Each tasting is a chance to be rendered wide-eyed and wordless.

As a kid, I was prone to nosebleeds. My parents, citing traditional Chinese medicine, blamed all the fruits I ate that gave me “excessive heat” — especially the lychees, my favorite. It didn’t stop me from gobbling them down by the dozens, pretending each was a succulent eyeball. After we left China and settled in a suburb of Quebec City, lychees became harder to find, and thus an infrequent treat. When we would drive to Montreal’s Chinatown to shop for groceries, I’d scan all the produce flats, looking for my red jewels.

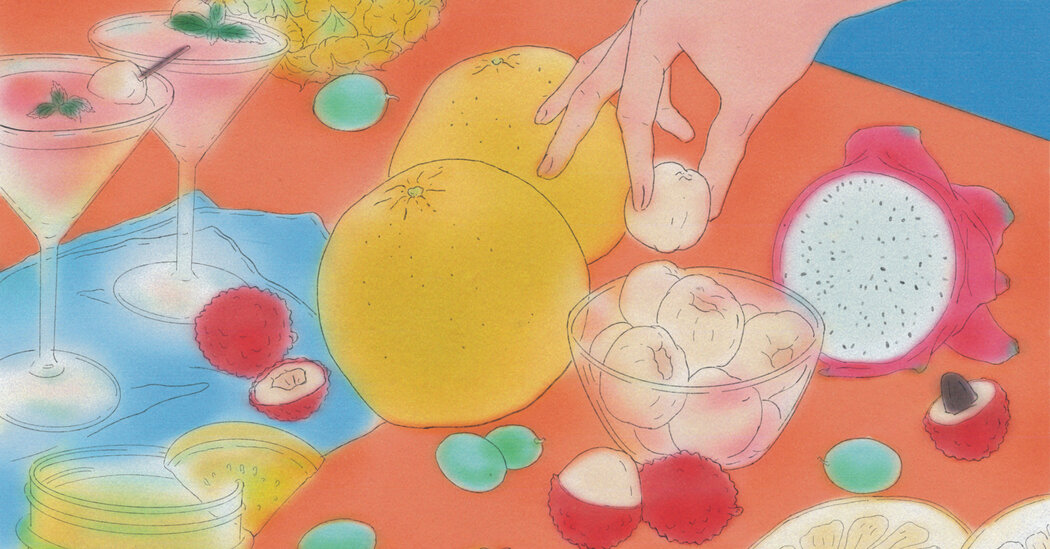

As I’ve grown older, my fixation on exotic fruit has intensified — the weirder, the better. The reality of being an armchair pomologist in Canada is that most of our fresh fruit is imported, especially during the colder months. The consequent silver lining is that almost everything in my local stores qualifies as exotic and interesting. Maybe it’s a finger-shaped lime with juice vesicles that look like caviar; maybe it’s a ham-hued pineapple, engineered by Del Monte to be Instagrammed. It doesn’t matter if a fruit is natural or genetically modified, beautiful or misshapen; I am an equal-opportunity sampler.

Trying a new fruit expands my understanding of the world and enriches my experience within it. Just when I think I have a solid grasp on the spectrum of natural aromas, a fruit like the lulo (a nightshade that resembles a tomato and is known in Spanish as a “little orange” but tastes like neither) appears at my favorite cheese boutique and undermines the whole system. I bought a couple to make cocktails with — a common usage for the fruit in its native South America — and marveled at its remarkable redolence, which perfumed my whole kitchen for days. Part pineapple limeade, part rhubarb-flavored gummy, it’s a scent so neon I’d rather believe it was plucked from a food scientist’s imagination than accept that this unicorn fruit just happens to grow in some people’s backyards.

Or take the Oro Blanco (“white gold”) grapefruit, a product of the Citrus Experiment Station at the University of California, Riverside. Developed as a hybrid between a pomelo and a grapefruit, the Oro Blanco inherits the juiciness of grapefruit without that bitter edge, and the floral sweetness of pomelo without its thick, woolly pith. Encountering an Oro Blanco for the first time made me marvel at the ingenuity of the human species. (And, in equal measure, our hubris.) The one I sampled was ambrosial and diametrically opposed to the anemic citruses I’m used to, which tend to be picked before their time and left to ripen slowly under grocery-store fluorescents. It had a sweetness I wasn’t sure I’d earned.

The soursop splits like flesh but spoons like custard.

There’s a line in a Jack Gilbert poem that has inhabited a nook in my brain since I was a teenager. “What lasted is what the soul ate,” he wrote in “The Spirit and the Soul.” “The way a child knows the world by putting it/part by part into his mouth.” I think of these lines often when I prepare to eat a new fruit. Each tasting is a chance to be reunited with my inner child, to be rendered wide-eyed and wordless as I get to know it, part by part. Those tasked with naming these fruits appear to be equally under a spell, producing monikers as simplistic as they are charming. Cotton candy grapes. Ice cream bean. Dragonfruit. Tell me these names aren’t the work of a captivated 6-year-old.

Some astronauts report experiencing the “overview effect,” a sense of mental clarity and connectedness to humankind that overcomes them when they look down at Earth from space. I feel that on a cellular level when I pick up a mangosteen, a celestial-purple orb with a flower-stem hat. It looks as if it were conceived for a Miyazaki film, its proportions so cutesy that it demands to be anthropomorphized. Inside are pillowy white segments, oneiric in texture and taste, with notes of pineapple, strawberry, lychee and your most carefree memory of childhood. The experience is no less expansive than seeing the ocean or hearing a Chopin nocturne for the first time. You catch yourself wondering what else this world has been hiding, what staggering beauty it’s capable of.

Most fruits I try only a couple of times, because I am an incorrigible neophile. But there’s one I keep returning to: the soursop, a member of the Annonaceae family and relative of the cherimoya and pawpaw. From the outside, it looks like a spiny reptile curled into itself or some sort of prehistoric football. It splits like flesh — with a hand on each half you feel violent, as though you’re tearing through ligaments — but spoons like custard. At optimal ripeness, the soursop tastes like the platonic ideal of tropical fruit: a beguiling combination of citrus, banana, pineapple, strawberry and papaya. Wait just a day too long, though, and it starts to brown, emitting a pungency that registers more as feet than fruit.

This rapid decaying comforts me, inexplicably. It’s not as if we’re short on reminders of mortality these days. Yet watching a beloved fruit transform from unripe starches to mushy pulp feels like being witness to an act of living. The plant, after all, sacrifices fruit in hopes of disseminating its seed; life was always the point. A looming expiration date is only encouragement to devour these tangible joys as they come and not attempt their preservation. We, too, will soon wake up and find our bodies softened and bruised, smelling a little cheesy. Will we have let our sweetest days go to waste?

Tracy Wan is a writer and brand strategist in Toronto.