The actor and writer recounts his life, from Bensonhurst upbringing to Broadway smashes, in a raw, funny and fabulous memoir.

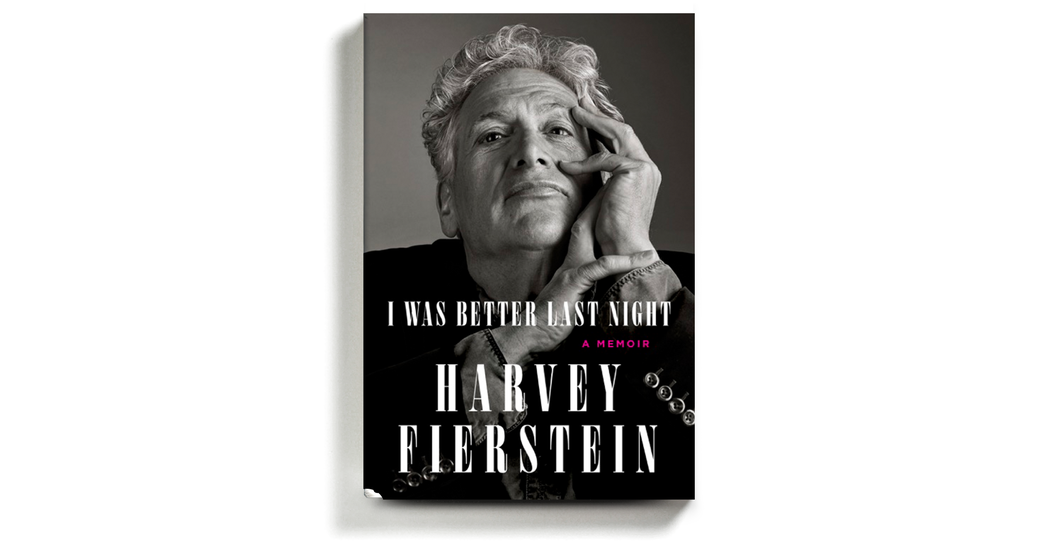

I WAS BETTER LAST NIGHT

A Memoir

By Harvey Fierstein

Illustrated. 383 pages. Alfred A. Knopf. $30.

The actor, writer and consummate New Yawker Harvey Fierstein is assuredly a man of many talents. Who knew needlework was one of them?

In his new memoir, “I Was Better Last Night” — the title refers to a theater performer’s perennial lament, but with aptly sexualized undertones — Fierstein writes of his “passion for crochet.” In the lean years before his play “Torch Song Trilogy” hit Manhattan like a ton of graffitied bricks in 1981, he embroidered clothes for chic boutiques and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Detoxing from Southern Comfort, his “longest love affair,” Fierstein took up quilting, hoping eventually to contribute to the famous AIDS memorial project, but also recognizing the hobby’s general practicality: “Quilts have two sides, doubling the chance you’ll find something you can live with.”

Intentionally or not, “I Was Better Last Night” is very quilt-like. Fierstein shares his life less in conventional chapters than in colorful patches: 59 of them, stitched together with photos and a plush index. The sum of this is warm and enveloping and indeed two-sided: One is a raw, cobwebby tale of anger, hurt, indignation and pain; flip it over and you get billowing ribbons of humor, gossip and fabulous, hot-pink success.

As with a treasured blankie, the frayed side is somehow more lovable. Fierstein writes of growing up with his older brother, Ronald, in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn, where “Jews cautiously befriended Italians, who guardedly befriended the Greeks.” He was one of several students named Harvey — the name’s trendiness being one of the “three greatest mistakes of the ’50s,” he jokes, along with Formica and thalidomide — but always stood out in a crowd. Enlarged tonsils made it hard to eat; removing them led to gorging and weight struggles. Overdeveloped secondary vocal cords were responsible for his distinctive growl. From a young age he wanted to dress up and make up and make believe, including as a mermaid, and wondered if he was a girl. Now he recognizes that he was a “7-year-old gender warrior.”

Blessed with a high I.Q., Fierstein skipped two grades and attended the High School of Art and Design in east Midtown, where there was a smoking terrace for students: “Hello, 1965!” When the author Anaïs Nin visited Fierstein’s English class, an elegant harbinger of what would be many encounters with the celebrated, he read her tarot cards. Undiagnosed dyslexia drew him to play scripts: sparer texts, meant to be spoken aloud. Unsurprisingly, some of the snappiest parts of this book are bits of remembered dialogue. (“You’re Madeline Kahn!” a ticket seller protested when the comedian, nearing 40, brandished an N.Y.U. ID and demanded a student discount to “Torch Song.” “With so much more to learn,” Kahn replied.)

Andy Warhol also figures. Little Harvey had admired the illustrations of footwear the artist did for Bloomingdale’s newspaper ads; while a sophomore at Pratt, where he made ceramics with genitals called Bad Boy Jugs, Fierstein got the part of an asthmatic lesbian maid wearing a red wig in “Andy Warhol’s Pork” at La MaMa, the temple of Off Off Broadway. He mingled with underground types at Max’s Kansas City (to pay the check, the Factory would send over a painting), though not without what became a trademark contrariness. “I could never catch what Candy Darling was talking about, and when I did, it wasn’t worth the effort,” he snipes about one member of Warhol’s entourage.

The author’s parents, despite their qualms about queerness, must have done something right, because throughout his life Fierstein (he pronounces it FIRE-stein, though his brother pronounces it FEER-stein) has been both fiery and fierce. “Jeez, but it was fun to be a teenager dropped in the middle of a revolution!” he writes of his early activism. Plays like “A Taste of Honey” and “The Boys in the Band” troubled him as documents of loneliness and self-loathing, and spurred him to write of gay life more affirmatively, more assertively.

It’s sobering to be reminded that as late as 1973, a male culture writer for The Village Voice was arrested for holding another man’s hand as they crossed a street in Greenwich Village. Fierstein’s interview with Barbara Walters in 1983, during the first successful run of “La Cage Aux Folles,” in which she “questioned me as if I were an interstellar alien” from Planet Homosexuality, was a thundering call for acceptance that still echoes today, on YouTube. “The norm,” he realized, “meant nothing but the majority.”

“I Was Better Last Night” gets to be more of an extended, eye-rubbing Tony acceptance speech after Fierstein hits the big time with “La Cage” and “Hairspray” and their various tours and revivals — or at least the medium time (Hollywood has never made proper use of him). Still, this man seems to roll around, constitutionally, in velvety darkness. Medical matters, including a suicide attempt in the mid-1990s, are handled with matter-of-fact frankness. When living “Cheetos-to-cheek,” he suffered terrible dental problems. Acting as Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof,” he got a hernia and had to manipulate his intestines back into place to go on. He had an aortic valve replacement, and offered the choice between pig, cow or manufactured, he wondered: “How serious could this be if it involved shopping?” (There are enough one-liners in “I Was Better Last Night” for a one-man show, and guess what, he’s available.)

The effect of AIDS on his community has left Fierstein — only spared, he surmises, because he grew bored with anonymous sex — burning with as much righteous rage as when he pointedly kissed a disease-phobic Ginger Rogers, a childhood idol, on the cheek backstage at “The Tonight Show.” “They’ve turned us into drug addicts,” he writes of antiviral medication manufacturers, “and managing us is a very profitable business.”

With a dramaturge’s expert timing, Fierstein saves the most difficult anecdote of his upbringing for near the end, like the classic 11 o’clock number in musical theater. A story about his mother’s reaction to his accidental coming-out, it’s a pin prick to the heart. Actually it makes the heart a pin cushion.