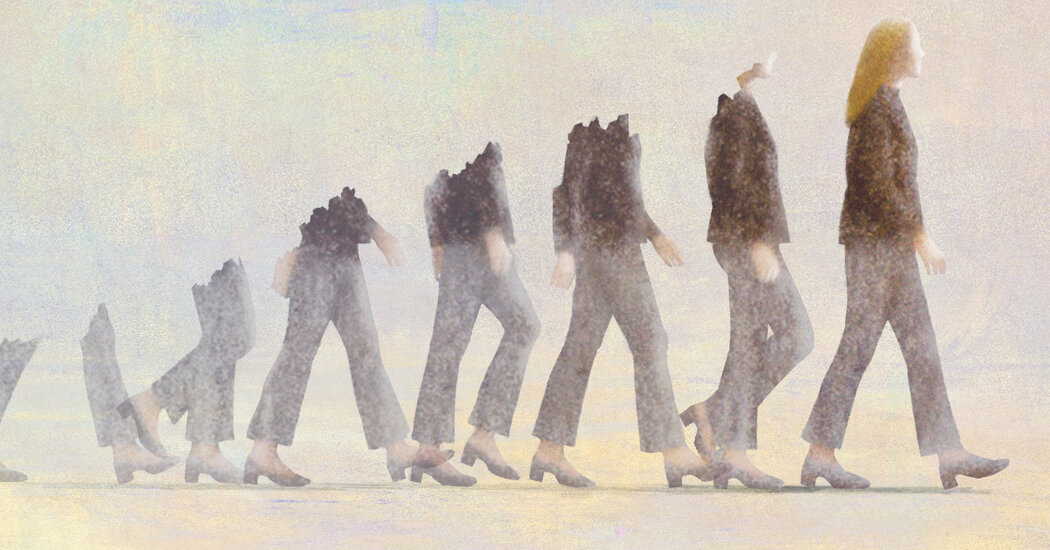

This winter, for the third time in my life, I began learning how to do something I was sure I’d mastered 60 years ago: how to walk.

I have photographic evidence of the first go-round: my shy, dignified father, drenched in 1950s suburban sunshine, trying to show a 1-year-old me the ropes.

Forty years later, when I came out as trans, I got a different tutorial on how I was supposed to walk. Swing your arms, one friend told me. Swivel your hips. “Women don’t swagger,” someone else told me. “We glide.”

Like a lot of the advice I got early on about how to be a woman in the world, most of this turned out to be poppycock. (I was also told that I could never order baby back ribs in a restaurant again because, according to this expert, “Women don’t eat baby back ribs” — a rule I was relieved to learn was false.)

Still, over time I discovered there is a distinction between walking in the world as male and as female, but it doesn’t have anything to do with swaggering or gliding. The real difference is that now, when I’m walking home alone at night and I hear a pair of footsteps behind me, I feel a sense of vulnerability I never felt before transition. That’s what it actually means to walk as a woman: to constantly be on guard.

There are a lot of different ways of being female in this world and a lot of different ways of walking. But all the women I know have this one thing in common. When we walk alone, we’re always a little bit careful. Because we have to be.

I found my footing, and for 20 years, I have been both joyful and wary. At least I had my equilibrium. Then I lost it again.

For many months, I simply thought I had lost my sense of balance. But recently I discovered the root of the problem: My gait is, to put it gently, curious. And not only do I walk funny; I stand funny, too, balancing on the sides of my fallen arches instead of on my heels and toes. As a result, apparently, the muscles in my shins have had to work overtime to keep me standing upright.

To solve the problem, I’ve been working with a gait specialist, a kind of physical therapist I did not previously know existed. It’s early yet, but I have slowly been learning to walk differently. I have begun to feel better, too: I have less pain and, more important, more confidence. In fact, it may be my lack of confidence, my sense of uncertainty in the world, that brought about my lack of balance in the first place.

My problem seems to have started in the summer of 2016. Which was just a few months after I lost much of my hearing.

It never occurred to me that there was any connection between losing my hearing and losing my balance. “But of course there’s a connection,” my doctor told me. “You’ve lost your sense of certainty in the world. Your gait and your stance are off because, with the change in your hearing, you literally don’t know where you are in space.”

That was also the year I expected to see the election of the first female president, only to witness the Oval Office occupied by a man who unleashed a dark font of vitriol aimed at people like me: feminists, progressives, L.G.B.T.Q. individuals, the disabled. Sadly, the election of Joe Biden failed to illuminate that darkness. Abortion rights nationally are probably about to be crushed, and one whole party now seems ever more determined to end American democracy as we’ve known it. On Thursday the governor of Texas directed state agencies to investigate categorized gender-affirming care for trans youths as “child abuse.”

I’m not the only one who’s lost her sense of balance in this world.

But if we’ve lost our sense of equilibrium, I know from experience it’s not impossible to get it back.

In mid-February I walked, for the first time in two years, the five blocks from my apartment to in-person worship at New York’s Riverside Church, a place with a long history of fighting social injustice and of working for peace. I sat down in my old pew, No. 523. Most of the people who I used to see before the pandemic were gone, but there were a few familiar faces; we shared the peace by bumping elbows. There at the pulpit was the Rev. Michael Livingston, whose sermon that day was about forgiveness — an idea he wove carefully around the forgiveness that Joseph showed his brothers in Genesis 45, when they appeared before him in Egypt, years after they sold him into slavery. Joseph, Mr. Livingston told the congregants, might have sought revenge. Instead, Joseph chose compassion, standing on the side of forgiveness.

“That’s what we have to do: stand. When your enemies surround you, stand,” said Mr. Livingston. “When all seems lost, stand.”

Using classic Gospel anaphora, he recounted examples of people fighting injustice and showing forgiveness, and then he repeated that word: Stand!

He implored us, “Like Harriet did against the evil institution of slavery planted on the American plantation, nurtured later in Jim Crow and mass incarceration, voter suppression today, stand! Like Thurgood Marshall, like Ida B. Wells risking her life to say no to the lynching of Black people in the late 19th century, stand! Like Rosa Parks when she sat down on that bus, stand!” He went on: “For the rights of our L.G.B.T.Q. siblings when they’re denied over and over and over again, these relentless attempts to keep people from being who they are, who God created us to be, stand!”

The sermon offered a brief inventory of all the injustice around us and all the work — and forgiveness — that still lies ahead.

It wasn’t easy. But at his urging, I did the thing I thought I had mastered years ago, the thing that I have had to relearn in order to regain my lost equilibrium, in order to feel safe in the world once more. I did it in order to do the work I need to do, in order to take the next step forward.

I stood.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.