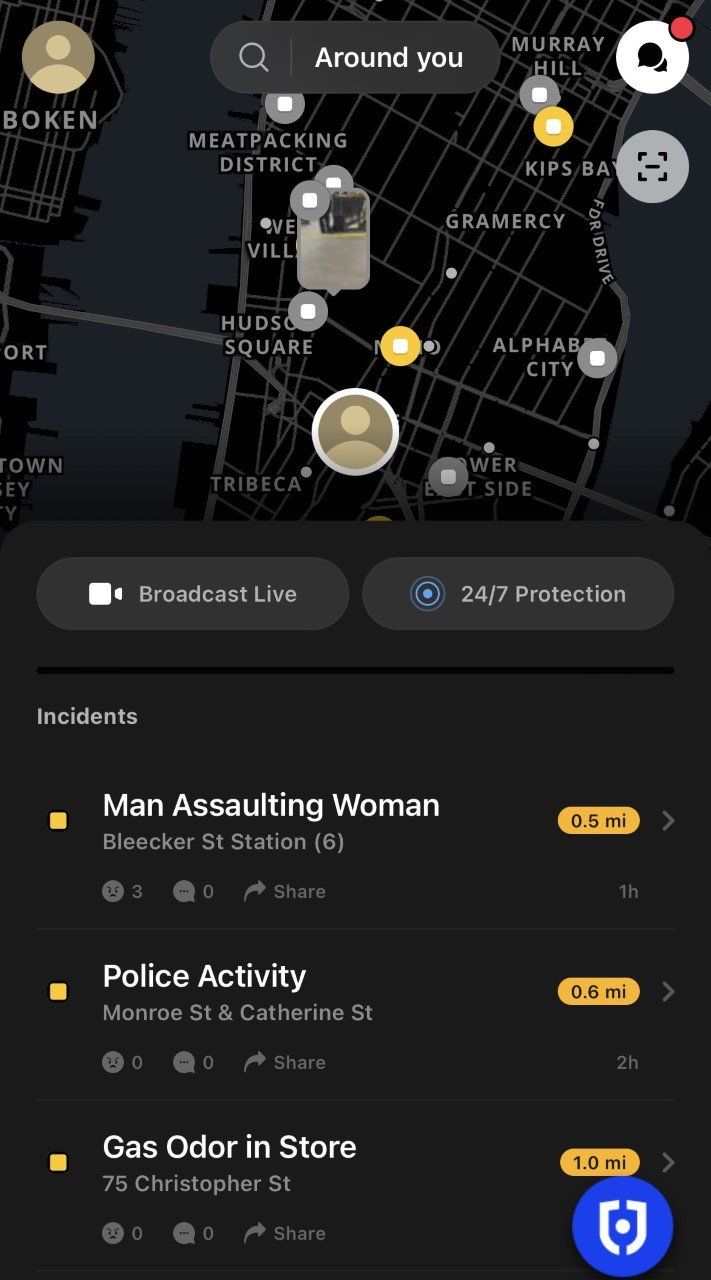

The most popular of these “public safety” apps, Citizen, has over nine million users. Founded in 2016 under the name ‘Vigilante’, it uses information from police scanners and social media to alert users to nearby emergencies.

The app’s core philosophy is that access to information can protect the public from danger. It also includes a “record” function that allows users to take video and shoot live footage from a scene.

Citizen is not the only such app in the US, though it is perhaps the best known.

Other examples include Neighbors by Ring – an Amazon subsidiary – which allows users to share photos and video clips from ‘smart’ doorbells and surveillance cameras and discuss crimes with residents. Nextdoor, a social networking service, is designed to help neighbours connect and share local news and events, often with a focus on crime.

The rise of these and similar applications in the US – what some experts have dubbed ‘crowd-sourced suspicion apps’ – combined with the ubiquitous use of mobile phone cameras have prompted fears of a new, digitally charged “bystander effect”.

When the impetus to take images or report to apps is so prevalent, will witnesses be filming instead of helping or calling police for aid?

Bystander effect, also known as bystander apathy, is a theory that the presence of others discourages onlookers from intervening in emergencies.

The term dates to the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese, a 28-year-old woman stabbed to death in New York City. Initial reports – which were later disproven – suggested that dozens of people witnessed the murder but didn’t intervene or call police.

While more recent research suggests that bystanders do, in fact, help in most instances, public concern remains. A high-profile example last autumn starkly highlighted the issue when fellow commuters in Philadelphia failed to report a rape on a train as it took place before them.

In most US states, bystanders are under no legal obligation to intervene or help unless they have a “specific” duty to do so, such as if they are parents, teachers, caretakers, or police.

There is concern that bystanders could seek “notoriety” from filming something and uploading incidents, said Tamara Rice Lave, a law professor at the University of Miami.

“People want to go viral, and that competes with their duty – whether it’s a legal duty or not – but a moral duty to their fellow citizens,” she said.

Research into the psychology of people filming a crime remains scant – although some psychologists say that they believe that it may be motivated by a desire to help, without having to physically intervene or act.

“We don’t have a lot of data, but the hypothesis is that it is a way of people doing something,” said Elizabeth Jellico, a clinic psychologist and sexual violence prevention researcher and professor at New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“I think people feel that by filming it, they’re kind of documenting [crimes] and in a way that they are contributing,” Prof Jeglic added. “It does help, sometimes, in the prosecution of crimes. However, it doesn’t, in the immediate moment, help the person who is being assaulted.”

Critics of the Citizen app have accused it of causing “paranoia” and altering perceptions about crime.

“It’s pretending to provide public safety, but in reality, it’s just providing a paranoid spectacle,” said Angel Diaz, a law lecturer at the University of California – Los Angeles. “We shouldn’t be relying on a private company to supplement people’s safety.”

“It made me feel like the city is much more dangerous than it is, as the amount of crime reported is quite alarming,” said Nadia Tarasova, a 22-year-old Citizen user in Chicago.

Ms Tarasova said she was often overwhelmed by as many as 30 notifications a day.

“They report on small things such as a dumpster fire, or they exaggerate things. They’ll say it’s a crowd protesting when it’s just 10 kids standing in a park talking to their teacher.”

Ms Tarasova – and millions of other users – do see benefits to the technology. In her case, she believes it helps her make informed decisions about what areas are safe to be in alone and which aren’t.

“I like being aware of my surroundings, especially as a woman,” she said.

Responding to questions from the BBC, a Citizen spokesperson said the company sees its technology as “complementary” to 911.

“Citizen is not a substitute for law enforcement,” the spokesperson said. “If a user sees a crime being committed, they should contact local authorities.”

Some scholars have also expressed concern that bystanders filming and uploading the content online may lead to racial profiling.

“Actually, my concern is not about the bystander effect,” said Lauren Briges, a PhD candidate at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s about mob justice.”

“They are almost changing the definition of the bystander in a sense – that through the action of live streaming, or through the action of capture and recording, that it’s a form of intervention,” she added. “Except for the fact it’s heavily racially biased.”

Citizen’s spokesperson said that such fears are a “mischaracterisation of [the app’s] core functionality” to notify people when potentially hazardous situations are taking place nearby.

The company said it has taken steps to reduce the number of notifications and improve their relevancy and frequency to address criticism of the app’s impact on perceptions of crime.

“We also avoid publicising vague suspect or suspicious person descriptions,” the spokesperson said.

The number of people filming and using crime-reporting apps will only increase in the future, particularly as young, tech-savvy digital natives begin to form a larger segment of the population.

It will be important to teach bystanders do more and act in the moment, such as by calling 911 or safely attempting to intervene, and not just film, said Prof Jeglic. She compared it to the sexual assault education provided in many high schools and universities across the country.

“I think that the younger that we teach students how to intervene, the more likely that they’ll practice these strategies and the more likely they are to intervene,” she said. “The more comfortable we are with a game plan before it happens in an emergency situation, the more likely we are to act on it instinctually.”

Others aren’t so sure.

Kevin McMunigal, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University and former federal prosecutor, said he believes that in the US approach – in which the law can’t mandate that people help – means in many cases, people may film instead.

“It seems very counterintuitive [to film] because it’s against one’s moral compass or what’s right and wrong,” he said. “But the US approach is very individualistic.

“It’s the same sort of ‘rights’ thing that you see with people saying they don’t want a vaccine or to wear a mask. People don’t want the law telling them when they should be good Samaritans.

“It’s amazing to me that it’s such a prevalent view in the US, but it is.”